The Mystery of Cahokia’s Mounds: America’s Lost Ancient City

The rise and fall of the largest pre-Columbian metropolis north of Mexico

Welcome to a special edition of Forgotten Footprints!

Today, I’m joined by

from in search of the magnificent Mississippian metropolis of Cahokia. Long-time readers of this newsletter will recall Jon, who retired as a Professor of History at the New Mexico State University and was the Director of the New Mexico History Museum. He has previously contributed to Forgotten Footprints, sharing his visit to Alaska and exploring the lives of the First Americans.Jon and I will discuss the origins of mound-building in North America, the factors contributing to the rise of Cahokia, what made the city such a grand spectacle, why people from all over America migrated there, and what led to its eventual decline.

Let’s dive in!

Sailing Down the Mississippi

When we think of pre-Columbian North America, we don't imagine large urban centers north of Mexico. Centuries before Columbus arrived, a mega-metropolis thrived near modern St. Louis, Missouri. On the eastern banks of the Mississippi River in southern Illinois lie the ruins of Cahokia, the largest pre-contact city built north of the Rio Grande River.

In its heyday, in the 11th century, it boasted a population of 10,000-20,000 inhabitants, comparable to London and Paris during that era. What distinguished Cahokia from other renowned cities of the world?

Congressman Henry M. Brackenridge, an amateur historian, lawyer, and friend of Thomas Jefferson, visited St. Louis in 1811. He discovered over 100 mounds where Cahokia formerly existed.

Awestruck, Brackenridge commented:

“I was struck with a degree of astonishment, not unlike that which is experienced in contemplating the Egyptian pyramids. What a stupendous pile of earth! To heap up such a mass must have required years and the labors of thousands.”

In a letter to Jefferson, Brackenridge was the first Euro-American to admit that an enormous city rivaling those of the Aztecs and Mayans existed near St. Louis. The media astonishingly ignored his report. The lack of awareness about the existence of a grand ancient city built by the Indigenous people of America resulted in unchecked construction, causing damage to many of Cahokia's structures.

Excavations since the 1960s have revealed that Cahokia was a thriving city with plazas, causeways, and 120 massive mounds. Among the surviving mounds, Monks Mound was the largest, covering an area greater than the pyramids at Giza.

What did these enigmatic structures represent? How did a city rise on Mississippi's floodplains?

To get the answers, let’s discover who built the city and why they were drawn to the area. Before traveling to Cahokia, we’ll briefly review the history of mound-building in America and what they teach us about the communities that built them.

America’s First Mound Builders

Before we begin our search for the moundbuilders of Cahokia, it is vital to remember that the city we call Cahokia was named after the Cahokian tribe. These Algonquian-speaking Native Americans moved to the area in the 17th century, several centuries after the Mississippian metropolis collapsed. They were not related to Cahokia's founders. Nobody knows what the mysterious moundbuilders called themselves because they didn't leave any written records.

In the absence of documentation, we begin our search for the origins of the mound-building in Northeastern Louisiana on a hill overlooking the Ouachita River. Around 3500 BC, Indigenous people built eleven irregularly shaped mounds connected by a ridge, the largest of which was roughly two stories tall. These mounds, known as the Ouachita Mounds, were built long before the advent of agriculture in North America. The discovery of Ouachita Mounds cast doubt on the idea that hunter-gatherers could not create elaborate structures and lacked social hierarchy.

