When Buddha Met Hercules On The Silk Road

The Kushan Empire blended Greek and Indian art styles

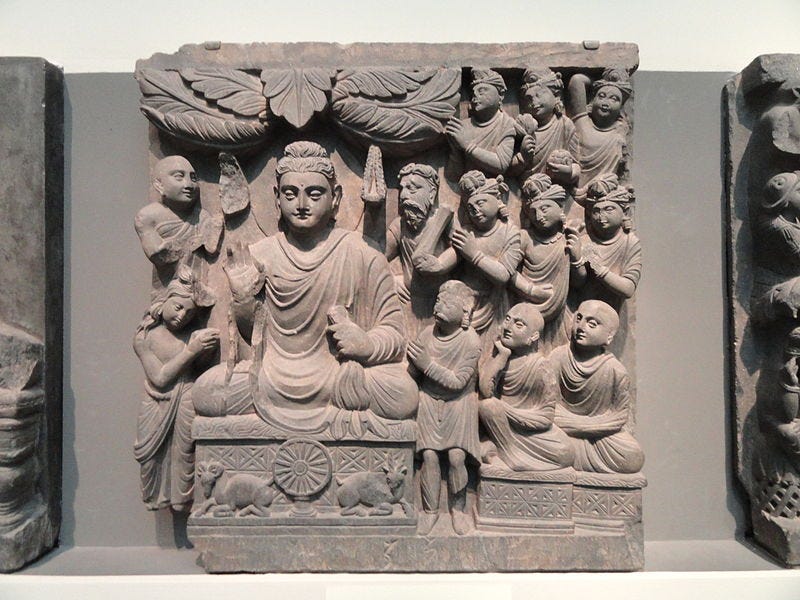

In 2008, during my first trip to Washington, D.C., I had the opportunity to visit the National Museum of Asian Art. There’s a gallery on Buddhist iconography. One of the panels titled “The First Sermon at the Deer Park in Sarnath” shows the Buddha seated beneath a tree, surrounded by devotees. He wears a robe that looks like a toga. Some of the people around the Buddha are dressed in distinctive Greek attire.

This panel is unique. It is one of the earliest depictions of Buddha in human form. The style is Gandhara art, which dates back to the second and third centuries and incorporates Indian and Greco-Roman elements.

Reliefs of Gandhara art can be found worldwide. I’ve seen them in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Indian Museum. The patrons of this artwork were the Kushans. They were one of the five ruling clans of the Yuezhi, a nomadic people whose origins can be traced to China's Gansu province.

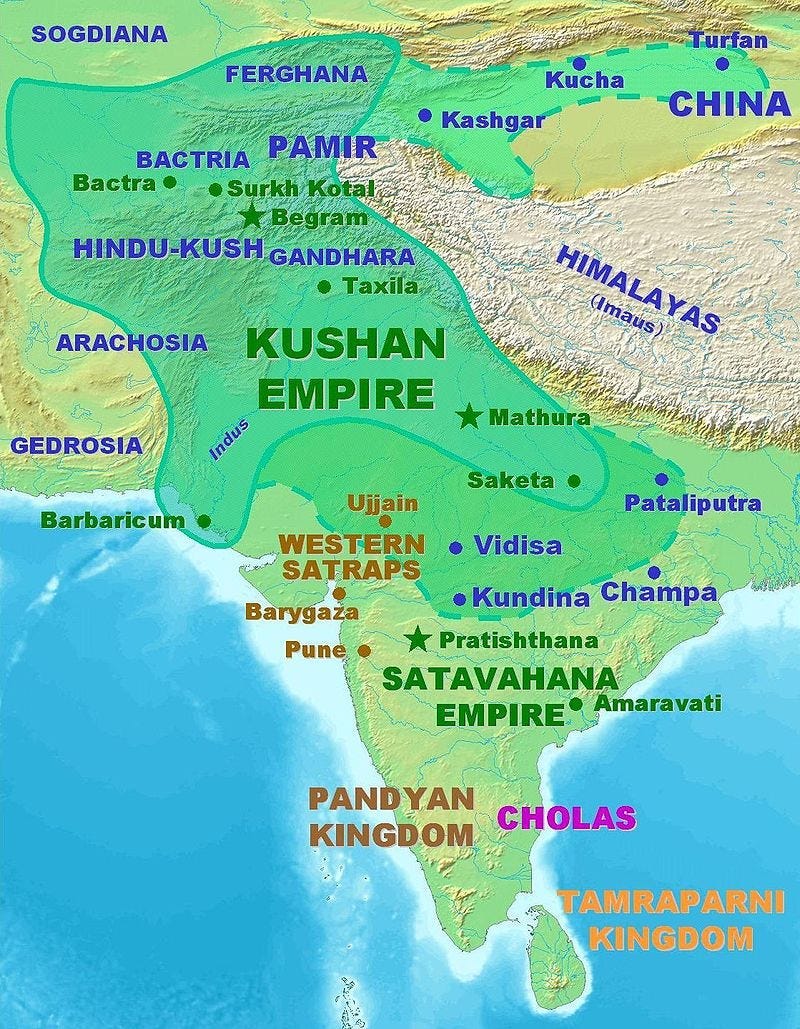

The Kushans ruled over a multiethnic empire in Central Asia, where cultural interactions brought together Eastern and Western art traditions. Their goal of making Buddhism appealing to the masses resulted in the religion becoming a global faith. They also played a pivotal role in expanding the Silk Road.

