Top 10 Historical Discoveries of 2024

Exploring the top finds that redefined our past

Hey, history lovers!

Ready for a time-traveling adventure?

2024 was a year of incredible historical discoveries that blew my mind. I’ve compiled a list of the year’s top ten historical discoveries that stood out, not as a ranking but as a reflection of what I found most impactful.

This isn't a race to the top but a recognition of the findings that most resonated with me, the ones that changed my understanding of the past.

Disclaimer: I'm biased.

Obviously!

The list is subjective. These discoveries had the most significant impact, whether they blew up existing theories, opened up new avenues of research, or left me utterly amazed.

What makes a discovery impactful?

It's not about uncovering new facts but about the questions it sparks.

How does a finding change our perspective on the past? Does it connect seemingly disparate cultures? Does it challenge our assumptions about how the world evolved?

So, prepare to be surprised, challenged, and maybe even slightly bewildered. And while you read, I encourage you to reflect: What discoveries would YOU have included?

Let’s dive in!

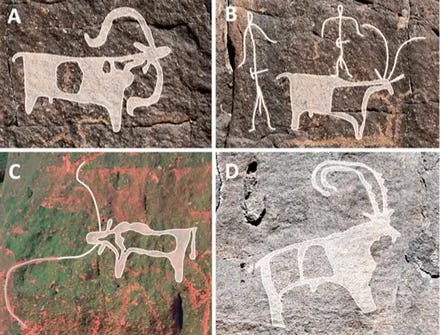

Petroglyphs Discovered Alongside Dinosaur Tracks in Brazil

Dinomania isn’t new. Our ancestors were as fascinated with these creatures as we are.

Archaeologists in Paraíba, Brazil, found petroglyphs near 100 million-year-old dinosaur footprints. These petroglyphs weren't carved over the footprints, suggesting deliberate avoidance.

It is unclear why they left the footprints untouched. Did the ancient people of Brazil revere dinosaurs as we do today?

In a study published in Scientific Reports, researchers Troiano, dos Santos, Aureliano, and Ghilardi noted the petroglyphs didn't damage the footprints. They found similar petroglyphs nearby, dating between 2,620 and 9,400 years old. These were found at the Serrote do Letreiro Site in Vale dos Dinossauros, alongside dinosaur footprints, including those of theropods and sauropods.

Although the creators likely didn't know about dinosaurs, they may have thought the footprints belonged to Rhea, a large flightless bird, or Notiomastodon platensis, a relative of the modern elephant. Similar cases of rock art near dinosaur footprints exist worldwide, but none show such a close connection as in Serrote do Letreiro.

The study suggests a symbolic link between human art and the fossil record.

What do you think? Did ancient people view dinosaurs as mythical creatures?

Evidence of Cities Found in Amazon Rainforests

Archaeologists using LIDAR technology have made a stunning find in Ecuador’s Upano Valley: a dense network of interconnected settlements going back at least 2500 years, making it the earliest known evidence of urbanization in the Amazon rainforests.

The LIDAR scan, funded by Ecuador’s National Institute for Cultural Heritage in 2015, uncovered hidden settlements beneath the forest canopy, defying the previously held belief that hunter-gatherers sparsely populated the ancient Amazon.

Led by Stéphen Rostain of the CNRS, France’s national research agency, the team discovered huge communities like Sangay and Kilamope, which included orderly mounds, ceramics, and ceremonial structures.

Radiocarbon dating places the Upano sites between 500 BC and 600 AD, more than a millennium before other Amazonian communities. LIDAR revealed links between sites, identifying five large and ten smaller ones spread over 300 square kilometers, highlighting urbanism, agricultural fields, and road networks.

The archeologists found each site densely packed with religious and residential buildings. The Amazonians built their cities on rectangular platforms after flattening the hilltops.

