Who Were the White Huns?

Exploring the rise and the legacy of a forgotten power which tormented India and Persia during antiquity

In the mid-4th century AD, a storm from the Eurasian Steppes disrupted the tranquility of ancient civilizations. Ruthless warriors emerged from endless pastures and wreaked havoc on the proud empires of India and Persia.

They were the White Huns, a mysterious force that struck fear into the hearts of those who encountered them.

Where did they come from?

Were they related to Attila and his Huns?

Why were they called the "White" Huns?

These questions have long puzzled historians. Today's newsletter will explore the theories surrounding the White Huns' origins and legacy.

We’ll learn about the Kidarites and the Hepthalites, the most powerful White Hun dynasties, and how they shaped the future of two of Asia’s oldest civilizations.

So, without further delay, let’s dive into the fascinating world of the White Huns.

Reminder: By choosing a paid membership (just $5 a month or $50 annually), you're helping amplify voices that history books too often overlook. Your support means these stories get the attention they deserve.

You’ll gain access to tons of members-only content👇

Full-length deep dives into untold stories: no paywalls, no cuts.

The entire archive of amazing stories from the Ice Age to the Fall of the Mongol Empire, the hottest archaeological finds, and the appetizing history of food.

Early access to special editions—be the first to dive in.

Join lively discussions in members-only posts and subscriber chats.

Origins of the White Huns

The Huns were not an ethnic group like the Chinese, Indians, Persians, or Romans; they constituted a political order rather than an ethnicity. The order's origins can be traced back to the mighty Xiongnu Empire (3rd century BC–2nd century AD), which I briefly mentioned in a previous story about the origins of the Silk Road. I’ll do a detailed post in the future focusing on the Xiongnu.

Ancient Chinese sources indicate that the White Huns are descendants of the Xiongnu, a claim supported by archaeological and genetic evidence.

In 2019, Endre Neparáczki, a Hungarian geneticist, studied the DNA of 49 individuals from the Huns, Avars, and Magyars who occupied the Hungarian plains after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

He concluded that the Huns were a mixture of East and West Eurasian peoples, akin to the Xiongnu. While the Xiongnu nobility primarily comprised Turkic and Yeniseian groups, it also included Mongolian and Iranian speakers.

According to 6th-century Roman historian Procopius, the White Huns were ruled by a king who governed under a constitution. They most likely had a single ruler and several feudatories under him.

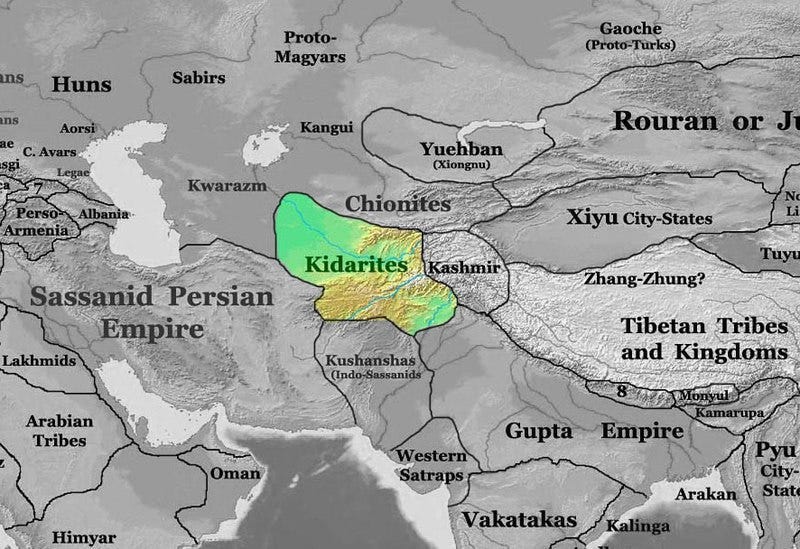

In the mid-4th century, one such White Hun feudatory, the Kidarites, led by Kidara I, invaded Central Asia.