The Kushans are still a mystery, even though they established a mighty empire. Today, we’ll learn about their origins, rise to power, and patronage of Gandhara art. But before we discuss how the Kushans impacted our history, let’s find out why they migrated over 2,000 miles from China to Central Asia.

The Yuezhi Migrations

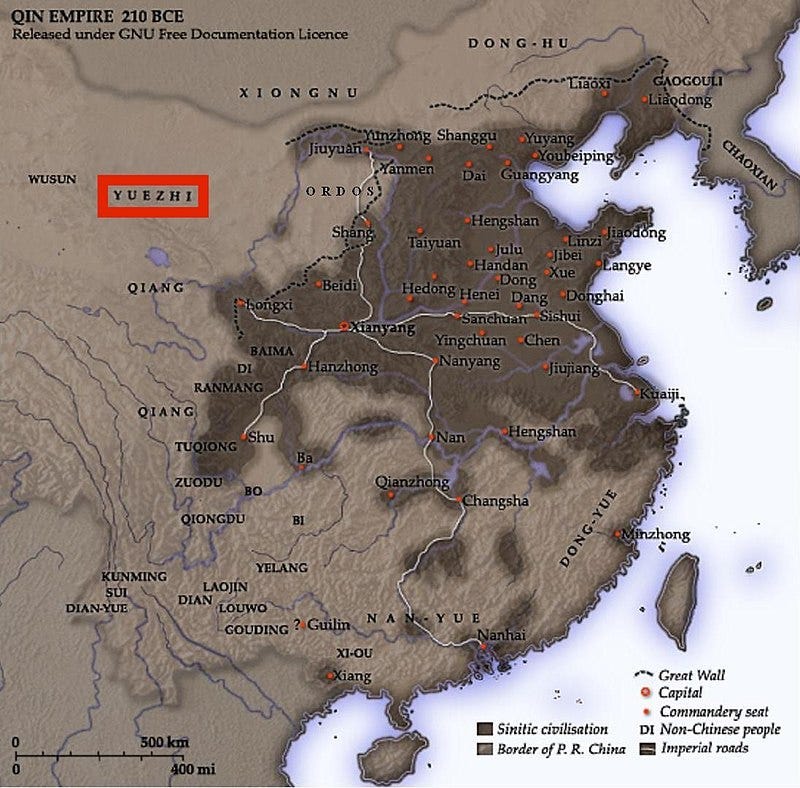

The Yuezhi’s origins are hotly debated, with most recent researchers believing they were Tocharians. Tocharian was an Indo-European language spoken in China’s Tarim Basin region until its extinction in the ninth century.

The Yuezhi were close allies of the Qin dynasty(221 BC to 206 BC), which unified China. They became influential by supplying horses to the Qin and trading with them. The Yuezhi’s primary adversaries were the Xiongnu, a nomadic people from Mongolia. To thwart the Xiongnu threat, the Tocharians and the Chinese joined forces and pushed them beyond the Ordos region in Inner Mongolia.

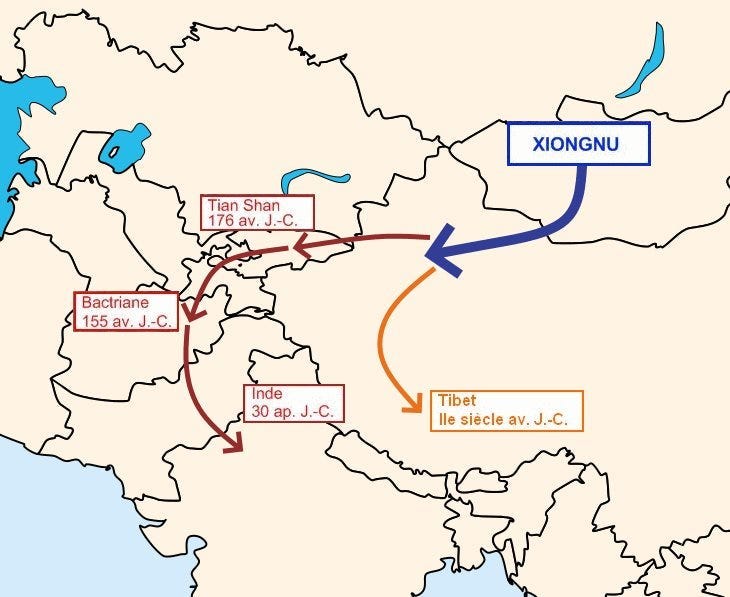

Modu Chanyu, a charismatic Xiongnu leader, captured power in 209 BC after assassinating his father, Touman. His prime target was the Yuezhi, who held him hostage during childhood. He defeated them and boasted his victory in a letter to the Chinese Emperor in 174 BC.

