Did Hunter-Gatherers Build Göbekli Tepe?

New insights into the architects of the iconic megaliths

Göbekli Tepe is one of the most talked-about archaeological discoveries in the last decade. The site in Turkey’s Şanliurfa Province has become the subject of a heated discussion regarding the origins of organized religion and farming.

The megaliths at Göbekli Tepe, erected between 9600 and 8700 BC, have also piqued the interest of alternative historians who postulate that survivors of a lost Ice Age civilization built the monument. Others have proposed that Göbekli Tepe was the Garden of Eden, while some believe that Sumerian mythical beings, the Anunnaki, built it.

However, such theories are not supported by evidence.

Göbekli Tepe was discovered during an archaeological survey by the University of Chicago in 1963. Unfortunately, it was ignored, and it wasn’t until 1995 that archaeologist Klaus Schmidt “re-discovered” the site and began excavation. Schmidt’s initial assumption was that hunter-gatherers built the remarkable megaliths. He passed away in 2014, and since then, significant developments have taken place, challenging our initial understanding of the site.

In this special edition of Forgotten Footprints, I’m joined by

Khare, who runs the Geosophy newsletter, to explore whether Schmidt’s assumption that hunter-gatherers built Göbekli Tepe still holds. Devayani has a deep interest in Earth Sciences and will provide a geographical perspective on whether the site could’ve supported human habitation. I recommend you check out her page, which covers the intricate connections between the physical environment, biodiversity, and human history.Overview of Göbekli Tepe

Göbekli Tepe, meaning “pot-bellied hill,” is in Taş Tepeler (Stone Hills), at the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, overlooking the Harran Plain. Taş Tepeler has several archaeological sites, including Göbekli Tepe, Nevalı Çori, Karahan Tepe, Hamzan Tepe, Sefer Tepe, Kurt Tepe, Harbetsuvan Tepe, Sayburç, and Ayanlar Höyük, all from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) period.

As the name implies, PPN refers to a period in the Neolithic (New Stone Age) before the discovery of pottery. Crop and animal domestication were in their early stages.

PPN is split into two periods: PPNA and PPNB.

PPNA corresponds to the early part of the era, roughly 10,000 BC to 8700 BC, whereas PPNB lasted between 8800 BC to 6500 BC. Göbekli Tepe dates back to the PPNA era when we saw a hybrid lifestyle with elements of sedentism and hunting-gathering. As PPNA was an era in transition, there can be confusion in identifying whether the people who built Göbekli Tepe were hunter-gatherers or farmers.

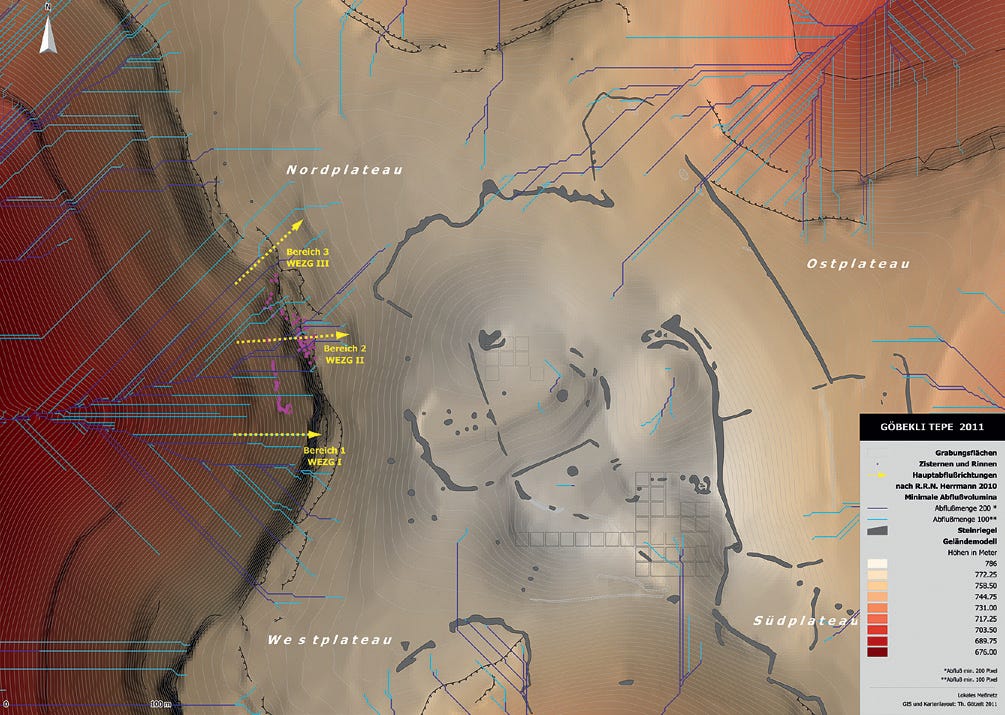

The aerial view of Göbekli Tepe shows four circular complexes, Enclosures A, B, C, and D, with diameters varying from 10 to 30 meters. Geophysical surveys found 16 more similar enclosures. You’ll also notice some smaller rectangular compounds.