This astonishing engineering feat calls into question several long-held beliefs about Amazonian societies that have been neglected in discussions regarding civilizations. The people weren’t foragers who subsisted on whatever the forests provided. They were skilled farmers who built roads, canals, and monuments.

This discovery builds on the 2022 LIDAR study, which uncovered a massive urban civilization spanning 4,500 square kilometers in Bolivia’s Amazon. We call this expansive community the Casarabe culture (Llanos de Mojos), and it lasted between 500 and 1400 AD.

While many details about these “cities” remain unknown, the discovery reshapes our ideas about urbanism in the Amazon rainforests.

Keep an eye on this one, folks, because it has the potential of becoming an all-timer!

Denisovans, an Extinct Human Species, Once Lived in Tibet

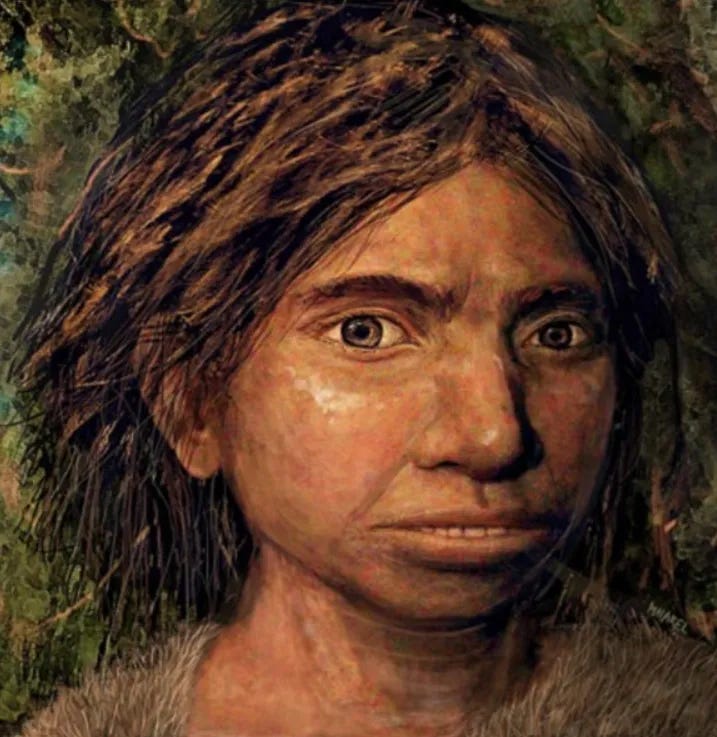

In this newsletter, we love talking about Neanderthals. But many other hominin species co-existed with our Homo Sapien ancestors.

Denisovans, a recently discovered hominin species related to Neanderthals and modern humans, remain a mystery. When they were first found in the Denisova cave of Siberia in 2008, scientists were skeptical if Denisovans were a new species.

Today, we know Denisovans interbred with our ancestors, leaving a genetic mark on some populations today. However, physical evidence for their existence has been scarce.

A recent study in Nature sheds new light on the presence of Denisovans in the Tibetan plateau. In 1980, a mandible and teeth (Xiahe mandible) were found in Tibet's Baishiya Karst Cave (BKC).

These remains, dated to at least 160,000 years old, were later identified as Denisovan. Mitochondrial DNA from BKC sediments confirmed Denisovan's presence from 167,000 to 40,000 years ago.

Excavations at BKC revealed thousands of animal bones, including those of wolves, yaks, snow leopards, and birds. By analyzing these remains, researchers discovered what Denisovans ate. Cut marks and other modifications on the bones indicated that Denisovan used tools to butcher meat and remove the skin from the animals.

In BKC, researchers found a Denisovan rib bone alongside the animal remains. Surprisingly, the rib bone is much younger than other Denisovan remains, dating back between 48,000 and 32,000 years old. This suggests there might have been an overlap between Denisovans and modern humans in the region.

They survived much more recently than we’d imagine!

