The Mystery of the Siberian Ice Maiden

A 2,500-Year-Old Mummy with Tattoos Turned Into a Battleground Between Tradition And Science

On September 27, 2003, a 7.3 magnitude earthquake struck Russia’s Altai region. Three hundred houses were damaged, and three lost their lives.

The people of Altai, where shamans still hold sway, were ready to attribute their misfortune to upsetting their ancestors. We can trace the source of their fears back a decade.

In the summer of 1993, archaeologists excavated close to the China-Russia border in Altai’s Ukok plateau. The site was known for the Pazyryk kurgan burials, first discovered in 1929 by M. P. Griaznov. Kurgans are mounds across Eurasia, from Siberia to the Black Sea, where high-status individuals were interred during the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age.

Natalia Polosmak, the project’s lead, was growing impatient. Her team dug for over two months to discover decaying meat and six frozen horses in the permafrost.

On July 19th, a jawbone appeared. Soon, they saw a shoulder with a beautiful blue tattoo. A mummy emerged from the permafrost.

The media called the mummy the “Siberian Ice Maiden,” and the name stuck. This incredible discovery excited scientists.

However, the locals viewed the excavation with suspicion. The dead shouldn’t have been disturbed. The mummy was studied and then toured the world. These acts were considered sacrilege by the people of Altai.

The Siberian Ice Maiden became a flashpoint between tradition and science. Archaeologists have long believed the mummy belonged to a culture distinct from the present-day Altai people. The locals challenge the assertions and suggest the “princess” of the Ukok plateau was part of their heritage.

But whose claims are valid?

Recent discoveries may help settle the debate about this mysterious mummy. Before we discuss why the find was controversial, let’s learn about the Siberian Ice Maiden.

Tattoos, cannabis, and cosmetics: The story of the Siberian Ice Maiden

The Siberian Ice Maiden is the name given to the mummy of a 25-year-old woman from the Pazyryk culture. This Scythian nomadic society flourished in Siberia, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia between the 6th and 3rd centuries BC.

Polosmak directed her team to melt the ice to remove the mummy from the permafrost.

As the archaeologists began melting the ice with buckets of boiling water, they discovered harnesses, saddle pieces, and a table where a meal of fatty mutton had been kept for 2500 years.

The meat was rotting, emitting a foul stench.

There were six horses. The marks of a pickaxe on their heads indicated that they had been executed, probably as part of a ritual sacrifice.

Then there was more ice.

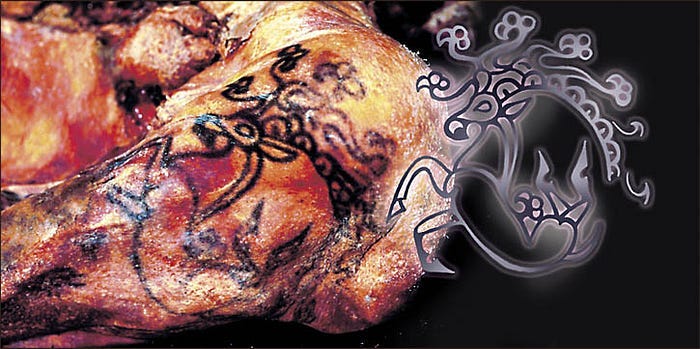

The archaeologists worked painstakingly to melt the remaining ice and finally found some sable fur. When they removed the fur, a shoulder appeared with a “brilliant blue tattoo of a magnificent griffin-like creature,” in Polosmak's words.

It was the body of a young woman around 25 to 28 years old. She became renowned as the Ukok Princess or Siberian Ice Maiden. Her tattoo depicted a beast, a mythological deer-like monster from the Eurasian Steppes. This creature, which has a beak, antlers, and a bent back, can also be found in other regional arts.

Polosmak’s team extracted the mummified body, which was in excellent condition. The archaeologists were unable to ascertain the cause of death because all her internal organs, including her brain, were removed.

But, two decades after her discovery, experts at the Russian Academy of Sciences have an explanation.

She died of breast cancer, most likely. According to the MRI scans, Dr. Andrey Letyagin believes she developed breast cancer in her early twenties. The asymmetry in the MR signals from the scan, according to Dr Letyagin, shows she had a tumor in her right breast.

The disease’s excruciating pain worsened over time, weakening her. She probably fell off a horse and fractured her bones shortly before her death. Her shoulder and collarbones were injured in the accident.

She was in pain and turned to cannabis for relief. Cannabis was discovered in her grave. High-ranking individuals of the Eurasian Steppe tribes used cannabis extensively, particularly for therapeutic purposes.

Dr. Polosmak's team reported that the Ice Maiden's skin was intact and embalmed with herbs, grasses, and wool. The horses were sacrificed and buried with the princess. They dressed her in a silk blouse and striped wool skirt. Because the highest-ranking members of nomadic civilizations wore silk, it is reasonable to infer she was a princess of some sort.