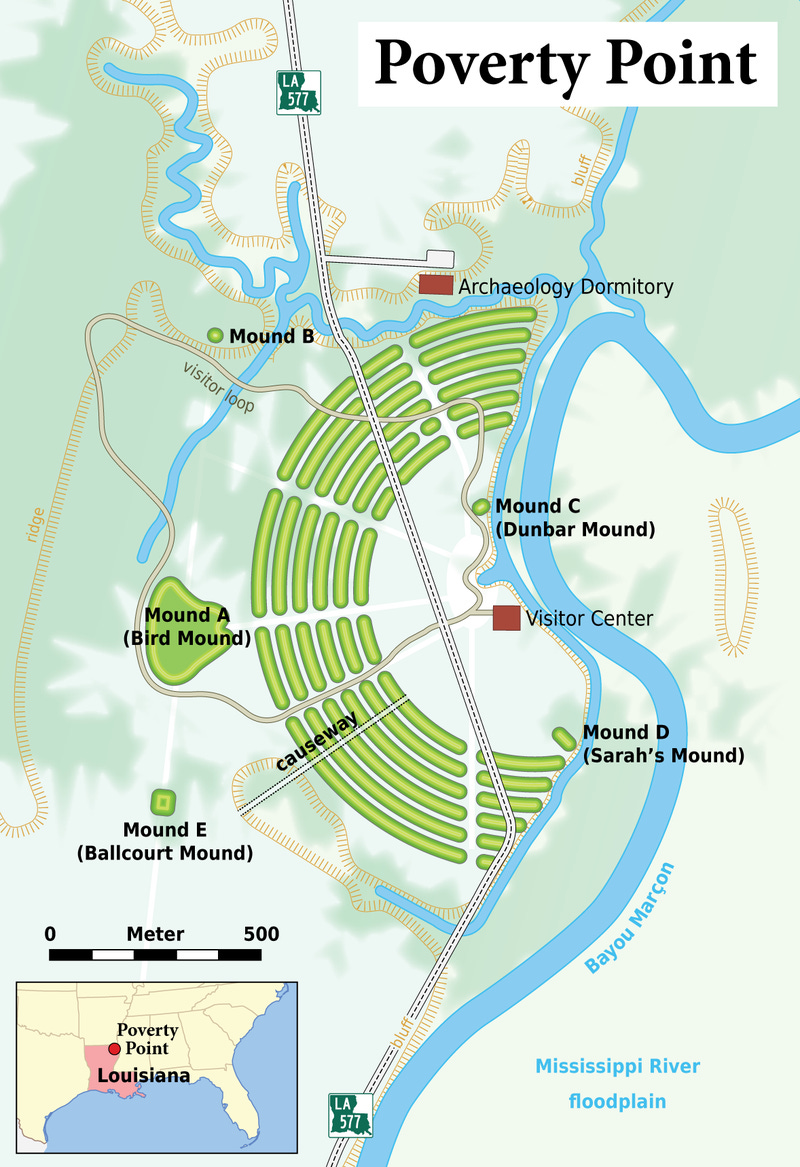

After the Ouachita, there is a millennia-long hiatus before mounds appear at Poverty Point, Louisiana.

Poverty Point, 55 kilometers from Ouachita, has earthen ridges and mounds erected between 1700 and 1100 BC. The construction resembles an amphitheater, with six concentric C-shaped ridges, each five feet tall. The ends of the widest C-shaped ridge are 3950 feet apart, and it wasn't until the 1950s that archaeologists discovered they were structures thanks to aerial photography.

The subsequent evidence of mound-building appears seven hundred years later in the Ohio Valley, where the Adena Culture flourished between 800 BC and 100 BC. The Adena mounds served as tombs, much like the kurgans of the Eurasian Steppes, and grave goods such as copper beads, bracelets, stone tablets, textiles, and stone tobacco pipes were uncovered.

Agriculture flourished across America during this period, spurring Adena's cultural expansion across the Midwest into Indiana and Kentucky and to the east as far as Vermont. Following the demise of the Adena culture, the Hopewell Culture, also centered in Ohio, emerged as America’s next prominent mound-building civilization.

Hopewell may have been a later stage of Adena, thriving between 100 BC and 400 AD. The culture, named after the farmer on whose land the first site was unearthed, was one of North America's most prominent pre-Columbian civilizations. Its greatest extent was from the northern borders of Lake Ontario to Crystal River, Florida, in the south.

The Hopewell Culture's most notable characteristic was earthwork mounds. These earthworks were of various geometric shapes, with square, rectangular, and circular being the most popular. The Hopewell Culture National Historical Park contains 23 earthen mounds. Inside each mound is a charnel house containing the deceased's remains. After someone died, the Hopewell people cremated the body, torched the charnel house, and then constructed a mound over it.

During the Hopewell period, we see a crystallization of social hierarchies germinating in the Adena culture. Some academics argue that a hereditary elite class may have evolved at Hopewell, dominating society and driving large-scale construction projects.

Mound building was a joyous occasion that brought the community together. The elaborate procedures for decorating the tombs of the dead and creating complicated geometric designs for mounds necessitated a tremendous commitment of time and resources, overseen by charismatic leaders.

The establishment of a new hierarchical elite in the Midwest and Eastern United States was intimately related to the spread of religion and provided the groundwork for Cahokia's rise centuries later.

Big Bang: The Birth of Cahokia

St. Louis sits at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. The area is a floodplain blessed with abundant natural resources, known as the American Bottom. The river system is ideal for the movement of people and goods.

Around 600 AD, several small agricultural settlements arose in the American Bottom. These communities supplemented their diet with hunting, fishing, and foraging. These groups were pretty insular, and there wasn’t much interaction among them.

Around 900 AD, maize was introduced to the region from Mesoamerica, boosting food production. A single corn kernel produced a plant that yielded hundreds of seeds, allowing a farmer to produce enough maize on a small plot to feed a family or on large fields to feed a city.

