Welcome to a special edition of Forgotten Footprints. Today's story will be presented by

of Chai Biscuit Tales, a newsletter that focuses on the history and culture of 19th-century India, with particular attention to North East India. Most of you have heard about the Silk Road trading network connecting China to Europe. However, another trading network played a significant role in the exchange of goods in Asia and affected regional geopolitics: the Tea Horse Road.Let’s learn about it.

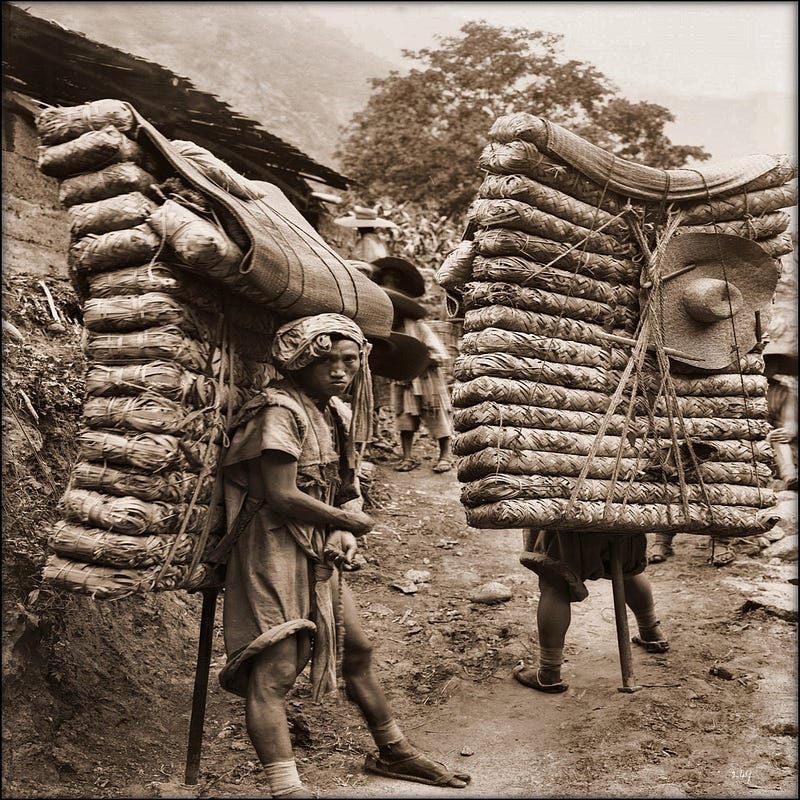

Ancient roads once wove together distant lands, traversed by mules and caravans long before modern transport. Though many of these trails have faded from the landscape, they remain alive in the memories and oral traditions of the communities whose ancestors once journeyed along them.

The Tea-Horse Road was one such thriving network of caravans, mules, and traders from different communities, linking the hinterlands of China to Tibet, South and Southeast Asia. As the name suggests, this trade primarily revolved around horses and tea. Horses from Lhasa were exchanged for Chinese tea, specifically Pu’er tea from Yunnan. The horses of Tibet were actively sought after by China and Southeast and South Asian states to strengthen their military.

With the introduction of Chinese tea to Tibet in the 7th century CE, the Tea-Horse Road became a bustling trail that would continue for centuries. We’ll learn how this lesser-known trade network transformed the region’s economy, whose effects are still felt today. But before discussing the origins of the Tea-Horse Road, we first need to understand the historical significance of Pu’er tea.

The Six Great Mountains and the Origins of Pu’er Tea

The Chinese were the first to domesticate the camellia sinensis plants and initiate the culture of tea drinking. According to Chinese folklore, Shen Nong, an ancient tribal leader, discovered tea when he was saved from poison by drinking wild tea leaves brewed in water. Tea became widely consumed in southern China between the 6th century BCE and the 3rd century CE. Tea drinking became popular nationwide during the Tang dynasty (618–907).

Tea production in China has historically been centered around the famous “Six Great Tea Mountains” in Xishuangbanna (Sipsongpanna), in Yunnan's eastern Mekong River region. These mountains—Yiwu, Yibang, Gedeng, Manzhuan, Youle, and Mansa—were renowned for producing high-quality tea. They were located geographically, with one summit after another at an elevation of 1200–1800 meters. Their favorable climate and fertile soil made them ideal for cultivating tea plants.

Among them, Yiwu became synonymous with the birthplace of Pu’er. It might be because, among the other regions, Yiwu was the only center retaining Pu’er production’s authenticity and craft.

Chinese historians like Jinghong Zhang have argued that Yiwu became a renowned center of Pu’er tea production and distribution during the Qing period (1644–1911). The Qing government paid particular attention to the ethnic communities living in the border areas of Yunnan. The rulers initiated a system of indirect governance in these areas, appointing local officials and allowing them autonomy in exchange for taxes and tribute (primarily as Pu’er tea).