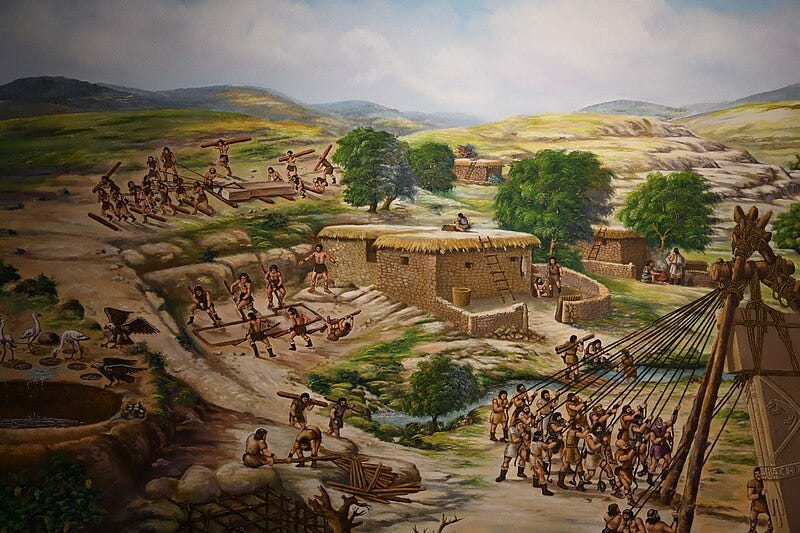

Each circular enclosure has two giant T-shaped pillars (5.5 m tall) in the center, flanked by multiple smaller T-pillars. Surveys show that there may be around 200 similar pillars at the site. The T-pillars portray humans and animals, primarily males. You’ll come across foxes, boars, cranes, snakes, leopards, and vultures shown on the structures.

Schmidt first thought Göbekli Tepe was a temple where hunter-gatherers gathered for rituals. He concluded that the architects of Gobekli Tepe could not have lived sedentary lives because of the lack of water sources and minimal evidence of homes. Instead, they gathered at the site for religious activities and feasting.

Did people live at Gobekli Tepe?

According to popular belief, people first lived in nomadic hunter-gatherer societies before settling down and cultivating land some 11,000 years ago, when global temperatures rose, and the climate was ideal for farming. But this narrative isn’t backed by archaeological evidence.

Before farming began, humans cultivated and processed wild grains for thousands of years. Cereal processing in the Near East dates back to 23,000 BP and was first discovered at the Paleolithic Ohalo II archaeological site in northern Israel.

A few millennia before the PPNA period, the Natufian culture (15,000 to 11,500 BP) in modern-day Israel was semi-sedentary. Its inhabitants lived in settled communities, processed wild grain, hunted animals, and brewed beer.

Towards the end of the Natufian culture, the earth experienced the Younger Dryas, a geological period of abrupt cooling roughly 12,900 to 11,700 years ago. It marked a significant climatic transition at the end of the last Ice Age. Some researchers have suggested that the Younger Dryas’ near-glacial conditions profoundly affected megafauna - referred to as the late Pleistocene extinction. Others believe that megafauna extinctions began way before this period. While the exact cause of the Younger Dryas is hotly debated, the period saw a reduction in megafauna, such as giant beavers, mammoths, mastodons, elk, most species of odd-toed and even-toed ungulates, and ground sloths.

As the Younger Dryas spell ended and the climatic conditions stabilized, human populations faced challenges in game hunting as animal populations dwindled. These difficulties may have caused humans to take up the back-breaking labor of farming and processing wild grains and slowly embrace sedentism. The subsistence patterns of early semi-sedentary communities, such as the Natufians, also hint at the same transition.

When Göbekli Tepe was discovered and dated to the 10th and 9th millennium BCE, why did researchers surmise that the site was for religious gatherings only and not a settlement? And what did it take to turn this interpretation on its head?

Cisterns & Civilizations

Early interpretations of Göbekli Tepe as primarily a religious site were based on the lack of a readily available drinking water source, which raised questions about the site's ability to support a permanent settlement.

No natural springs were found at the site at the time of the study, and the geology made it unlikely that springs existed in the past. The nearest water source, at the village of Edene Köyü, is located approximately 5 km northeast of Sanliurfa. It would have been difficult to obtain a regular water supply across this distance for a permanent or semi-permanent settlement. There was no reason to assume that other springs nearby may have dried up. Other potential water storage features at the site were initially deemed unsuitable for year-round water storage because of their shape and size. This included a 6-meter deep funnel-shaped cistern with a considerable storage volume of 60 cubic meters, still used today to supply water to livestock. These were some of the key arguments made to support the interpretation that hunter-gatherers built this ancient megalithic site.

Instead, the researchers postulated that religion and monument-building may have been catalysts for early civilizations. This interpretation challenged the widely held idea of how hunter-gatherers transitioned to farming, creating food surpluses that, in turn, enabled the development of more sophisticated social structures. Sadly, this interpretation underestimated the site's importance as a potential early farming community.

