Was the Buddha a Scythian?

Why the Buddha-Scythian Connection Doesn’t Hold Up

Could the spiritual figurehead of Buddhism, the Buddha, trace his lineage back to the fierce Scythian nomads who once dominated Eurasia during the early Iron Age?

At first glance, this idea seems like a wild social media conspiracy. Yet, when I dived deeper, I discovered that this theory has intrigued scholars for decades.

Traditional accounts tell us that Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, was born in the Indian subcontinent around the 6th or 5th century BC in a region near the present-day Nepal-India border. He hailed from a tribe called the Sakyas, earning him the title Sakyamuni, which means "Sage of the Sakyas."

But how does this tie him to the Scythians, renowned for their horsemanship and conquests? The connection lies in the name of the Buddha's clan: the Sakyas. Some scholars propose that Sakya may be linguistically linked to "Saka," the term for Scythians in Iranian and Sanskrit literature.

Could this hint at an ancestral link?

What evidence do we have to support this hypothesis?

Before discussing the validity of these theories, let's learn briefly about the Scythians and their legacy.

What's in a name? The true meaning of Sakya

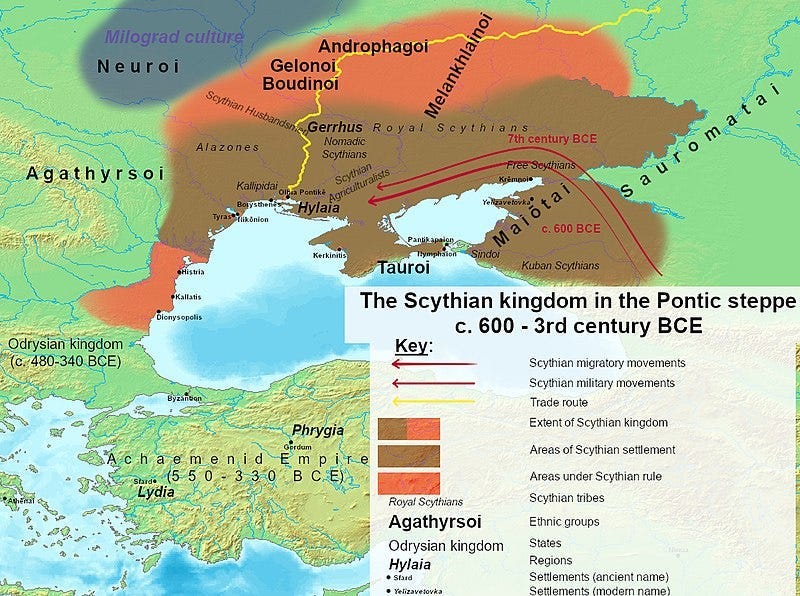

The Scythians were an ancient nomadic people who lived in the Eurasian Steppe from around the 9th century BC to the 4th century AD. They are known for their exceptional horsemanship and mastery of archery. They were organized into clans or tribes, each with its chieftain. Scythians were skilled warriors who frequently fought with rival tribes, and neighboring settled civilizations.

The Scythians were famous for their art, particularly their intricate gold jewelry and metalwork. They left no written record of their history, so much of what we know about them comes from the accounts of ancient Greek, Persian, and Chinese sources. We are certain that the Scythians spoke Iranian languages.

The Persians referred to them as Saka, a term we also find in Sanskrit sources. Modern scholars debate whether Saka refers to all Scythians or a particular tribe of Scythians living in Central Asia, north of Iran, and present-day Afghanistan. However, scholars agree that the Sakas were Scythians and were Iranian-speaking.

Scholars who propose the Buddha had Scythian origins suggest the Scythians moved from Central Asia and settled in the foothills of the Himalayas.

Sanskrit texts from the Early Vedic age (1700 BC to 1000 BC) do not mention the Sakyas, leading some historians to believe They must have arrived in India in the Later Vedic age (between 1000 and 500 BC). Buddha and his ancestors were born during this period, so Sanskrit texts of the Later Vedic era mention the Sakyas.

Historians who favor Buddha’s Iranian origin say that the terms “Sakya” and “Saka” sound similar, which is no coincidence. Both have the same root, sak, which means “competent or strong.”

The Ambattha Sutta, a Theravada Buddhist text, suggests that the Sakyas were fierce, harsh, touchy, and argumentative. This description matches Herodotus’s of the Scythian nomads the Greeks encountered.

But are similar-sounding names and characteristics enough to conclude Sakas and Sakyas were the same people?

Some linguists disagree about the origin of the term Sakya. They say Sakya is derived from the Sak tree, either the teak tree or the Sal tree. Since Sal is native to the Himalayan region, unlike teak, the chances are that “Sak” refers to the Sal tree, and the term Sakya comes from the Sanskrit term for a branch, Shakha.

Buddhists revere trees. Buddha achieved enlightenment under the Mahabodhi tree, which was a sacred fig tree. Could the Sakyas get their name from the Sal tree’s branches?

Maybe.

Another problem is drawing conclusions based on the similarities between the terms Saka and Sakya. Sanskrit sources, such as the inscriptions of the Mathura lion capital, document the arrival and rule of the Sakas, also known as the Indo-Scythians, from the 2nd century BC onwards.

Several coins of Saka rulers are found all over Northern India, present-day Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Sakas are mentioned in versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata around the 2nd century AD.

Indian sources call the Sakas “barbarians.” The Satavahanas, a dynasty based in the Deccan region of India under Gautamiputra Satakarni, clashed with Sakas ruling the Western regions of India. The Satavahanas prevailed. Satakarni commemorated a Hindu calendar in 78 AD to mark his victory over the Sakas, and we call the epoch the Saka era.

This begs the question: If Sanskrit sources talk extensively about Sakas, why would they be silent about their arrival a few centuries ago?

It makes little sense to me, but we should hear all sides of an argument before concluding.

Scholars who support Buddha’s Scythian origins propose several theories to support their hypothesis.

Let’s look at them and see how solid the proof of an Iranian Buddha is.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Forgotten Footprints to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.