Scientists analyzed proteins to confirm the rib bone's Denisovan origin. This discovery, along with previous findings of Denisovan DNA in the same cave, strengthens the evidence for their presence in Tibet.

World’s Oldest Cave Art Found in Indonesia

Long-time followers of this newsletter love prehistoric rock art. Any edition with news about prehistoric rock art wins the polls for the “favorite discovery of the month.” Well, now I got the cream of the crop for you.

The oldest known example of figurative cave art has been discovered on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. This painting, found in the caves of Karampuang Hill, depicts a wild pig and three human-like figures. It is at least 51,200 years old, making it the oldest known cave art by over 5,000 years.

The painting illustrates the early human capacity for creative thought and storytelling.

The research team, led by Indonesian rock art specialist Adhi Agus Oktaviana, believes this discovery indicates that narrative storytelling was integral to early human culture in Indonesia. The painting's detailed scene shows a pig with its mouth open and three human figures interacting, suggesting a story is being conveyed.

This finding challenges previous beliefs that representational art originated in Europe, highlighting the significant role of storytelling in early art.

Early artwork, such as geometric patterns in southern Africa and the oldest representational artwork in Borneo, support the notion that humans have been drawing for much longer than previously thought.

The scientists used a new dating method involving precise laser techniques, which allowed for a more accurate analysis of cave art.

The novel method could help unearth discoveries and push back the timeline of human artistic expression.

Humans Lived in Volcanic “Lava Tubes” in the Arabian Desert 7,000 Years Ago

Each year, adventurers from around the world travel to the Umm Jirsan lava tube system in Saudi Arabia to explore the mysterious underground tunnels carved by ancient lava flows. Spanning an impressive 5,000 feet, this geological wonder is in Harrat Khaybar, a gigantic volcanic field that last erupted in the seventh century.

Recent research reveals an incredible story. Prehistoric humans and their animals found shelter in these caverns for an astonishing 7,000 years during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Despite the harsh desert climate of northern Saudi Arabia, which made it difficult for ancient remains to survive, the cool, protected tunnels of Umm Jirsan acted as a natural time capsule, preserving traces of their lives.

Archaeologists unearthed human bones, animal fossils, stone tools, and captivating rock art depicting ancient life. Through careful analysis, they pieced together clues about these early inhabitants' diets and farming practices.

The study, led by researchers from Griffith University's Australian Research Center for Human Evolution (ARCHE), in partnership with international collaborators and Saudi Arabian organizations, highlights a previously hidden chapter of history in the region.

“This is really the first clear evidence of people occupying these caves. This site likely served as a crucial waypoint along pastoral routes, linking key oases and facilitating cultural exchange and trade”- Matthew Stewart, Researcher, ARCHE

The discoveries at Umm Jirsan are just the beginning. With thousands of volcanic caves scattered across Saudi Arabia, we can expect more such exciting finds in the future.

Neanderthals Were the First Fossil Collectors.

Have you wondered when we started collecting fossils? When did the first spark of curiosity ignite? It turns out the hobby of collecting fossils is older than we can imagine.

Archaeologists have found evidence of Neanderthals gathering objects with no practical use simply because they found them interesting or beautiful.

Carefully transported from Neanderthal times, researchers discovered an amazing collection of 15 marine fossils spanning millions of years at Prado Vargas Cave in Burgos, Spain. These fossils comprised gastropods and mollusks, such as extinct snails from shallow oceans. Except for one fossil, they seem not to have been employed as tools, implying they were gathered for another purpose.

Why did Neanderthals amass these relics?

Maybe they traded them, loved their forms or hues, or assigned symbolic value to support collective identification. Some even hypothesize children might have gathered them since modern youngsters are known to collect stuff for play.

Another theory is that the fossils were used for aesthetic purposes, perhaps as decorations.

Whatever the cause, this realization emphasizes the strong origins of the human impulse to gather and value objects and to be curious.

