Did the Mongol Invasions End the Islamic Golden Age?

Settling the debate on the impact of the Sack of Baghdad

In a recent conversation with

of , we discussed the impact of Mongol invasions on the loss of knowledge in the medieval world.I recommend you check out his post “Unless You are the Mongols,” and the rest of his publication for cool stuff from history and archaeology. Popular discourse suggests that Hulagu Khan’s devastating raid on the Abbasid Caliphate and destruction of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad had a catastrophic effect on world history.

Knowledge transmission took a backseat. Humanity’s progress came to a standstill.

But is this true?

To find out, let’s turn back the clock.

On January 29, 1258, Al-Musta’sim, the last Abbasid Caliph, had his worst nightmare come true. After cheering for the destruction of Alamut (the Nizari Islamili capital), the caliph found the Mongol war machine, led by Hulagu Khan, at his doorstep. The caliph underestimated how little support he had in the Islamic world. He regretted not paying tribute to the Mongols, but it was too late.

Baghdad suffered terrible devastation. Among the casualties was the House of Wisdom, one of the most expansive libraries in human history. The river Tigris became black with the ink of books thrown.

Is this popular narrative of Mongols ending the Islamic Golden Age accurate? Or was creativity in the arts and sciences in the Islamic world on the decline long before Hulagu’s attack? Why didn’t later Islamic empires like the Mughals, Safavids, and Ottomans reach the same level of technological growth as the Abbasid Caliphate?

Let’s find out the answers.

Scientific Progress Under the Mongol Rule

The Islamic Golden Age was a time of cultural, economic, and scientific growth in the Islamic world that lasted roughly from the eighth through the thirteenth centuries.

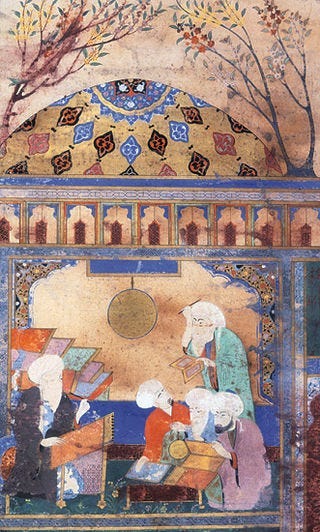

Several Islamic intellectuals, such as Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Al-Biruni, Al-Khwarizmi, Omar Khayyam, and Ibn Rushd (Averroes), made substantial contributions to a variety of sciences during this period, including mathematics, astronomy, medicine, chemistry, and philosophy.

Human advancement during the Islamic Golden Age had far-reaching consequences, as European scholars translated numerous Islamic texts. These translations played an essential role in the Italian Renaissance.

Baghdad, the Abbasid Caliphate's capital, was the Enlightenment epicenter. Hence, many historians see Hulagu’s destruction of Bagdad in 1258 as the end of the Islamic Golden Age.

Hulagu’s raid concluded the Mongol onslaught against Islamic civilizations. The story began with the annihilation of the Khwarezmian Empire by the great conqueror Chinggis Khan (Genghis Khan).

Chinggis sent a trade envoy with a diplomatic proposal. But they were killed by Inalchuk, the governor of Ortar and Muhammad’s uncle, accusing them of spying. The Shah refused to hand over Inalchuk to the Mongols for a trial. The murder of the diplomats led to the Great Khan attacking the Khwarazmian empire.

Chinggis and his men depopulated the region and ruined irrigation systems to make an example of Muhammad II.

A few decades after Chinggis’ death, his grandson Mongke, the great Khan of Mongols, ordered an expedition to conquer the Middle East. The man in charge was Hulagu.

The Mongols are widely seen as civilization destroyers. But a closer look reveals they were patrons of the arts and sciences. Since the time of Chinggis, Mongol rulers spared scientists, artists, religious leaders, philosophers, and skilled workers. This ensured that the development of new knowledge and artistic expression continued unabated during Mongol rule.

