The Origins of the Pork Taboo

Exploring why one-third of humanity doesn’t consume pork

Pork is divisive.

With 36% of humanity eating pigs, it is the most widely consumed meat on the planet. Yet, almost a third of the world’s population doesn’t eat pork.

The reason behind not eating pork is often a religious taboo. Pork is forbidden in Islam and Judaism. Many Christian sects, such as the Seventh-Day Adventists, abstain from eating pig meat. Pork is not popular among Hindus, although there is no official religious restriction.

Have you ever wondered why Judaism and Islam prohibit pork? Many foods are forbidden in the two religions, yet several of their followers don’t practice them. But why do Muslims and Jews follow religious guidelines on pork?

Scholars researching the pork taboo provide several theories about its origins. We’ll analyze some of the more popular ones to determine the best possible explanations.

But, before we get into the reasons behind the ban, let’s go over what archaeologists Brian Hesse and Paula Wapnish refer to as “pig principles.”

The pig principles are a set of observations about pigs that will serve as a groundwork for understanding the origins of the pork taboo. The scholars have proposed several principles. We’ll talk about the most relevant ones.

But first, let us briefly review the history of pig domestication.

Reminder: By choosing a paid membership (just $5 a month or $50 annually), you're helping amplify voices that history books too often overlook. Your support means these stories get the attention they deserve.

For a limited time, till September 25th, you will receive 20% off all subscriptions (just $4 per month and $40 per year), for life!

You’ll gain access to tons of members-only content👇

Full-length deep dives into untold stories: no paywalls, no cuts.

The entire archive of amazing stories from the Ice Age to the Fall of the Mongol Empire, the hottest archaeological finds, and the appetizing history of food.

Early access to special editions—be the first to dive in.

Join lively discussions in members-only posts and subscriber chats.

History of Pig Domestication and the Pig Principles

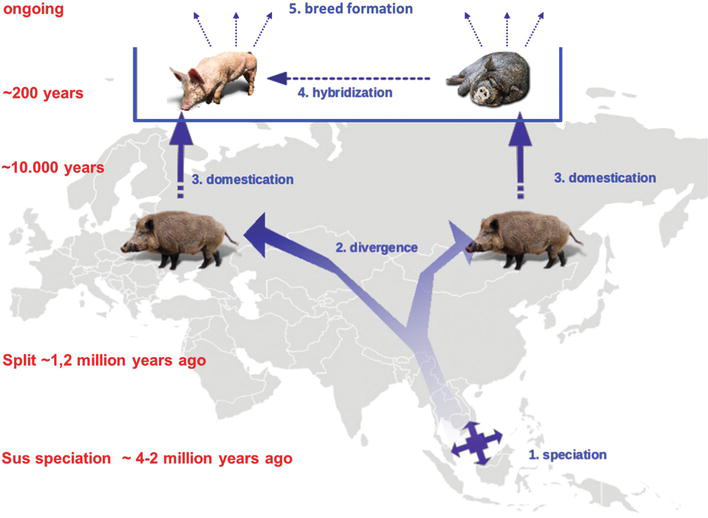

The history of the domestic pig traces back to its ancestor, the wild boar (Sus scrofa), which originated in Southeast Asia over five million years ago before spreading across Asia and Europe. Humans hunted these intelligent creatures for millennia, and around 10,000 years ago, in both the Near East and later in China, the process of domestication began, gradually shaping S. scrofa into S. scrofa domesticus (pig).

Archaeological evidence from Hallan Çemi in southeastern Anatolia, dating around 10,000 BC, revealed that nearly one-fifth of animal remains were boar bones. Most of these were from young animals, implying intentional hunting strategies that favored herd management.

There are numerous depictions of boars at Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites such as Göbekli Tepe, highlighting the creature’s importance during the transition from hunter-gatherer society towards a sedentary lifestyle.

According to Melinda Zeder of the Smithsonian, permanent human settlements and cultivated fields attracted boars, giving hunters the chance to selectively cull young males while sparing breeding females, encouraging herd control.

At Çayönü in Anatolia, where humans settled around 8600 BC, excavations revealed boar remains that were smaller and younger than those of earlier populations, showing signs of early physical changes linked to domestication.

Clear evidence of domesticated pigs was found at Tel Motza, near Jerusalem, with bones dating to just after 7000 BC that display traits of domestication: smaller body size, shorter snouts, and more docile temperaments. Subsequent discoveries across the region confirm the spread of the domestic pig.

A pig-shaped figurine found at Tell Mozan in Syria, from the third millennium BC, suggests pigs had already taken on features distinct from wild boars.

Unlike sheep and goats, pigs spread more slowly due to their dependence on environments rich in water and forests for foraging. Still, they offered early farming communities significant benefits: abundant meat and the ability to consume waste, contributing to improved hygiene in densely packed human settlements.

Archaeological findings indicate pigs also had a social and religious role. At various Neolithic sites across the Near East, caches of pig bones suggest they were slaughtered for communal feasts that reinforced social bonds.

At Ain Ghazal in Jordan (7200 BC–5000 BC), archaeologists found pig skulls buried alongside human remains, hinting that the mammal had ritual or symbolic value in addition to being a food source.

Based on the analysis of historical and archaeological data spanning thousands of years in the Near East, Hesse and Wapnish outlined the following pig principles:

Pigs breed rapidly, and a large herd can be formed from just a few starter animals.

Pigs do not produce byproducts such as wool or dairy. Secondary animal products were critical for long-distance trade and taxation during the Bronze Age. This made pigs less appealing for wealth generation than ruminants.

Pigs do not move as fast as sheep, cattle, goats, horses, and camels. Because of this, nomadic pastoralists who travel vast distances choose not to breed pigs.

Pigs are less expensive to raise than ruminants since they don’t require grazing. Hence, pig farming is common among lower socioeconomic classes.

Because of their rapid reproduction and variable litter sizes, pigs are difficult to tax.

Pigs carry diseases that can be transmitted to humans, such as tapeworm and trichinosis.

Keeping the above pig principles in mind, archaeologists have investigated several theories for the genesis of the pork taboo. Let us determine the most plausible explanation for the origin and sustenance of one of history’s longest-running dietary restrictions.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Forgotten Footprints to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.