The Ice Maiden had a cosmetics bag on her left hip, showing that she was quite the fashionista of her era. Fragments of an eyeliner pencil made of vivianite, a type of iron phosphate that gives it a blue-green color, were also present. The archaeologists also unearthed a small plate containing coriander seeds, probably used for medicinal purposes or as seasoning.

But the biggest surprise?

She was bald.

Her hair was a wig consisting of two layers of female hair, and they shaved her head. On top of her wig was a felt spike with fifteen birds made of leather, each smaller than the last.

A wooden deer covered with gold foil was pinned to the front of the wig.

Understanding the findings and the culture

The Siberian Ice Maiden was almost certainly a part of the society’s elite. Members with positions of power could afford fancy apparel and cosmetics. Her lavish funeral with horses and a feast for the afterlife reflect her social status.

Though we don’t know who she was, speculations range from princess to priestess or priestess-queen. Another theory suggests she was a shaman. Typically, in nomadic Steppe cultures, shamans held positions of power.

The abundant grave goods show that her death was a significant loss for her community. Her burial for the afterlife was meticulously planned, with everything from eyeliner to cannabis medication provided.

According to Polosmak, tattoos are a symbol of beauty. Back then, like today, the goal was to appear as gorgeous as possible. Because the tattoo was visible, she placed it on the shoulder to appear attractive.

Other historians believe that tattoos marked elite status and connected them with warriors. Archaeologists have found graves of men and women with tattoos in the Pazyryk burials.

The Ice Maiden had tattoos on both arms and fingers, but the one on her left shoulder was preserved for the best. According to Polosmak, the visible shoulder tattoo resembles a griffin’s beak. Other tattoos included sheep and a snow leopard.

Because of the animal-style painting, archaeologists assume the princess was of Scythian heritage. They have discovered similar artwork in Russia, Central Asia, and Europe.

Recently, on Notes, I shared a fascinating deer-shaped mask used by horses from the Pazyryk culture.

The Pazyryk Culture thrived in the Altai Mountains, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia. It is associated with kurgans containing elaborate grave goods. Among the most remarkable finds is the Pazyryk carpet, dating to the 5th century BC.

The rug, thought to have been made in the Achaemenid Empire, is the world's oldest known carpet. Because of the permafrost, it is beautifully maintained, allowing us to study it meticulously and appreciate the precise craftsmanship involved in its creation.

The wool carpet contains 232 symmetrical knots per square inch. The center has a ribbon pattern, while the edges feature deer, boars, and warriors on horseback.

The Pazyryk people practiced nomadic pastoralism, but there is also evidence of farming. They most likely adopted agriculture from surrounding civilizations with whom they had contact.

It is largely known that the Pazyryks were Scythians. According to DNA investigations conducted by the Russian Academy of Sciences in 2004, the Ice Maiden was of European origin and shared few similarities with modern Altaians. The analysis was used to justify retaining the mummy in Novosibirsk, and archaeologists who refused to send over the remains to the Altai received official prizes.

But were the archaeologists honest? Or was it a case of scientific overreach based on limited evidence?

Let's examine the conflict between the two sides and how recent discoveries might help settle the argument.

Clash of ideas: Tradition vs Science

The Altai Republic is an autonomous republic in Russia. It borders Mongolia to the southeast, China to the south, and Kazakhstan to the southwest. The indigenous Altai people are a Turkic ethnic group that makes up about 37% of the state’s population.

The Siberian Ice Maiden was Scythian, with roots in southern Ukraine and Russia. According to author John Man, an expert on Steppe Empires, the Siberian Ice Maiden is as much an ancestor of modern-day Altaians as Native Americans of Manhattan are of modern-day New Yorkers.

Before discussing genetics, we should remember that the Steppe Empires were always multi-ethnic and differed from empires in the Near East, China, and Europe.

When we talk about the great empires of the Eurasian Steppes, such as the Huns, Göktürks, or Xiongnu, we are talking about a political entity, not an ethnic group. Their organization was distinct from the Roman, British, and Assyrian empires.

Hence, it’s not unnatural for people of the Eurasian Steppes to feel kinship to a person of a different ethnicity who lived on their land.

The Altai government has intervened since discovering the Siberian Ice Maiden and designated Ukok as a special protection zone. In 1998, UNESCO added Ukok to their list of World Heritage sites.

The Ice Maiden had become a rockstar by this point. She went on a world tour and was greeted with great excitement in Japan and Korea. But Altai’s residents were unhappy.

Rimma Erkinova, the director of the Altain Museum, said, “She should never have been dug up.” According to her, shamans are still influential in the region, and if you disturb the dead, they’ll capture the souls of the living.

It’s easy to dismiss her concerns from a scientific point of view. But we are emotional beings. Symbols of the past are dear to us. To the Altaians, the Ice Maiden was one of their own, born on their land, and she continues to bless them, regardless of her genetics or history.