The rise of the Kidarites

Before we discuss the exploits of the Kidarites, I am sure you are wondering, “Why are they called White Huns?”

Sanskrit texts referred to the Huns as “Sveta Huna,” meaning White Huns. Was white a reference to their skin tone?

Procopius thought so.

He interpreted "white" as referring to white-skinned people rather than those resembling the East Asian Huns of Attila. This interpretation, however, is incorrect.

In Hunnic society, white represented the western direction, black indicated the north, blue symbolized the east, and red signified the south. The black and blue Huns held a higher status than their red and white counterparts.

Attila's Huns, for example, used black.

Some scholars believe the Huns adopted their color codes from their Xiongnu ancestors. The Xiongnu may have adapted the directional color-coded system from the Han Empire.

Why did the White Huns invade Central Asia and later Persia and India?

While studying the Hunnic expansions, I have encountered several theories and debates surrounding this topic. Recent studies propose that the Hunnic expansion west of the Altai region may have started as early as the late third century.

This expansion occurred due to several factors, including military pressure from the Rouran Khaganate and radical climate deterioration in the Altai Mountains in the early fourth century.

The Rourans were proto-Mongolic people who emerged north of China in 330 and established a powerful Khaganate. They were the first people to use the title of Khan or Khagan as the head of the state, which later became standard practice among the Steppe Empires. If you’ve watched the movie Mulan (1998), the antagonists, referred to as “Huns,” led by Shan-Yu, are based on the Rourans.

Pressurized by the Rourans and a degrading climate, the Kidarites were among the first groups of White Huns to move from the Altai Mountains in search of new lands. The term Kidarite possibly referred to a westward direction of migration, deriving from the Old Turkic word Kidirti, which means west.

The Kidarites moved south in the 350s and absorbed the Kangju kingdom in the Tarim Basin region of present-day Xinjiang.

This invasion into the heartlands of Central Asia put pressure on Sassanid Persia’s eastern borders. Expanding into Central Asia meant the Kidarites captured the lucrative Silk Road trade from the Kushans, who were past their glory days. The Kushans were a nomadic people who controlled the Silk Road during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, ruling from Bactria, in present-day Uzbekistan, and later from Purushapura, near present-day Peshawar in Pakistan.

The Kidarite realm was now sandwiched between two powerful empires: the Persian Sassanid Empire to the west and the Indian Gupta Empire to the east. After cementing a strong foothold in Central Asia, the Huns eyed the riches of India.

Hunnic invasions of India

At the beginning of the 4th century, India was ruled by the Gupta Empire. Military campaigns led by Samudragupta( 335-375) and his son Chandragupta II( 380-415) united most of the Indian subcontinent under Gupta rule.

Towards the end of the 4th century, Chandragupta undertook a punitive expedition in Balkh, in present-day Afghanistan, to check the growing incursions of the Kidarites, who had conquered the Kabul Valley. The Gupta expedition was successful but proved to be a temporary deterrent.

During the reign of the Gupta monarch Skandagupta (455–467), the Kidarites grew bolder and launched attacks on India. The Bhitari pillar inscription, dating from the end of Skandagupta’s reign, describes how the Huns almost destroyed the Gupta state during the rule of Kumaragupta I, Skandagupta’s predecessor.

The inscriptions describe how Skandagupta had to re-establish his lineage ‘that had been made to totter’ and encounter many dangers and hardships that forced him even to ‘spend a night sleeping on the bare earth.’

Skandagupta then claims to have vanquished the Huns and conquered the universe. Despite the hyperbolic descriptions, most historians agree that the Guptas had thwarted the Huns, but unfortunately, it came at a price. The Guptas permanently lost their north-western territories.

The intrusion of another White Hunnic dynasty, the Hephthalites, into Kidarite territory allowed the Guptas a brief respite from the invasions. The Kidarites lost much of their domain to their Hepthalite cousins and retreated from India.

