The Forgotten Origins of Indo-Chinese Cuisine

A tale of immigration and trade resulted in a cultural fusion

Growing up in a Bengali family in Calcutta (now known as Kolkata), Chinese food was a vital part of our lives. I would rush home from school, looking forward to a bowl of stir-fried noodles overflowing with soy sauce and a dash of chili sauce.

In the 1990s, there were few restaurant options, and Chinese food was reasonably priced. A trip to Chinatown for golden-fried prawns, sweet and sour chicken, and manchow soup was a ritual for us.

Having people over?

Not an issue.

Your local Chinese eatery, whose kitchen could be an actual hole-in-the-wall built illegally, had your back. Their food would be mouth-watering and impressive every time. For the city’s middle class, those dining establishments were lifelines.

Though Chinese cuisine is widespread throughout India, it has fused with the local cuisine in Bengal. Aside from the British and Portuguese, the Chinese had the most impact on Bengali culinary traditions.

In contrast to the Portuguese and the British, the Chinese immigrants to India in the late eighteenth century were modest laborers and traders seeking to profit from the global sugar boom.

To understand why dishes like chili chicken, Hunan chicken, garlic prawns, and lemon fish became staples in India, let us learn about a Chinese merchant who arrived in the eighteenth century at the Hooghly River delta in the Bay of Bengal.

Reminder: By choosing a paid membership (just $5 a month or $50 annually), you're helping amplify voices that history books too often overlook. Your support means these stories get the attention they deserve.

You’ll gain access to tons of members-only content👇

Full-length deep dives into untold stories, like this one: no paywalls, no cuts.

The entire archive of extraordinary tales from the Ice Age to the Fall of the Mongol Empire, the hottest archaeological finds, and the appetizing history of food.

Early access to special editions, be the first to dive in.

Join lively discussions in members-only posts and subscriber chats (there’s one at the end of the post!)

Failing Sugar Mills and Burgeoning Tanneries

If you ask someone on the streets of Calcutta what the Bengali term for sugar is, they will all say the same thing: chini.

Sugar was not referred to as chini in Indian languages. In Sanskrit, it is known as sharkara. In Bengali, it is called mishri, which is now used to refer to crystallized sugar.

So, how did chini become the accepted term for sugar? Also, why are we talking about sugar?

Sugar is vital to our story, as the first Chinese workers arrived on the coast of Bengal to work in the sugar industry. In the 1770s, a man with limited financial means but abundant optimism came to the Hooghly River Delta. His name was Tong Atchew (Anglicized from Yang Tai Chow).

The region was under the administration of the British East India Company and was a thriving commercial center. After a century of attempting to establish a foothold, the British seized control of the provinces of Bengal and Bihar from the Mughals by 1764 and were granted the right to collect taxes. The British hoped to profit from Europe’s growing demand for sugar and saw India as an alternative to Central America’s sugar-producing regions.

Following years of negotiations with the East India Company for trading rights, Atchew established Bengal’s first modern sugar factory in Acchipur, some 50 miles from Calcutta Airport. He began making refined sugar with a small crew of workers.

Chinese sugar was white and resembled the refined sugar of today, in stark contrast to the brown sugar prevalent in eighteenth-century India. For convenience, Indians began referring to the new sugar as chini, which translates to Chinese. Sugar quickly became synonymous with the Chinese-style refined white sugar.

Unfortunately, Atchew was not a successful entrepreneur. His factory closed, and his employees relocated to Calcutta, settling in the current Tiretta Bazaar district in the city's central area. Atchew may have failed in his attempt, but his expedition inspired others from Canton (Guangdong province) to migrate to Calcutta, an emerging metropolis in the East, by the early nineteenth century.

New Chinese immigrants found employment in the leather industry, as well as in sugar mills. Leather items were in high demand among Europeans in India and the growing Bengali middle class. Bengalis and Europeans hesitated to work with animal hides, which the Chinese migrants didn’t. The tanneries were an eyesore for the city’s ruling British elite, so they were relocated to the eastern marshes in Tangra, which later became known as “Chinatown.”

In addition to sugar mills and tanneries, Chinese immigrants established shoe stores, laundry services, and dental clinics in Calcutta. Tiretta Bazaar and Tangra became Calcutta’s hub for Chinese immigrants and the birthplace of a new cuisine: Indo-Chinese.

However, not everyone is convinced that the fusion between Indian and Chinese food occurred in the 18th century. Many argue that the Silk Road trade and the exchanges along the Indo-Chinese border, including Myanmar, Tibet, Bhutan, and Nepal, played a significant role in the development of Indo-Chinese cuisine.

Food Trails on the Silk Road

Although much of what we call Indo-Chinese cuisine traces its origins to Chinese immigrants in colonial India, cultural exchanges along the Silk Road and the Tea Horse Road played a crucial role in shaping the cuisine.

Food historian Puspesh Pant says Indo-Chinese cuisine is "the result of several isolated encounters,” and these contacts weren’t restricted to migrations to Calcutta.