But corn has a hard time naturally propagating. Its kernels are securely attached to a cob and enclosed inside a tough husk, requiring humans or animals to tear into the external covering to release the seeds.

As author Charles Mann says in his book 1491:

“Modern maize was the outcome of a bold act of conscious biological manipulation—‘arguably man’s first, and perhaps his greatest, feat of genetic engineering.’”

Humanity’s first Genetically Modified Organism(GMO), maize, revolutionized farming throughout the Americas. In addition to maize, the Mississippians also grew beans and squash. The Three Sisters of Native agriculture—corn, beans, and squash—are still a mainstay of First Nations today.

By the 10th and early 11th centuries, a few thousand people lived in small villages in a 2500 square mile area in the American Bottom. They grew crops during summer and stored them for winter. Religious festivities were closely connected to the harvesting season. Neighboring communities probably gathered together to share common resources, resolve territorial disputes, and mourn the passing of village elders.

And then something unique happened in 1050.

A new societal order emerged, with Cahokia growing from a few thousand individuals to a city of over 10,000 people in a matter of decades. Archaeologist Timothy R. Pauketat of the University of Illinois refers to this sudden unexplained population growth and the formation of a megapolis in the American Bottom as the "Big Bang of Cahokia."

What triggered this tumultuous transformation?

Unfortunately, we can only speculate.

Perhaps a charismatic leader united the community, motivated by a desire to construct a flourishing metropolis. Maybe people could embark on large building projects because food was abundant.

According to Pauketat, the supernova SN 1054, recorded in sources worldwide in 1054, was interpreted by Cahokia's leadership as a divine cosmic sign, justifying the formation of a powerful central authority to oversee projects. The supernova is still visible with a telescope and, back in the day, could be seen during the day.

As a result of the Big Bang, Cahokia experienced a tremendous migration of people who were enamored with the New World Order. This is evident in the pottery found in Cahokia.

The early pottery reflects styles from the Coles Creek Culture (700-1250 AD) in current Louisiana and the Plum Bayou Culture (600-1000 AD) in northern Arkansas. Diverse burial traditions found at Cahokia also support the theory of migration. Further, analysis of dental remains of individuals buried in Cahokia revealed that 20-30% of people were migrants.

Why were so many people coming from all over America to Cahokia?

We've addressed how increased food security, trade, and transportation may have led to Cahokia's Big Bang. Other well-connected fertile regions in America existed, but there was only one Cahokia.

What attracted individuals to this metropolis?

Scholars believe that the transition in Cahokia was as much a cultural and political movement as it was an economic one. The Cahokian polity differed from previous Indigenous cultures. Pauketat describes it as a “political vortex” which sucked people in. The culture was highly stratified, with a chiefdom centered in Cahokia, the capital of a proto-state known by scholars as the Ramey state.

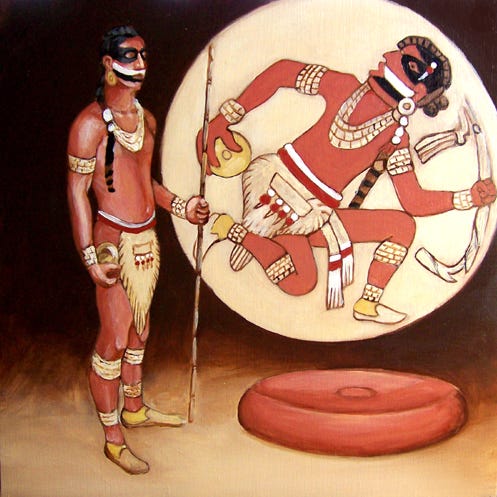

Gladiator games and the circus were vital to ancient Rome, and the Colosseum is undoubtedly its most well-known monument. Similarly, Cahokia was home to a high-stakes, popular sport called Chunkey.

Chunkey first appeared in the Mississippian Culture in approximately 600 AD. The sport involved sliding polished discs, or Chunkey stones, on a playing field. The player then tried to throw giant spears, several larger than him, as close to the Chunkey stone as possible. The game gathered large crowds, who cheered on their favorite players. It frequently entailed gambling, with some players risking everything they owned.

Much like the gladiator games of ancient Rome, the Cahokian elite used Chunkey to control the masses. Different game versions spread across the Great Plains and to the South. Pauketat suggests that emissaries from Cahokia visited tribes in the South and the Great Plains with Chunkey stones in one hand and war clubs in another. Combining the threat of violence and sporting diplomacy, these ambassadors enforced a region-wide peace “Pax Chaokiana.”

Though Chunkey was a crucial regional pacifier, the main appeal of Cahokia was its massive mounds. Jon has some intriguing details about these enigmatic structures from his visit to Cahokia Mounds State Historic Park.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Forgotten Footprints to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.