The declining Guptas were happy to see the Kidarites' power restricted. But now, a new threat loomed large.

They were the Alchon Huns, led by Toramana.

Toramana was a “sub-king” appointed by the Hephthalites to rule over India. He was the ruler of the Alchon Huns, a feudatory of the Hephthalites. By the end of the 5th century, he launched devastating raids deep into India.

Tormana conquered parts of Western, Northern, and Central India up to present-day Madhya Pradesh. Indian records describe the Hun warlord as the “boundlessly famed ruler of the earth.”

In 515, Prakashadharman, the ruler of the Central Indian Aulikara dynasty, checked Toramana’s advance in Malwa. The Huns suffered a devastating defeat, and Toramana died shortly after the battle.

But the Alchons weren’t done yet.

Toramana’s son Mihirakula claimed the former Gupta territories and wanted to finish the mission his father had started.

Mihirakula had converted to Hinduism and, like Toramana, wished to establish the Hun rule in India as the legitimate successor to the Guptas. We know this because Mihirkula and Toramana minted Gupta-style coins throughout their controlled territories.

Later Buddhist literature depicts Mihirakula as a “wicked, cruel ruler.” According to the famous Chinese Buddhist traveler Xuanzang, who visited India in the 7th century, Mihirakula was interested in Buddhism. But when the Buddhist priests sent a “lowly servant” to the king’s assembly, he was enraged and ordered the destruction of monasteries.

Modern historians question Mihirakula’s image as a Buddhist persecutor. These accounts were written centuries after Mihirakula's demise, and often, negative images of a ruler in Indian literature were related to the writer’s sect losing royal patronage.

It is easy to imagine Mihirakula, like other Huns, annihilating everyone who opposed him. I doubt if he specifically targeted Buddhists and spared others.

The soldiers of Mihirakula ravaged the Northern regions of India and marched toward Central India. But the Aulikaras were once again in the way of the Huns.

In 528, a coalition of Indian rulers commanded by the Aulikara king Yashodharman confronted the Huns at Sondani.

The arrows of the Huns rained down on Indian war elephants. But the Aulikara resolve couldn’t be shaken. Yashodharman’s soldiers withstood the barrage of arrows and broke through the Hunnic lines, hacking them mercilessly.

Mihirakula was vanquished. One inscription says, “The man(Mihirakula) who refused to bow his head to anybody but Shiva was humbled.”

After a century of warfare, the Hunnic raids in India stopped. Persia faced similar waves of attacks, with even more devastating long-term consequences.

Hunnic invasions of Persia

The Kidarites’ arrival in 350 AD forced Sassanian monarch Shapur II to abandon the siege of the Roman citadel of Nisbis to deal with the Hunnic menace.

This triggered an eight-year conflict with the Huns, which resulted in the Kidarites capturing Sassanid lands in the eastern part of the empire. Both sides agreed to an uneasy ceasefire.

The Kidarites defeated the Persians numerous times during the reign of Sassanian ruler Bahram IV (388–399). But as they expanded their influence into India and Persia, they faced an onslaught from their Hephthalite cousins.

By 450 AD, Sassanian ruler Yazdegard II had stopped paying tributes and had begun taking Kidarite land in modern-day Afghanistan. Yazdegard became overconfident with his recent triumphs and demanded that the Kidarites pay tribute to him.

You can probably guess what happened: war.

The result: Persians were crushed.

Again.

Even after being weakened, the Kidarites were powerful enough to defeat the Sassanids. But the Persians had the last laugh, though, with some help.

In 464 AD, after the Romans refused to assist Peroz, the Persian Emperor negotiated for peace with the Kidarite monarch Khunkhas. Peroz was supposed to send his sister to the Kidarite king as a bride, but he sent a woman of lower status instead.

Khunkhas, enraged, invited 300 Persian officers and had them slaughtered and maimed—the result: war.