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Pu’er from Yiwu was sent as tribute to the Qing emperor, symbolizing the loyalty of local communities. Yiwu also emerged as a significant tea trading center under Qing rule, attracting Han Chinese and Hui Muslim merchants to take advantage of new opportunities.

These historical factors increased Yiwu's value in modern times. The importance assigned to Yiwu is such that many Pu’er connoisseurs undertake a pilgrimage to the site to honor the birthplace of the “sacred dark tea.”

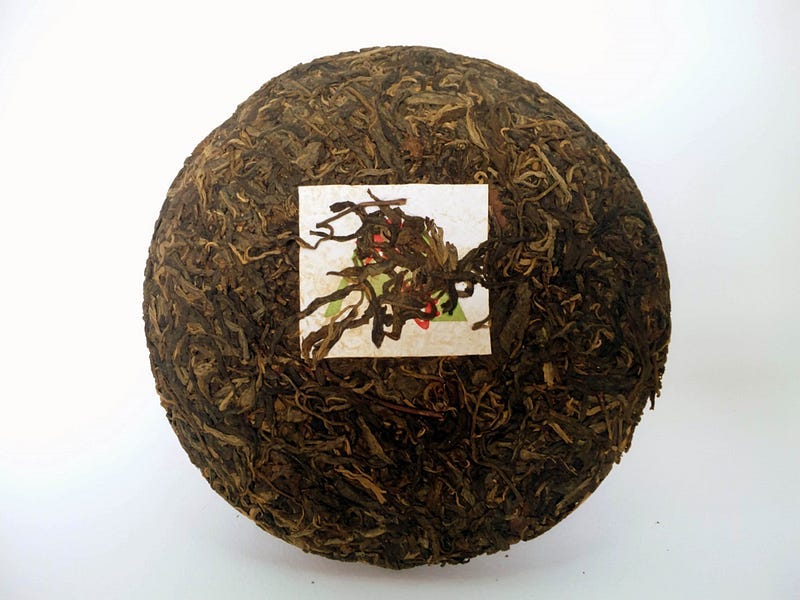

Pu’er tea is named after the prefecture of Pu’er in Yunnan and is commonly known as dark tea (hei cha). Unlike the regular short-leaf variety of black tea, which is made from camellia sinensis sinensis, Pu’er tea was processed from camellia sinensis assamica, a long-leaf variety. The value attached to Pu’er was because of its aging process. Like wine, Pu’er tea gets better with time. Further, unlike loose tea, this variant is molded into cakes or bricks and wrapped carefully in bamboo leaves. This made Pu’er tea convenient for long-distance trade.

Pu’er tea, in its initial form, is called maocha. The maocha undergoes several processing stages, resulting in three distinct varieties: green, fermented, and post-fermented. This post-fermented version was widely sold in compressed forms to Tibet and beyond through the Tea-Horse Road.

It isn't easy to determine how Pu’er tea became a culture among the Chinese. Some argue that its benefits were accidentally realized due to caravan transport. Others claim that Cantonese discovered and improved the flavor over the years through tasting activities and interactions with tea producers and consumers.

Interestingly, however, the tea was not produced in Pu’er and was known and traded long before the Pu’er Prefecture was established. Scholars have argued that Pu’er might be a pronunciation variation of words bu’ri and bu’er, likely derived from the names of ancient ethnic groups such as bu and pu.

Earlier, the production and trade of this tea were controlled by several non-Han ethnic minority communities like Bulang, Deang, Wa, Hani, and Jinuo, who lived in Yunnan’s border areas. During the Qing dynasty, when the population increased significantly in China’s heartland, many displaced people, including Han Chinese and Hui Muslims, migrated to these less populated border areas.

The involvement of the Han Chinese and Hui Muslims in production and distribution further contributed to the spread of the Pu’er tea trade from the western frontiers of China to other regions. Although the Tea Horse Road had existed since the Tang dynasty, it witnessed unprecedented traffic during the Qing dynasty. New areas such as Burma and India were connected by road during the Qing era. However, this resulted in the declining importance of China’s trade relationship with Tibet.

Let’s see how Tibetans developed a love for Chinese tea and what they had to offer in exchange.

When did Chinese tea reach Tibet?

The arrival of tea in Tibet is associated with a significant diplomatic and cultural exchange with China during the Tang Dynasty. The foundation of the Tibetan empire (618 and 877 CE) under Songtsen Gampo coincided with the rise of the Tang dynasty in the 7th century. In Tibetan history, Gampo is known as the first of the three Dharma (religious) kings of Tibet and is associated with the introduction of Buddhism in Tibet.

After unifying various territories under a single empire, Gampo sought a marriage alliance with the Chinese to secure political peace on the borders. The Chinese emperor Taizong married his niece, Princess Wencheng, to Gampo. Since gifts were an essential part of Asian politics to secure favor, the two dynasties engaged in many cultural exchanges. The Chinese received horses, borax, yak tail, and wool. For Tibet, Pu'er tea was the most vital item that flowed into its borders.

