The Great Timbuktu Book Heist

How the city's librarians smuggled 400,000 ancient texts past Al-Qaeda

In June 2012, Al-Qaeda took over Timbuktu, a city on the edge of the Sahara desert. The goal of the terrorists was to wipe out the city’s history. They launched a vicious assault on Timbuktu’s UNESCO World Heritage sites.

One guy saw the Islamists coming for the thing every oppressor fears: knowledge. The man was Abdel Kader Haidara, the director of the Ahmed Baba Institute of Higher Learning and Islamic Research, an institute dedicated to preserving Mali’s past.

Since the 1990s, Haidara had painstakingly collected hundreds of thousands of priceless manuscripts, dating from the early 11th century through the 19th century. He was on a mission to prove that Africa has a tradition of writing history and preserving wisdom.

Haidara was racing against time, as the terrorists approached the city and planned to target his institute. He rounded up the rest of the librarians from Timbuktu and briefed them on the challenge ahead. There was a serious risk of losing the centuries-old texts.

They needed to hurry up.

Haidara and his colleagues risked their lives to rescue 95% of the volumes kept in Timbuktu’s libraries in the following nine months. They snuck past Al-Qaeda guards, delivering the manuscripts to safe hands in Mali’s capital, Bamako.

Because of their courage, journalist Joshua Hammer called them “Badass librarians of Timbuktu”.

What was special about Timbuktu's manuscripts? Why were librarians willing to risk their lives to protect them? More importantly, why did Al-Qaeda want to destroy the texts?

Let’s learn about a prosperous era in Mali’s past to find the answer.

Reminder: By choosing a paid membership (just $5 a month or $50 annually), you're helping amplify voices that history books too often overlook. Your support means these stories get the attention they deserve.

You’ll gain access to tons of members-only content👇

Full-length deep dives into untold stories: no paywalls, no cuts.

The entire archive of amazing stories from the Ice Age to the Fall of the Mongol Empire, the hottest archaeological finds, and the appetizing history of food.

Early access to special editions—be the first to dive in.

Join lively discussions in members-only posts and subscriber chats.

The Timbuktu manuscripts: Africa’s hidden history

I’m sure you’ve heard the expression “from here to Timbuktu.” In English, we use Timbuktu to mean a remote and difficult-to-reach place.

Once upon a time, Timbuktu was a thriving center of trade and knowledge. The site where the city was built was inhabited as early as the 5th century BC. However, until the 12th century AD, there was no permanent settlement. We credit the Tuareg people with the foundation of the modern city of Timbuktu. The Tuaregs are a nomadic pastoralist Berber ethnic group inhabiting the Sahara Desert, stretching from southern Libya to southern Algeria, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and as far west as northern Nigeria.

Timbuktu became a vital trading post because of its strategic location on the Niger River, on the southwestern edge of the Sahara Desert. The city flourished in the 14th century thanks to the salt, ivory, and gold trade.

Moroccan adventurer Ibn Battuta made the first written reference to Timbuktu in his works in 1353. In 1375, Timbuktu was featured in the Catalan Atlas, one of the most important medieval maps.

Emperor Mansa Musa, the ninth ruler of the Mali Empire, who reigned during the early 14th century, was primarily responsible for Timbuktu’s success.

In 1324, Mansa Musa conquered Timbuktu, and the city became part of the Mali Empire. Some sources suggest Musa may have been the wealthiest man ever, even after adjusting for inflation. The claim regarding Musa’s wealth is controversial, but the emperor’s support for knowledge and culture is undisputed.

Musa commissioned the construction of the Djinguereber Mosque and the Sankoré Madrasah at Timbuktu. The two institutions, along with the Sidi Yahya Mosque, whose construction began under the patronage of Sheik el-Mokhtar Hamalla in 1400, became known as the University of Timbuktu. During the Middle Ages, the university was one of the world's most important centers of higher learning.