But this time, Peroz had the Hephthalites on his side. The Kidarites were beaten, and a joint Hephthalite and Persian force sacked the Kidarite capital, Balaam (perhaps present-day Balkh).

The end of the Kidarite realm was a massive relief for Persia. However, the Sassanids soon faced an even more significant threat. The Hephthalites, who helped them defeat the Kidarites, would become a terrifying juggernaut, ultimately subjugating a proud ancient civilization.

The Hepthalites didn’t help the Sassanids defeat the Kidarites out of kindness; instead, they sought to control the lands held by their Hunnic cousins.

The Hephthalites captured the areas of the Persian Empire that were previously under the control of the Kidarites, forcing Peroz to mount a punitive expedition. The Hephthalites, led by Khushnavaz (also known as Akhshunwar), repulsed the Persian onslaught and captured Peroz.

The Persian ruler was obliged to pay a substantial ransom and send one of his sons as a hostage to the Hunnic court.

Peroz failed to learn his lesson. In 484, he launched another campaign against the Hephthalites, breaking the peace treaty he signed with Khushnavaz against the advice of his ministers.

The results were catastrophic this time. The Huns dug a ditch and hid it with shrubs. The Persian army fell into the ditch, and the Huns picked them apart from a distance.

There were no survivors. Peroz perished in the conflict, either slain during the battle or later died of hunger.

Following their victory, the Huns conquered the Persian cities of Herat and Merv, as well as the entire eastern Persian province of Khorasan. They meddled in Persian politics, reducing the Sassanid ruler to vassalage and forcing him to pay tribute to the Huns until the 550s.

Chinese sources, such as Liangshu and Bei Shi, list Persia among the Hunnic domains, along with Kashmir, Sogdia, Khotan, Karashahr, and Kashgar. Thus, the Hephthalites controlled the world’s largest empire at the start of the sixth century. They ruled from Mesopotamia and Syria in the west to the Tarim Basin in the east and Central India in the south.

The decline of the White Huns and their legacy

In 552, Bumin led the Göktürks to revolt against the Rourans and established the First Turkic Khaganate. The Rourans were chased out of their homeland and took refuge in the Hephthalite realm.

The Turkic Khaganate expanded rapidly and allied with the Persians, who were tired of Hephthalite domination. The Turks were unhappy with the Huns for shielding the Rourans and, hence, found common cause with the Sassanids.

Bumin’s brother Istami, who ruled over the western part of the Turkic Khaganate, took Tashkent. The Turco-Persian alliance besieged Bukhara, the capital of the Hephthalites. In a tremendous eight-day battle, Hephthalites, led by King Gatfar, defended the city valiantly.

Despite Gatfar’s heroics, the Huns were defeated, and Bukhara was sacked. Between 560 and 563, the last Hephthalite king surrendered to the Sassanid ruler Khusrau, ending the reign of the White Huns.

Remember how the Persians enlisted the support of the Hephthalites to defeat the Kidarites, only to have the Huns turn on them? You’d be correct if you predicted that this would happen again.

Göktürks and Persians clashed.

The Turks conquered the territory inhabited by the Huns and began intermingling with them. Since the early 7th century, historians have struggled to distinguish between the "Turks" and the "Huns" in the regions formerly controlled by the Hephthalites. This blend of Turkic and Hunnic monarchs continued the legacy of the Hephthalite state.

![Probable Hepthalite rulers of Tokharistan, with single-lapel caftan and single-crescent crown, in the lateral row of dignitaries next to the Sun God.[35][36][32] Probable Hepthalite rulers of Tokharistan, with single-lapel caftan and single-crescent crown, in the lateral row of dignitaries next to the Sun God.[35][36][32]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!5QzM!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fde3a1273-217b-4d8a-a7e1-0ce81bf9152e_800x653.jpeg)

The most famous contribution of the descendants of the Hephthalites, which you are likely familiar with, was the monumental Bamiyan Buddha statues, built between 570 and 618. The construction of these magnificent sculptures was sponsored by the Hephthalite rulers of Tokharistan, also known as Bactria, which encompasses parts of Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. Before succumbing to the Taliban in 2001, these shrines endured generations of destruction attempts.