The Altaians' worst fears came true in September 2003. Ten years after the Ice Maiden was dug, a series of earthquakes hit the Altai Republic. Letters, petitions, and pleas from ordinary people and politicians blaming the earthquake on the removal of the Ice Maiden flowed in.

Auelkhan Dzhatkambaev, the head of the earthquake-affected district, made one of the most passionate requests. He wrote an open letter to the Altai government, blaming the earthquake on the excavations.

This passage from his letter captures the feelings of many Altaians.

Further retaining of the princess and the prince and, even more so, earning money through displaying their naked bodies is contrary to human values. This is not a superstition, neither is this whim- this is wisdom, which has arisen from the depth of centuries.

Recent research may support the Altai people's views. Though the Scythians originated from the Western Steppe Herder (WSH) group, by the Iron Age, the Pazyryk people were closer to East Eurasians, with substantial influence from ancient Siberian populations such as the Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) and Ancient North East Asians(ANA).

Simply put, the Paryzyk people were more similar to Paleosiberian populations than European ones. Modern Uralic and Siberian populations, such as the Yukaghir, Mansi, Nganasan, and Khanty, have the most genetic similarities to the Paryzyk people.

Earlier this month, I discussed one of the most significant discoveries of 2024: the Siberian roots of Scythian culture.

Bronze belt decorations with animal designs, horse-riding gear, and arrowheads that echo the classic Scythian style were discovered in the Tunnung burial site, which predates equivalent Scythian artifacts found west.

Siberians may have migrated westward, intermingled, and influenced Scythian culture.

The people of Altai are not motivated by emotions or blind beliefs. There could be a compelling scientific rationale for why they sense a connection with the Siberian Ice Maiden.

In August 2012, when the Gorno-Altaisk Museum had proper facilities, the Russian authorities handed the Ice Maiden to the Altai people.

She had finally returned home.

The authorities declared the Ukok plateau off-limits for archaeologists, much to the dismay of the scientific community. However, recent discoveries could help us.

We cannot find direct answers since further research on her body is prohibited. But findings such as those at the Tunnung burial site help us better understand the Scytho-Siberian world, which the Ukok princess represented.

Do you love exploring the mysteries of lost civilizations and the rich cultures of the ancient world and Middle Ages? Share this story with friends and family, and don’t forget to subscribe to this newsletter for more fascinating insights!

If this newsletter sparks your curiosity, consider upgrading to a paid membership to support its growth. As a paid subscriber, you’ll unlock exclusive perks, including:

Early access to The Weekly Jarlig, your go-to source for the latest breakthroughs in history and archaeology.

Premium content reserved for our insider community.

Full access to archived content.

References

Polosmak, Natalia (October 1994). A Mummy Unearthed from the Pastures of Heaven National Geographic: 80–103.

Iconic 2,500 year old Siberian princess ‘died from breast cancer’, reveals MRI scan. Siberian Times.

Man, John (2017) The Amazons: The Real Warrior Women of the Ancient World.

Unterländer, M., Palstra, F., Lazaridis, I., Pilipenko, A., Hofmanová, Z., Groß, M., Sell, C., Blöcher, J., Kirsanow, K., Rohland, N., Rieger, B., Kaiser, E., Schier, W., Pozdniakov, D., Khokhlov, A., Georges, M., Wilde, S., Powell, A., Heyer, E., . . . Burger, J. (2017). Ancestry and demography and descendants of Iron Age nomads of the Eurasian Steppe. Nature Communications, 8(1).

Man, John (2019), Empire of Horses: The First Nomadic Civilization and the Making of China.

Sadykov, T., Blochin, J., Taylor, W., Fomicheva, D., Kasparov, A., Khavrin, S., … Caspari, G. (2024). A spectral cavalcade: Early Iron Age horse sacrifice at a royal tomb in southern Siberia. Antiquity, 98(402), 1538–1557. doi:10.15184/aqy.2024.145

Beautifully written, and well researched.

This mixed topic of history, genetics, and culture, hits all the right notes for me.

I agree with the Altai on the belief that they were wronged by the desecration of this grave.

Just imagine that one of the past popes bodies was taken from Italy, then the thief says that because the Pope wasn't from Africa the Middle East, or the Saudi peninsula that he couldn't be a Catholic. Because Catholicism comes from that area, and the Popes genetics say that he was an Anglo Saxon Englishman.

They are conflating religion and culture, with race, then using that obviously obscure difference to keep the body of a sacred individual. Period.

Just imagine that someone from a European Pagan background did this to a Pope's resting place and body.

Modern culture, first polarized by monotheism and then removed from all connection by science cannot understand a perspective that includes the deceased as an active force in existence.

Possibly the closest the modern mind ever gets to this is through fantasies like movies.

Yet the veneration and respect of ancestors has close resemblance with an approach to the planet that does not seek to destroy it.

For those who have not had it drilled out of them, communication with the dead is a very real thing. One can hope that the harmony of place has been returned, and those forces that were disturbed have returned to eternal flow.