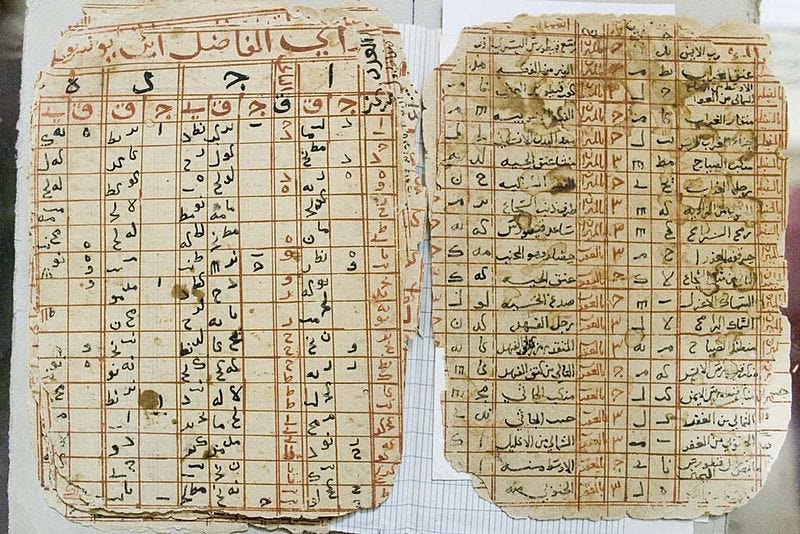

Scribes at Timbuktu University translated Plato, Hippocrates, and Avicenna’s writings. The books included works of art, medicine, religion, law, philosophy, and mathematics. They even touched on taboo topics such as human sexuality, which was almost unheard of in the Islamic world.

Among the works was The Mukham, a twenty-eight-volume Arabic dictionary created by an 11th-century Islamic scholar from Spain. An intriguing title in the collection is Advising Men on Sexual Engagement with Their Women, something you wouldn’t expect in a traditional medieval Islamic society. The book covers a range of topics such as aphrodisiacs, dealing with infertility issues, and advising men on winning the hearts of their wives.

The Timbuktu manuscript collection includes books on fortune telling, astronomy, magic spells, nutrition, herbalism, and law. In their heyday, the Timbuktu manuscripts may have numbered up to 700,000 volumes.

But there is something unique about this collection.

Unlike books in Europe and Asia, Timbuktu manuscripts were not cataloged and kept in public libraries. Instead, they were kept in people’s homes.

Ordinary citizens preserved the knowledge and passed down the books through the generations. As Timbuktu's glory days faded, people ensured the knowledge stayed safe. But migrations, wars, and famines dispersed the manuscripts around Timbuktu. There was no way to track the books, so recovering the scattered knowledge became difficult.

One curious young man was determined to collect the lost knowledge of Timbuktu’s past.

He was Abdel Kader Haidara.

The Fall of Timbuktu

Haidara was born to a family of scholars. He was well-versed in the works of Western thinkers. In the 19th century, European historians knew little about Africa’s past outside Egypt. There was a common perception that Africa had no written history. Because of the prevalent view among Western scholarship that Africa lacked written history, Haidara held the Timbuktu manuscripts in high regard. He wanted to show the world how generations of Africans risked their lives to keep written knowledge alive.

The real treasure of Timbuktu wasn’t gold, but books.

Haidara traveled all over Mali collecting ancient manuscripts and cataloging them for a library. He found the books in the homes of the rich and the poor, in villages and cities. Haidara haggled with individuals for the books. He persuaded the wealthy to donate their collections. His tireless efforts resulted in a compendium of 400,000 volumes from Timbuktu’s golden age. The books were housed at the Ahmad Baba Institute.

On June 13th, 2012, a splinter group of Al-Qaeda known as Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb attacked Timbuktu. The terrorist group took control of the Sub-Saharan city on June 29 after a brief fight.

The extremists began enforcing Sharia law. They stoned people to death and chopped off the limbs of alleged criminals in public. Aside from the population, the city’s rich heritage was targeted by Al-Qaeda. The terrorists desecrated the graves of many Sufi saints. They attacked the Djinguereber Mosque with hammers, axes, and chisels. Though the main building was spared, many of the shrines were demolished.

Al-Qaeda considered the Timbuktu manuscripts to be blasphemous. Unlike their interpretations, the writings dealt with a wide variety of issues. The terrorists regarded the texts as anti-Islamic, and as is characteristic of any tyrannical force, they would not accept any debate that contradicted their beliefs.

The terrorists set their sights on the collections at the Ahmed Baba Institute and other manuscripts that people had stored in their homes. Haidara’s lifelong work was about to go down the drain. Centuries of effort by Malians to preserve their ancient wisdom would be erased in the blink of an eye.

But the “badass librarians” were not about to give up their legacy without a fight. They were willing to risk their lives to save the books.