But the Yuezhi were far from finished. They were still in their homeland. Modu’s son Jiyu( reign 174 BC to 166 BC) dealt the Yuezhi a crushing defeat and evicted them from the Gansu region. The Yuezhi king was killed, and according to Sima Qian, his skull was turned into a drinking cup.

Defeated and out of options, the Tocharians migrated west and arrived in Kazakhstan’s Ili River Valley. There, they met the Sakas, a nomadic eastern Iranian tribe. The Yuezhi proved a formidable opponent for the Sakas, driving them south towards the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, based in present-day Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan.

If you’re wondering what Greeks were doing in Central Asia, I'll cover that later; for now, let’s continue our journey with the Yuezhi.

The Yuezhi lived temporarily in the Illi River valley. Their former neighbors and enemies, the Wusun, cut short their stay. The Wusun (meaning grandson of the crow) were an Indo-European nomadic people who were rivals of the Xiongnu and the Yuezhi. But after Modu Chanyu’s rise, they submitted to the Xiongnu, hoping to maintain their regional autonomy.

In 132 BC, the Wusun, with the help of their Xiongnu overlords, routed the Yuezhi and drove them from the Ili River Valley. Like the Saka, the Yuezhi were forced to migrate south.

The Tocharians entered the crumbling Greco-Bactrian kingdom, devastated by the Sakas. The Yuezhi had no trouble taking over this once-prosperous but now-fading Central Asian power. By 126 BC, they were well-established in Bactria, moving to a more settled lifestyle. The Kushans also expanded on the fortifications the Greeks and Parthians had built in Central Asia. Forts in Uzbekistan, such as Kamir Tepe and Ayaz Kala, and Surkh Kotal in Afghanistan show signs of monumental constructions during the Kushan rule.

The Chinese hadn’t forgotten about their nomadic allies. Seeking help to fight the Xiongnu, Emperor Han Wudi sent a delegation led by Zhang Qian to locate the Yuezhi and form an alliance.

Unfortunately for Zhang Qian, the Tocharians enjoyed their new wealthy lands and had no interest in fighting the Xiongnu. But don’t let the Yuezhi’s refusal to lock horns with their arch-nemesis deceive you. They had an appetite for conquest. To the south and the east were wealthy cities of the Silk Road, and being a historic mercantile community, the Kushans knew the potential of controlling this route.

Rise of the Kushan Empire

According to Chinese texts from the first century BC, the Yuezhi were divided into five ruling clans, each led by a yabghu (a Turkic title equal to the viceroy). The yabghus produced coinage in their name and ruled over sub-domains. In the first century, Heraios, a yabghu of the Kushan clan, seized control and defeated the other Yuezhi yabghus. We know little about Heraios besides his silver coins with Greek inscriptions.

His successor, Kujula Kadphises (reign 30–80 AD), consolidated authority and expanded the Kushan lands. Kadphises was the first of seven Kushan rulers identified by historians.

In 1993, a British humanitarian worker in Afghanistan saw Afghan rebels digging a trench on an artificial hill. The worker photographed the scene and sent the pictures to the British Museum. One photo captured the museum’s attention. The image was of a stone with text in Bactrian and Greek. The rock was the Rabatak inscription, which contained the genealogy of four Kushan rulers.

It was composed by Kanishka (reign 127–153 AD), the most well-known Kushan Emperor.

N. Sims-Williams and J. Cribb, who deciphered the Rabatak inscription, describe Kanishka’s lineage:

for King Kujula Kadphises (his) great grandfather, and for King Vima Taktu (his) grandfather, and for King Vima Kadphises (his) father, and *also for himself, King Kanishka

Kujula Kadphises extended the Kushan rule to the Kabul Valley, controlling the lucrative trade route connecting India and Central Asia. His son, Vima Takto, continued expanding east and attacked the Indo-Parthian Kingdom, which ruled present-day Pakistan and parts of Northern India.

According to the Book of Han:

His( Kujula Kadphises) son, Yan Gaozhen (Vima Taktu),15 became king in his place. He returned and defeated Tianzhu (Northwestern India) and installed a General to supervise and lead it. The Yuezhi then became extremely rich. All the kingdoms call [their king] the Guishuang (Kushan) king, but the Han call them by their original name, Da Yuezhi.

The conquest of northwestern India provided access to elephants, rhinoceroses, turtle shells, gold, silver, copper, iron, lead, and tin, making the Kushans wealthy.

Vima Kadphises, Vima Takto’s successor, invaded the Indian heartland, deposing the Indo-Scythians at Mathura. His son, Kanishka, continued expanding deep into eastern and central India. According to the Rabatak inscription, Kanishka controlled a vast territory stretching from present-day Uzbekistan in the west to Pataliputra in east India, the former Mauryan capital.

Kanishka was known not just for his conquests but also for his patronage of Buddhism.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Forgotten Footprints to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.