The successors of the Hephthalites put up stiff resistance against Arab invasions and the spread of Islam in Central Asia. The Nezak Huns and the Turk Shahi dynasty of Afghanistan, descendants of Hephthalites, pushed back the advance of the early Islamic Caliphates.

In the 650s, Arabs conquered Sistan and began making inroads into Kabul. But a Turk Shahi counter-attack proved lethal. The Turk Shahis forced the Muslims to flee Kabul.

In the 690s, the Arabs attempted another invasion but were defeated. Yazid bin Ziyad, the Muslim general leading the mission, died while trying to take Zabulistan. By the early 8th century, Afghanistan had become free from Arab influence, and the Turk Shahis had emerged as the leading power in the region.

The Turk Shahis maintained the traditions of their ancestors by being tolerant of various faiths, including Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. Although we have limited information about the original religion of the Huns, they adopted local beliefs in Central Asia, Persia, and India, allowing a syncretic culture to thrive.

Attila is usually the first name that springs to mind when we think about the Huns. But his cousins in Inner Asia, the White Huns, were equally extraordinary.

Through their conquests in India and Persia, they made a lasting impression, showing their military power and capacity for state-building. But their story isn’t just one of war and conquest. Along the Silk Road, they promoted religious and cultural tolerance, acting as bridge builders between Central and South Asian civilizations.

Their support for constructing the breathtaking Bamiyan Buddhas in the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan is a prime example.

Though the White Huns disappeared and merged into the civilizations they formerly controlled, their impact endures. It reverberates in the art, architecture, and histories of the places they ruled. Unfortunately, future generations won’t be able to witness the Bamiyan Buddhas, but those who saw them can thank these enigmatic warriors from the Steppes.

Do you love exploring the mysteries of lost civilizations and the rich cultures of the ancient world?

Share this story with friends and family, and don’t forget to subscribe to this newsletter for more fascinating insights!

If you enjoyed this story and would love to read more such stories, please upgrade to a paid membership.

References

R. C. Majumdar (1981). A Comprehensive History of India. Vol. 3, Part I: A.D. 300–985. Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House.

D. K. Ganguly (1987). The Imperial Guptas and Their Times.

Shoshin Kuwayama, “The Hephthalites in Tokharistan and Gandhara — Part 1,” Lahore Museum Bulletin 5.1 (1992), p. 4 translated by University of Washington

Livinsky, B.A. (1996). “The Hephthalite Empire”. History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III: The Crossroads of Civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Paris: UNESCO

Heirman, Ann; Bumbacher, Stephan Peter (2007). The Spread of Buddhism. BRILL. p. 88.

Kim, Hyun-Jin (2015) The Huns, Routledge.

Frankopan, Peter(2015) The Silk Roads : A New History of the World, Bloomsbury

Neparáczki, E., Maróti, Z., Kalmár, T., Maár, K., Nagy, I., Latinovics, D., Kustár, Á., Pálfi, G., Molnár, E., Marcsik, A., Balogh, C., Lőrinczy, G., Gál, S. S., Tomka, P., Kovacsóczy, B., Kovács, L., Raskó, I., & Török, T. (2019). Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1-12.

Jan, Changez (2022). Forgotten Kings: The Story of the Hindu Sahi Dynasty. Simon and Schuster

Fascinating story, I was familiar with the European Huns, but not so much with the White Huns. Comparatively speaking, the White Huns were probably as powerful as Attila's Huns, but built a more durable empire.

Mihirkula is said to be responsible for destruction of Takshashila.

Is Mihirkula is actual name Or translation of his Hunnic name into Sanskrit.

It would be interesting to know more about conversion of Huns to Hinduism.