Mission impossible: Smuggling the books to safety

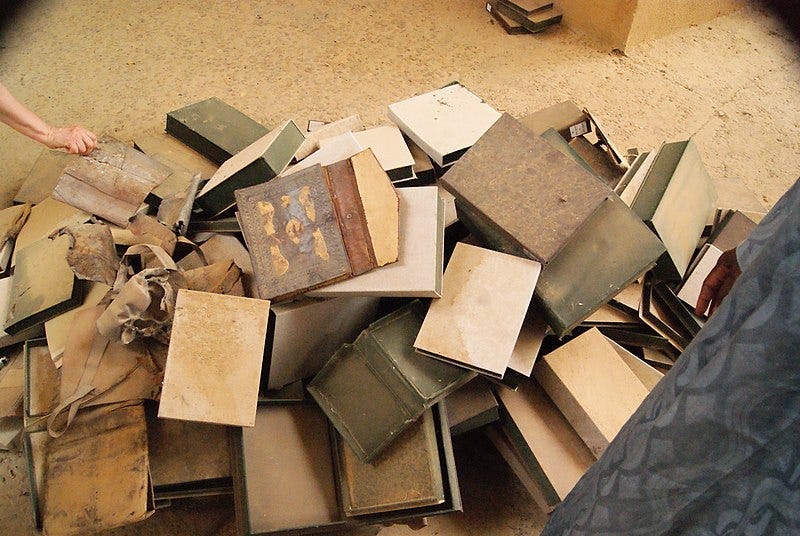

After the Al-Qaeda takeover, Haidara and other book-owning families met to discuss how to save the vulnerable texts. The librarians first concluded that they required volunteers to buy enormous footlockers suitable for storing the manuscripts.

Haidara and his friends put the books in the footlockers at night because terrorists were walking around town looking for suspicious behavior. Timbuktu was in a state of lawlessness, and there was rampant looting. People began informing terrorists about anyone they thought was dangerous, so the librarians had to exercise caution.

The first piece of the puzzle was carefully packing the books in metal crates without drawing the terrorists' attention. Getting them from Timbuktu to the capital, Bamako, was a far more challenging task.

It was very difficult. There were loads of manuscripts. We needed thousands of metal boxes and we didn’t have the means to get them out. We needed help from outside- Abdel Kader Haidara.

The librarians needed a significant amount of cash to send the boxes safely. Al-Qaeda operatives had set up several checkpoints, so one had to be discreet. A wrong move would jeopardize the entire operation. The distance from Timbuktu to Bamako is 606 miles, and books had to be slipped through dangerous areas.

The German Foreign Office and the Prince Claus Foundation of the Netherlands funded the operation.

Haidara and the other librarians sent the boxes on trucks, canoes, and carts. Often, the trunks were hidden under vegetables and fruits. At times, the footlockers were camouflaged as the personal possessions of fleeing refugees.

Duping Al-Qaeda wasn’t a guarantee for the safe passage of the boxes. The Malian government was collaborating with the French troops to prevent Al-Qaeda from taking over the entire nation. A French helicopter saw the boxes going up the Niger River and stopped them right away. The French threatened to open fire because they suspected the canoe of smuggling weapons.

Thankfully, the transporters showed the contents of the boxes to the French soldiers, who let them go.

There were some close calls. Haidara’s nephew, Mohammed Touré, the library curator, was caught by the Islamic police and charged with stealing books. Touré, fortunately, escaped after a 24-hour incarceration in prison owing to his understanding of Islamic law and his uncle’s connections.

The mission of the guardians of knowledge to smuggle the Timbuktu manuscripts to Bamako was a success. In nine months, 95% of Timbuktu’s books were securely transported to a library in the capital.

By the time the Islamists found the library in Timbuktu, almost all the shelves were empty. Angry at being outwitted by a group of librarians, the terrorists burned 4,000 manuscripts from the initial collection of 400,000.

The Islamists wanted to destroy everything, but thanks to the courage of Haidara and his colleagues, future generations can benefit from the timeless knowledge of the Timbuktu manuscripts.

What happened to the manuscripts after they reached Bamako?

After saving them from the terrorists, Haidara and his friends are now racing against time to prevent the manuscripts from degrading. SAVAMA-DCI, an NGO, is working with the librarians to digitize the books.

You can view many of the digitized manuscripts in Google Arts and Culture. Bibliophiles worldwide hope that Africa’s incredible written history will be preserved.

Haidara wanted to show the world there is much to learn about Africa beyond colonialism and slavery. Thanks to his efforts and the digitization of the Timbuktu manuscripts, we can appreciate a forgotten chapter from Africa’s history.

Do you love exploring the mysteries of lost civilizations and the rich cultures of the ancient world?

Share this story with friends and family, and don’t forget to subscribe to this newsletter for more fascinating insights!

If you enjoyed this story and would love to read more such stories, please upgrade to a paid membership.

References

Park, Douglas (2010), Timbuktu and its prehistoric hinterland.

Hammer, Joshua (2016), The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu.

The Timbuktu Job by National Geographic.

This is fascinating! Glad people like Abdel exist. It reminded me of seeing BBC documentaries by Zeinab Badawi about the rich history of Africa. The Mali and surrounding countries definitely being an ancient forgotten civilisation.

Thank you for sharing this story!

That’s awesome, I never knew about this act of heroism! It’s nice to hear about people safeguarding our collective past from ideologues who would destroy the parts they don’t like. Reads like an adventure story too