Now acknowledged as the first known fossil collectors, these Neanderthals from Prado Vargas Cave show that interest in the past wasn’t limited to humans.

Throughout this newsletter, I’ve emphasized how similar Neanderthals were to humans, and this discovery adds credence to the theory.

If you’re an amateur fossil collector, you’ve got more in common with the Neanderthals than you imagine!

Rare Bronze Age Shipwreck Found in the Mediterranean Sea

My first post on Substack was about the Uluburn shipwreck, a Bronze Age shipwreck found in the Mediterranean Sea.

I love reading about ancient shipwrecks and the cargo they held. Hence, you can imagine my delight when I learned another Bronze Age shipwreck was discovered in the Mediterranean this month.

In 2024, two ancient jars were lifted from the Mediterranean Sea. Covered in brown mud, they had spent over 3,200 years on the seafloor, a mile deep and 60 miles from land.

Their three-hour journey to the surface marked the first discovery of a Bronze Age shipwreck in deep waters off the coast of Israel. Archaeologists retrieved these Canaanite storage jars, part of a larger cargo, from off northern Israel’s coast in May.

Jacob Sharvit, director of marine archaeology at the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), noted this shipwreck is unique due to its deep-sea location. Most ships from the Late Bronze Age were found in shallow waters. This operation was a complex effort by the IAA and the gas company Energean.

The Canaanite jars, used around 2000 BC for Mediterranean trade, have a specific design to remain stable on ships. Expert Shelley Wachsmann explained their pointed or rounded bottoms prevent them from tipping over. The shape and design of these jars help date them between 1400 and 1200 BC.

This is the time that the Mediterranean is globalized. You’ve got lots of commerce, lots of diplomacy, and lots of interconnections- Eric Cline, Archaeologist, author of 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed

At the time, the Mediterranean was a hub of international trade and diplomacy, dominated by the Egyptian and Hittite empires. Merchant ships carried various goods between Greece, Cyprus, Anatolia, the Levant, and Egypt.

The discovery, like the one of the Uluburn shipwreck, highlights how interconnected the ancient Mediterranean world was.

Scythians Had Cultural Origins in Siberia

A new study suggests that the Scythians, legendary horse-riding warriors from Central Asia and Eastern Europe who lived between the 9th and 3rd centuries BC, trace some of their cultural roots to Siberia.

Archaeologist Gino Caspari and his Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology team examined artifacts at the Tunnug 1 burial site in Siberia, discovering links to later Scythian culture. They found bronze belt decorations with animal designs, horse-riding gear, and arrowheads that echo the classic Scythian style, suggesting that Siberian herders traveled westward over just a few centuries, bringing their customs with them.

The burial practices at Tunnug 1 even resemble the dramatic rituals described by the ancient historian Herodotus, who wrote of Scythian kings buried with sacrificed servants and horses—creating a haunting scene of “spectral riders” on the tomb’s surface. Though the site’s remains are partially weathered, traces of birch stakes found among bones match this eerie description. The team uncovered at least one human and 18 horse skeletons on the 2,800-year-old tomb, hinting at a ceremonial sacrifice for a leader or noble.

This isn’t the first time a strong Scythian link has been found with Siberia.

The Pazyryk culture, which thrived in the Altai region from the 6th to the 3rd centuries BC and influenced the later Xiongnu Empire, was a Scythian culture based in Siberia. However, the discovery at Tunnug shows that a cultural migration from the East to the West occurred, contrary to prior assumptions.

Neolithic Scandinavians Used Skinboats to Travel, Hunt, and Trade

During the Viking Age (793-1066), longboats were the preferred transportation choice for Scandinavians. But have you wondered how people in Northern Europe traveled in prehistoric times?

Dr. Mikael Fauvelle and his team propose that the Neolithic Pitted Ware Culture (PWC), a Scandinavian hunter-gatherer society active between 3500 and 2300 BCE, used skin boats for trade, travel, and hunting. The PWC is notable for continuing marine-based subsistence, focusing on seal hunting and fishing even as agriculture spread throughout Europe.