The famous astronomer Nasir-al-din Tusi impressed Hulagu. A believer in astrology and astronomy, the Mongol general ordered an observatory built at Maragheh, now in Azerbaijan.

Tusi took 400,000 books from the House of Wisdom to his observatory before the library’s destruction. His planetary movement recordings, published in the Zij-i-Ilkhani, were the most advanced during the Middle Ages. The treatise later aided Copernicus in developing a heliocentric understanding of our universe.

Kublai Khan, Chinggis’ grandson, asked Hulagu to send Islamic scholars to China. These scholars introduced new scientific ideas, such as the astrolabe, the concept of unequal hours, and spherical globes that showed oceans, rivers, and distances along the roads.

The east-west connection boosted technological interaction across Eurasia. Knowledge of Islamic sciences spread, and Muslim academics rose to positions of power in Mongol courts.

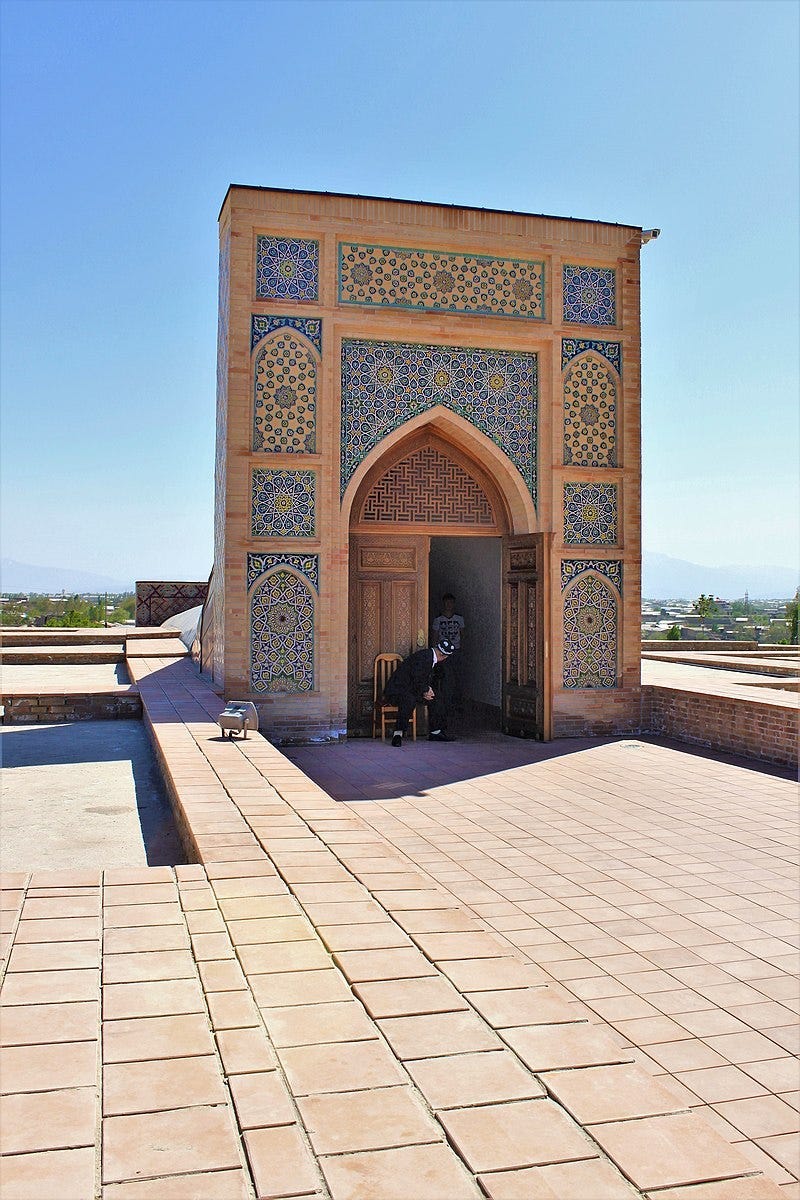

In the early 15th century, Turco-Mongols like Ulugh Beg, grandson of the last great Steppe conqueror Timur, continued to fund scholarship and constructed the world’s largest observatory in Samarkand, attracting scientists worldwide.