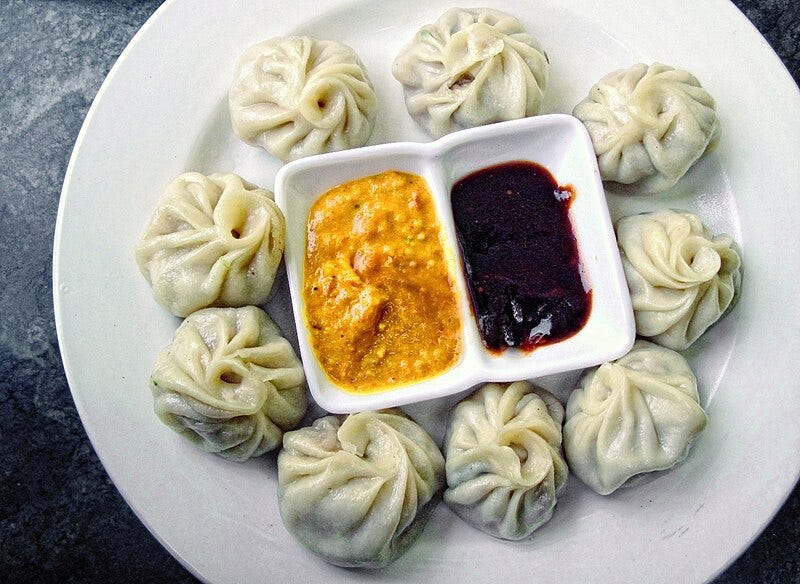

Consider the evolution of the momo, a type of steamed dumpling that originated in Tibet and Nepal. The two nations were influenced by trade with China and India, incorporating elements of both cuisines into their local fare.

Buddhism from India had a profound influence on Tibetan religion and culture, while noodles, tea, and dumplings from China became staples of Tibetan cuisine. The momo likely originated in Tibet before spreading to the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal, and across the Indo-Gangetic plains in North and East India.

The Silk Road trade facilitated the spread of Buddhism from India to China, as well as the introduction of Indian spices, including black pepper, cinnamon, and ginger. Chinese-style woks were introduced in the Indian subcontinent, where they influenced the design of the popular cooking vessel known as the karahi.

A karahi is a thick, circular cooking pot, similar to a wok. Although it existed in India since the Vedic times (1500-600 BC), its larger versions bear resemblance to woks, suggesting a cultural diffusion along the Silk Road.

The Silk Road and Tea Horse Road trades resulted in the exchange of various ingredients and the flow of dishes and cooking utensils between India and China. However, most popular Indo-Chinese foods can be traced to the culinary fusion that originated on the banks of the Hooghly River.

Blending Chinese Cooking Styles with Indian Ingredients

The first Chinese immigrants to India hailed from Canton, but later people arrived from other provinces of China. Interestingly, the occupations they pursued in Calcutta were closely tied to their origins in China.

Sugar mill workers were mainly Cantonese. Most of the tannery workers and residents of Tangra were Hakka, a people group distributed throughout several southern Chinese provinces. The Hakka people are famous for introducing the most popular style of Indo-Chinese noodles, known as Hakka noodles. A typical Hakka noodle dish is made by stir-frying sliced veggies in a wok with thin noodles and a dash of soy sauce. Toppings, such as chicken, shrimp, eggs, or a combination of these, are added and typically served with chili sauce.

The dentists primarily came from Hubei province. Shanghai migrants ran dry cleaning services. You’ll still come across many laundromats run by their descendants, named “Shanghai Dry Cleaners.”

Each immigrant community established Huiguans, social clubs that served as networking centers for newcomers. They coordinated education, housing, and employment for people from similar backgrounds. Someone from Canton was likely to seek a Huiguan composed of other Cantonese who had moved before them.

Most of the early immigrants were men who arrived without their families. An essential role of the Huiguans was also to make funeral arrangements for those who passed away, as sending the body back home was an expensive affair.

There was a fair balance of immigrants from different parts of China, and they brought a diverse array of foods. Though men dominated many professions in Chinese society, the restaurant industry had a healthy male-female ratio. The kitchens were family-run, and even today, if you visit Tiretta Bazaar before 8 a.m., you’ll see Chinese families serving traditional foods whose recipes are well-kept secrets.

Chinese ingredients weren’t always readily available in India, especially in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Today, you can get a bottle of Shaoxing Wine or fermented black bean paste in major Indian cities; the early Chinese immigrants had to adapt to local ingredients.

To appeal to Indian customers, the sauces were thicker and spicier than in traditional Chinese cooking. Cumin, coriander seeds, and black pepper became popular ingredients. The food combined the best of both worlds. Although it deviated from traditional Chinese cuisine, a new culinary genre, Indo-Chinese, emerged.

Influencing food habits across social classes

Unlike European food, which was limited to Calcutta’s aristocracy, Chinese food began on the streets and in small eateries. Only a few European foods are popular in Bengal, including fish fry (a breaded deep-fried fish derived from schnitzel), chicken stew, cakes, and pastries.

In contrast, Chinese cuisine was widely accepted. Chinese cooks and food vendors were astute observers who knew how to read the crowd. By adjusting the levels of oil and spices, cooks created several variations of the same dish.