The distribution of tools, animals, and materials from distant regions supports evidence of their long-distance voyages across the Baltic Sea and nearby straits.

While dugout canoes were common during this period, their small size made them unsuitable for open-sea travel. Dr. Fauvelle suggests that skinboats, like those used by the Inuit, were more likely used by the PWC for maritime activities. These boats, made from seal hides stretched over bone or antler frames, would have been ideal for long-distance sea travel and open-water hunting.

Evidence supporting this theory includes potential boat frames in northern Germany and Sweden, rock art depicting seal hunting, boats resembling Umiak skin vessels, tools, and large amounts of seal oil essential for waterproofing skin boats. The frequent recovery of tools for hide processing further suggests that seals were used for food and boat construction.

Skinboats likely enabled the PWC's extensive maritime trade and hunting activities, a precursor to the Bronze Age's more advanced sewn plank boat technology.

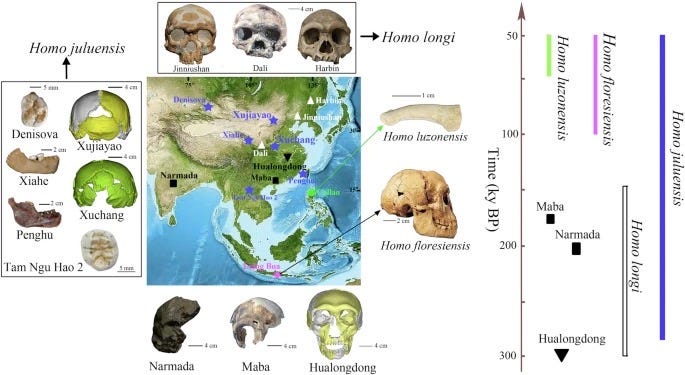

New Human Species Discovered

A team of scientists, led by Christopher J. Bae from the University of Hawai‘i and Xiujie Wu from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, have proposed a new species of ancient humans

called Homo juluensis. This species, whose name means “big head,” lived in eastern Asia between 300,000 and 50,000 years ago. The discovery sheds light on the rich diversity of human ancestors during the Middle and Late Pleistocene epochs.

The fossils found in northern and central China reveal a mix of traits. Homo juluensis had large skulls with thick bones like Neanderthals, yet also shared features with modern humans and Denisovans.

These humans were likely skilled toolmakers, hunters, and hide processors, helping them survive harsh environments. Their discovery challenges previous classifications, which often lumped fossils into broad groups like “archaic Homo sapiens.”

For years, scientists have struggled to sort out the “muddle in the Middle.” The term refers to the complicated and often perplexing picture of human evolution throughout the Middle Pleistocene epoch, approximately 700,000 to 300,000 years ago.

Different hominin species existed during this period, and their relationships with each other and modern humans are unclear.

Bae and Wu’s research suggests eastern Asia was home to at least four distinct human species: Homo floresiensis, Homo luzonensis, Homo longi, and Homo juluensis.

Interestingly, fossils from places like Tibet, Taiwan, and Laos, once thought to belong to Denisovans, might also be Homo juluensis due to similarities in their jaws and teeth. This discovery highlights how much we still have to learn about our ancient ancestors.

Do you enjoy tales from lost civilizations and cultures from the ancient world and the Middle Ages?

Share this story with your friends and family.

If you wish to support the newsletter, consider opting for a paid membership or buying me a coffee!

Very interesting compilation of these amazing discoveries.

This was a hum-dinger of a year for historical discoveries, but I'm curious as to how much more stuff we're going to find as the pace of technological innovation accelerates. the LIDAR/Amazon find is one obvious example, but it seems like generative AI can help a great deal more. I wonder if the pace picks up in 2025 and 2026! Very exciting times.