The diplomatic relations between the Tang dynasty and the Tibetan empire marked the latter’s dependency on this beverage, increasing Chinese influence in Tibetan territories.

After its introduction, tea expanded into Tibet’s daily and spiritual practices, with rulers and lay people sipping several cups of Pu’er daily. Pu’er also fueled Buddhist monks to focus on their meditation and daily rituals.

Some Tibetan nomads might have even consumed up to 40 cups a day!

The Pu’er tea also has many health benefits, from lowering cholesterol levels to blood pressure, which balances the Tibetans’ rich diet of yak meat and cheese. They eventually started mixing fermented tea leaves with yak butter and salt to create a unique brew, which soon became a favorite. This high-calorie butter tea provided a nutrition boost to Tibetans during winter.

Tea could not be grown at the high altitude of the Tibetan plateau. Hence, the Tibetans relied on the horse and mule caravan trade to get their beloved tea. But they weren’t going to let the Chinese merchants return empty-handed. China depended on the Silk Road trade for its supply of horses, but now it had an alternative closer home.

The establishment of the Silk Road was greatly influenced by the Han Empire’s quest for political alliance with the Yuezhi tribe in the 2nd century BC. During a mission, a Han ambassador, Zhang Qian, discovered the ‘blood-sweating’ horses in the Ferghana Valley of present-day Uzbekistan. Modern historians have long since argued that blood-sucking parasites on the horses’ mane caused the illusion of them sweating blood. However, the Han rulers regarded these horses as heavenly signs that would help them defeat their arch nemesis- the nomadic Xiongnu, who were famed for their horse archers.

The acquisition of the horses of Ferghana and the idea of a profitable silk trade with Central Asia marked the beginning of the Silk Road trade. However, China was opened to new possibilities with the beginning of Sino-Tibetan trade through the Tea Horse Road. The Tibetan horses reduced China’s dependency on the “heavenly horses” of Ferghana.

The Ancient Tea Horse Road

The Cha Ma Gu Dao ( ancient Tea Horse road) received a massive boost from the newly established Sino-Tibetan trade in the 7th century CE. This route is sometimes compared to the Southern Silk Road, although silk was not the primary commodity exchanged through it. Unlike the well-defined Silk Road, the Cha Ma Gu Dao was a network of rugged tracks through the high mountain ranges traversed by humans alone on their feet and horses.

Apart from horses and tea, the road was also utilized for other exchanges, ranging from commercial to spiritual. With different stopping points, the caravans would take months to reach their destinations. The caravans halted at monasteries, combining pilgrimage and trade, and at marketplaces where they could sell other goods, including salt, silks, etc.

Tea was then sent by caravans from several commercial centers in the provinces of Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guizhou to Lhasa, where merchants from other parts of Tibet assembled. The trade did not end at Lhasa but extended beyond into Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam and Laos and South Asian regions like Kalimpong, West Bengal and Gangtok, Sikkim in India.

Despite the risks and difficulty of the trade, the Tea Horse Road remained active from the 7th century until the mid-20th century. The advent of motor vehicles, well-developed networks, and political developments in China and Tibet gradually pushed the historic adventures along the Cha Ma Gu Dao into popular memory. Many original trails have vanished, but some spots attract trekking tourists seeking an authentic glimpse into the past.

However, Pu’er tea remains central to the new trade networks. If anything, its value has only increased over the years. Through his ethnographic study, Jinghong Zhang revealed how the cost of Pu’er tea had increased from ¥10,000 in the 1990s to ¥1 million in the early 2000s.

He says such increasing costs are influenced by ‘connoisseurship’ around the Pu’er tea tradition. Visits to Yiwu, the “sacred” site for Pu’er tea lovers, have contributed to the growing commercialization of this tea variety. In Yiwu, the tea makers shape the Pu’er tea into cakes or bricks using their hands. This handcrafted, authentic experience further increases the brand value of the Pu’er, as seen from its high selling costs.

It is safe to say that although the ancient pathways may have been replaced with newer ones, Pu’er tea’s value and consumption remain popular, and we can credit it to the Tea-Horse Road.

Do you enjoy tales from lost civilizations and cultures from the ancient world and the Middle Ages?

Share this story with your friends and family and subscribe to this newsletter.

References

Freeman, M., & Ahmed, S. (2011). Tea Horse Road: China’s ancient trade road to Tibet. River Books.

Fuchs, J. (2008). The Tea Horse Road. The Silk Road, 6(1), 7–15

Xiao, K. (2023). From highlands to lowlands: The Pu’er tea trading network and ethnic-group interactions in the frontier of Yunnan, 1662–1796. In L. Dzuvichü & M. Baruah (Eds.), Objects and frontiers in modern Asia: Between the Mekong and the Indus (pp. 93–112). Routledge.

Zhang, J. (2014). Pu’er tea: ancient caravans and urban chic. University of Washington Press.

Thanks for this! The tea horse road has interested me since I first learned about it while doing some research for a novel a few years back. Always happy to gain more context for it.

Just fascinating, thank you‼️