The assumption that Mongol invasions ended the Islamic Golden Era is incorrect and must be refuted.

After the destruction of Baghdad, the Islamic world had great empires with the latest military technologies, such as the Safavids, Ottomans, and Mughals. So why didn’t the legacy of scientists and philosophers like al-Bruni, Avicenna, Omar Khayyam, and al-Tusi continue?

No Country for Scientists

It is quite impossible, that a new science or that any kind of research should arise in our days. What better we have of sciences is nothing but the scanty remains of bygone better times- Al-Biruni

The quote by al-Biruni, almost two centuries before Chinggis Khan’s forces set foot on Khwarazm, reveals a story of the decline of scientific research in the Islamic world.

During the Ancient and Middle Ages, science depended on patronage. Rulers and influential families play an important role in promoting sciences and arts.

What would the Italian Renaissance be without the Medicis?

The Barmakids, an aristocratic family from Balkh, played a crucial role in financing the translation of Hindu mathematics and scientific literature into Arabic in the Islamic world. They also funded Baghdad’s first paper mill.

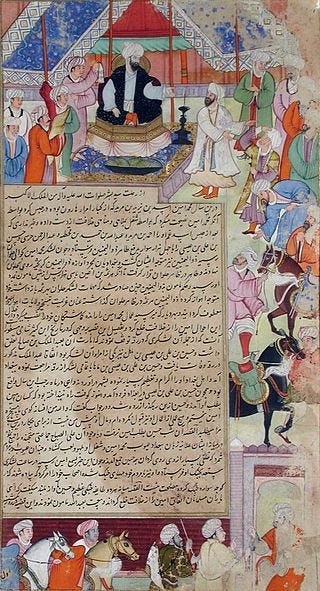

Prominent families persuade those in power to invest in human growth, which increases citizens’ prosperity. Later Islamic dynasties, such as the Mughals, Safavids, and Ottomans, spent lavishly on arts and architecture, erecting magnificent monuments, but were not interested in scientific study. During the 16th and 18th centuries, most writings in science and philosophy were commentaries on older works. There was little originality.

Though historians no longer subscribe to the theory of Ottomans banning printing, there is sound evidence to suggest they discouraged Muslims from printing works in Arabic and Turkish. The Ottoman Sultan authorized printing books in Turkish and Arabic only in 1729. Calligraphy was the preferred method for creating beautiful handwritten books. Such books had artistic value, but they restricted the spread of knowledge.

Printing was likewise limited in Mughal-ruled India until the Portuguese arrived.

This short-sighted vision has roots from the tenth century onwards, as we can see from the writings of Al-Biruni. There were scientists and philosophers, but the rulers viewed human development as secondary to building spectacular monuments. The Khwarazmian empire, for example, had tremendous wealth because of the Silk Road trade, but they did not invest in education.

Lack of support for scientific study and adoption of new technologies in the Islamic world resulted in them lagging behind their European rivals by the end of the 17th century.

What about the Islamic world’s scientific temperament? Did subsequent dynasties foster a culture of curiosity and open-minded discussions, as the Abbasids did?

Internal Schism: Rationality vs Tradition

The end of any golden age in human history does not occur in a vacuum. We are social animals, and the type of society we live in significantly impacts how we form ideas.

During the reign of Caliph al-Mamun, the theologian Ibn Hanbal said every Muslim must strictly adhere to the Quran and Hadiths and reject any external influences. Mutazilite philosophy, which was based on rationality, was an opposing school of thought to Hanbal’s traditionalist approach. Aristotelean thinking inspired Mutazilites, whose prime focus was freedom of thought and expression.

The caliph imprisoned Hanbal and supported the Mutazilite idea of free will, ushering in progress. But later, rationalists were not so lucky.