The streets of Chowringhee (Calcutta’s office sector) offer a different take on chicken chowmein than Eau Chew, the city’s longest-surviving Chinese restaurant. However, the fundamentals of sweet, sour, and spicy components of Chinese cuisine remained consistent. Because of this, most Bengalis felt more at home with Indo-Chinese food when trying new dishes.

Eau Chew is an outstanding example of a restaurant that brings together the city’s diverse population, regardless of socioeconomic status. Achumpa Huang founded the restaurant in 1927, using utensils from his hometown in Southern China. Initially, the eatery fed hungry laborers. However, the Huangs hoped to attract an upscale clientele.

The name “Eau Chew” translates to “Europe” in Mandarin, emphasizing the Huang family’s ambition to offer Chinese cuisine that is elegant and suitable for the refined palate. The restaurant served pork chops to European customers and had a broad menu. They blended European-inspired dishes with Indo-Chinese and traditional Chinese fare.

Eau Chew continues to offer a variety of unique items that you won’t find in other Chinese restaurants, such as Josephine Noodles, named after Josephine Huang, a third-generation restaurateur who invented a new form of pan-fried noodles with a plethora of toppings, including vegetables, meat, fish, shrimp, and more. Another highlight of theirs is the chicken in wine sauce, which may have been inspired by coq au vin but has distinct Chinese characteristics.

Eau Chew altered the perception of Chinese food. People saw Chinese as an acceptable fine dining option. While the restaurant may lack the glitz and ambiance of newer establishments, it compensates with exceptional meals prepared by the Huang family.

Indo-Chinese innovation persisted long after India’s independence. In 1975, Nelson Wang, a Chinese-Indian chef, invented the famous “Manchurian” category of Indo-Chinese. Manchurian is a sweet and salty dish with a dark hue, served with chicken or vegetables. Despite its name, it bears no resemblance to traditional Manchu cuisine; instead, it integrates Indian components, beginning with chili, garlic, and ginger, and concludes with soy sauce rather than spices. Deep-fried chicken, mushrooms, or cauliflower is stirred into the sauce and served.

Wang introduced chicken Manchurian at China Garden, Mumbai’s oldest Chinese restaurant. It quickly became a hit, and even Indian restaurants started serving it, with their own interpretation. You’ll come across Manchurian dishes on the menus of street food vendors and five-star establishments.

Indo-Chinese had cut across social barriers.

From its humble origins in the streets of Calcutta, the cuisine gained popularity worldwide, with restaurants in the UK, the US, and Canada. In 2010, I was pleasantly surprised to see an upscale Indo-Chinese restaurant in Arlington, Virginia, at full capacity on a weekday.

The number of Chinese-Indians declined over the years, especially after the Sino-Indian War of 1962. Many Chinese Indians were falsely accused of having ties to China and aiding the Chinese Communist Party. Facing persecution and stigma, most of them left the country.

There were only 2,000 multi-generational Chinese in Calcutta in 2013. More Chinese ex-pats work in India than Chinese Indians. Despite their departure from India, their influence on Bengali food endured.

If you visit Philadelphia’s Chinatown, you’ll notice that Chinese Americans manage most businesses and restaurants. However, don’t be surprised if you go into a Chinese restaurant in Calcutta’s Chinatown and discover Bengali cooks and front-of-house staff working hard under the supervision of a Chinese family to preserve years of traditions.

Thanks to e-commerce and an increase in imports, Chinese ingredients are now easily accessible, making it easier than ever to prepare an Indo-Chinese meal. This adds to the increased popularity of Chinese cuisine among home cooks.

To wrap up our scrumptious discussion, I’ll leave you with an image of a ginger fish dish I made. Although there are various variations of this dish, the recipe I prefer involves heating oil in a wok and adding julienned ginger, scallions, and a small amount of garlic. As the oil becomes fragrant, add a cube of onions and strips of flat white fish, followed by soy sauce, sugar, and a pinch of black pepper.

Cook until the fish is done. This pairs well with the Cantonese-style pan-fried noodles pictured at the beginning of the story. Be sure to wash it down with jasmine tea in the end.

History influences our food. If you enjoyed how migrations and trade resulted in the genesis of Indo-Chinese cuisine, check out other stories from humanity’s culinary past here.

Do you love exploring the mysteries of lost civilizations and the rich cultures of the ancient world?

Share this story with friends and family, and don’t forget to subscribe to this newsletter for more fascinating insights!

If you enjoyed this story and would love to read more such write-ups, please upgrade to a paid membership.

References

Sankar, Amal (2017). “Creation of Indian–Chinese cuisine: Chinese food in an Indian city”. Journal of Ethnic Foods.

Lahiri, Indrajit (2021). Food Kahini (translated from Bengali).

Toronto Life (2017) “Lunch Lesson: Getting schooled on Hakka Indian cuisine at Yueh Tung.”

Fascinating article, I must make another trip to Calcutta

This was a great read, and personally I almost feel a sense of relief when Indo-Chinese history is explored. And through food — even better!