Since then, more PPNA sites have been excavated, leading to insights that challenge the hunter-gatherer interpretation. This section provides an overview of the hydrogeological clues that indicate Göbekli Tepe may have hosted a semi-sedentary civilization.

In 2007 and 2009, intensive field investigations revealed 61 rock-cut, cistern-like structures. But were these structures naturally occurring limestone depressions or artificially created?

To resolve this, the researchers employed dynamic probing, which allowed them to measure the depths of the pits despite being filled with earth. Surprisingly, they found the pits were considerably deep, ranging from 2 to 5 meters, and were arranged in an ingenious pattern.

These structures were situated beneath their water catchment area and strategically positioned in a cascade-like formation beneath the plateau's edge. This configuration allowed water to collect in one pit and overflow into the next, creating an interconnected water storage system. The excavations also yielded channels carved into the bedrock, covered with limestone slabs — similar to our drainage systems today — which could have harvested rainwater.

The researchers concluded that the rock pits were cisterns, likely filled through surface water collection, such as rainwater harvesting, rather than sourced from underground water sources or natural springs. The cisterns at Göbekli Tepe are the oldest known facilities for drinking water. The channel-and-cistern clusters' strategic positioning and interconnectedness suggest a well-planned, site-wide approach to water conservation and utilization at Göbekli Tepe.

This approach supports the argument for a more permanent or semi-sedentary site occupation, as they demonstrate the inhabitants' ability to manage and store water resources over extended periods.

What else lies beneath?

While the water storage is an essential part of the puzzle, excavations have revealed further evidence of a semi-sedentary settlement at Göbekli Tepe.

The sprawl of excavation sites, the sheer number of structures unearthed, and their proximity to each other, with some sharing a wall, indicate that this was a settlement and that it might have been densely populated.

Archaeologists also emphasize that we should remember that a place of worship being separate from one’s home is a secular Western concept. People living in Göbekli Tepe 10,000 years ago may not have had that distinction. They may have worshipped and lived in the same place.

The detailed stone masonry in the form of corridors, portals, cornerstones, steps, plastered stone benches, and even flooring, as well as domestic artifacts such as limestone basins, grinding stones, hearths, and massive limestone vessels that may have been used to store grain and food, make it more likely that this was a semi-permanent settlement rather than a makeshift, nomadic one.

Radiocarbon dating of animal and human bone fragments is imprecise, as the collagen isn’t preserved well over time. Instead, researchers have had to rely on charcoal remnants as a proxy for dating when the site was settled and how long it persisted. The fill or mortar between buildings has also yielded pollen grains and seeds, which can be used as additional proxies to determine the duration of site occupation.

Suppose we can verify that a site was populated for a lengthy period and was developed in phases, as several constructions at Göbekli Tepe show, we can assume that the people were semi-sedentary rather than nomadic.

We should remember that only a fraction of the site has been excavated. One can only wonder what other clues we’ll unearth in the years ahead.

Do you enjoy tales from lost civilizations and cultures from the ancient world and the Middle Ages?

Share this story with your friends and family and subscribe to this newsletter.

If you wish to support the newsletter, consider opting for a paid membership or buying me a coffee!

While you are here, don’t forget to check out the Geosophy newsletter by Devayani.

References

Schmidt, Klaus (2011). “Göbekli Tepe: A Neolithic Site in Southwestern Anatolia”. In Steadman, Sharon R.; McMahon, Gregory (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000–323 BCE). Oxford University.

“Göbekli Tepe – Investigations into the extraction and use of water in the area of the Stone Age mountain sanctuary,” Richard A. Herrmann, Klaus Schmidt 2012.

Dietrich, L., Meister, J., Dietrich, O., Notroff, J., Kiep, J., Heeb, J., Beuger, A., & Schütt, B. (2019). Cereal processing at Early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Turkey. PLoS ONE, 14(5).

Banning, Edward B (2023). “Paradise Found or Common Sense Lost? Göbekli Tepe’s Last Decade as a Pre-Farming Cult Centre” Open Archaeology.

The Tepe Telegrams - News & Notes from the Göbekli Tepe Research Staff

Can almost imagine hunter gatherers slowly building sites like this that they return to periodically. Eventually they don't leave maybe? or maybe leave some people to take care of the farming and the rest go hunt. Then they get better and better at farming and they start doing less hunting. Then suddenly your religious site turned religious farming site turns into a little settlement. That is mostly my imagination but its really fun to ponder.

I recommend the Ancient Architects channel for regular vids on topics like this.

My sense from watching vids like this one and some reading, is that people lived at Gobelki tepe, Karahan tepe and other pre-pottery Neolithic sites in Anatolia and the Levant. The ring structures had roofs, and the site was pre-Agricultural in that the grains consumed were wild type. Full-fledged agriculture uses domesticated plants, which were not present. This does not preclude cultivation of wild plants for human consumption, but the abundance and variety of animal bones found shows that hunting was still very much a thing. Cultivation may have been one of a number of strategies for securing enough food to permit a sedentary lifestyle that permitted the construction and regular use of infrastructure like that seen at Gobekli tepe.