11th-century traditionalist philosopher Al-Ghazali criticized Avicenna’s rationalist approach to Islamic theology. Ghazali exerted tremendous power in the Islamic world. He persuaded the rulers that the Aristotelean sciences had to conform to the religious perspective of science. Ghazali’s critique, the Incoherence of Philosophers, launched a scathing attack on rational thought.

When you confine sciences to the framework of religious ideology, there is always a problem. If an invention contradicts religious belief, it is rejected. Ghazali successfully sidelined several mathematicians, theoretical scientists, philosophers, and astronomers. Nobody dared to challenge Ghazali for a generation.

But the world does not wait. For every civilization that rejects a groundbreaking idea, others are willing to capitalize on it.

Averroes was the first to question Ghazali’s ideas in his rather cheekily titled work The Incoherence of Incoherences. He defended rational Islamic sciences from Ghazali’s criticism, but ultimately, few takers in the Islamic world supported Averroes’ ideas. Instead, the Latin and Hebrew translations of his work found an audience.

According to historian Frederick Starr, Ghazali’s beliefs established the groundwork for an extremely restricted Islamic law with a mechanism to stifle free thought. As a result, a religious establishment acting independently of the state influenced scientific growth.

Rational thinking had taken a back seat in the Islamic world long before the Mongol invasions.

The Mughals, Safavids, and Ottomans dominated the Silk Road trade, which made them wealthy. But as we discussed, prosperity was not accompanied by advancement in sciences.

Rather than blaming Mongols for ending the Islamic golden age, we can credit them for ending the restrictive institutions that stifled sciences. During Mongol rule, there was a revival in the Islamic world, as the religious scholars lost their influence for at least a century.

Ulugh Beg calculated the solar year's length more accurately than Copernicus decades before him. His assassination and the destruction of his observatory by his son, supported by religious fanatics, marked the end of any hopes of a great Renaissance in the Islamic world.

After reading this story, I’d like to know your opinion about the impact of the Mongol invasions on knowledge.

Please vote.

Do you enjoy tales from lost civilizations and cultures from the ancient world and the Middle Ages? Share this story with your friends and family and subscribe to this newsletter.

To support the newsletter, consider a paid membership or a donation here.

References

F.Jamil Ragep. Freeing Astronomy from Philosophy: An Aspect of Islamic Influence on Science, Osiris, 2001.

Jack Weatherford. Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World New York, Crown Publishers, 2004

Meri, Josef W. Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge, 2005.

Michael Prawdin. The Mongol Empire: its rise and legacy. New Brunswick: Transaction, 2006.

S. Frederick Starr. Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane. Princeton University Press, 2013.

I like history, but I'm not familiar with Islamic History. As such, when I read it, I always find that a name or two that I recognize will jump out and then I'll be lost again. There's just so much context that I'm missing that it feels almost like jumping into a fantasy novel.

But even with history that I am familiar with, I'll find that it only extends back so far, say to the French Revolution and then I'm once again needing to learn new names and ideas and lore. And when I'll read or listen to things about it there will be some MAJOR event that I'm learning about for the first time.

As for science I think the biggest impediment has been the idea that there is some secret or forbidden knowledge. I think for instance of Forceps. How many more people could have been saved if that had been more common? Or all the closely guarded maps of the "Age of Exploration". Not that I have a solution but even now I think the idea of a tech advantage or limited use knowledge is likely holding people back.

I don't know enough to say but there are a lot of clever people all over the world coming up with solutions to problems that I'll never face. Even in an era of relatively little progress, someone's coming up with a new way to do something. And it takes time with some tech for there to be enough familiarity that a person can improve on it. So I imagine that the Mongols being so widespread might have enabled many ideas to spread and become a springboard for later ideas even if it wasn't an immediate burst of innovation.

Nicely done, Prateek! I'm gonna share this piece via Notes so folks can see that we once again passed a mental torch in this footrace of understanding.