The Forgotten Storyteller behind Aladdin

Aladdin wasn’t a part of the original Arabian Nights; meet the man who narrated the tale

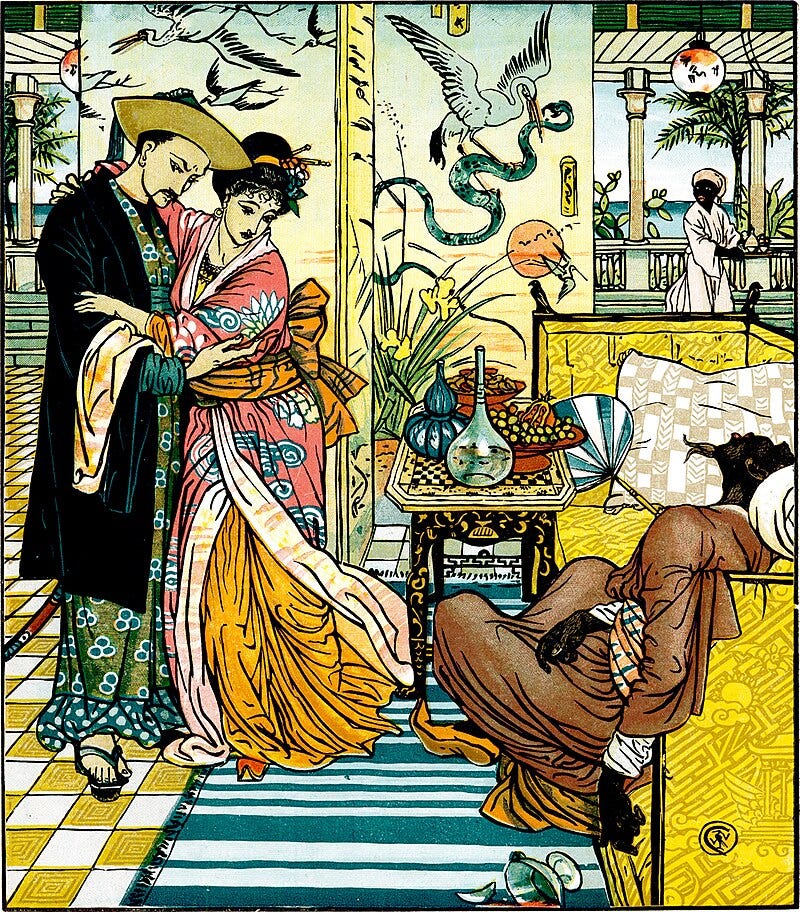

Aladdin and the Magic Lamp is one of the best-known tales from the Arabian Nights. The story has everything needed for a perfect fairy tale: a young orphan who falls in love with the Sultan’s daughter, a wish-granting genie in a magical lamp, and an evil wizard plotting the protagonist’s downfall.

Disney’s iconic 1992 rendition made Aladdin a household name. I loved the film as a kid, and it inspired me to look up the original story. When I first read Aladdin, I was surprised to learn he was from China, not the Middle East.

The original version and Disney’s adaptation differ in many ways.

Years later, I discovered Aladdin and another well-known tale, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, weren’t a part of the original Arabian Nights. They’re my favorite stories from the book, and I wanted to know how they ended up in the literary work.

My search led me to Antoine Galland, an eighteenth-century French orientalist who incorporated the tales of Ali Baba and Aladdin into the Arabian Nights.

But he didn’t write them.

Aladdin’s story was narrated by Hannah Diyab, a Syrian adventurer who met Galland in Paris. Diyab was a storyteller who visualized a fantasy world based on his life. Scholars believe he was the inspiration behind Aladdin.

We didn’t learn about Diyab’s contribution to the Arabian Nights until 2015. Translated into French, his autobiography revealed the truth about Aladdin and several other stories.

Why didn’t we know about this earlier? As we shall see, Galland did everything he could to erase Diyab’s legacy and almost succeeded.

Before we learn about the man behind Aladdin, let’s find out how the Arabian Nights reached Europe.

Europe Reads the Arabian Nights

Alf Laylah wa-Laylah, popularly known as the Arabian Nights or Thousand and One Nights, is set in Persia during the Sassanid Empire (224–651 AD). Shahryar, the king and the story’s main protagonist, is horrified to learn that his wife cheated on him. He executes her. He then marries virgin women and puts them to death the next day after the wedding.

The king’s vizier handpicked these unfortunate women. Rumors spread when the ladies disappeared after marrying the king. Eventually, the vizier ran out of potential suitors.

In a move that shocked her father, Scheherazade, the vizier’s daughter, offered to marry the king. She keeps Shahryar interested in her by telling him an incomplete story, and the king becomes curious about what will happen next. A new night and an unfinished tale continued for a thousand and one nights, during which she had two children with the king. Her stories move Shahryar, who agrees to make her queen instead of killing innocent women.

The Arabian Nights are a series of stories told by Scheherazade to Shahryar. However, the original book didn’t have Aladdin and Ali Baba.

So, how did they become part of the book?

Antoine Galland worked as an orientalist for the French Embassy in Istanbul in the late 17th century. Galland spoke Greek and learned Persian, Arabic, and Turkish during his travels in the Middle East and India.

He was fascinated by Middle Eastern literature and came across the Arabian Nights. He translated the work into French as Les mille et une nuits. The first volume appeared in 1704, and the twelfth and last volume was published in 1712.

The most iconic literature of the Middle East had arrived in Europe.

The books were an instant hit.

We won’t discuss the original Aladdin story in detail, as our focus is on the man behind the tale. But it's essential to know the key differences between the Disney version and the book.

In the original story, Aladdin is not an orphan but a lazy young man who lives with his mother. The plot is set in China rather than the Middle East. There are two genies instead of one. The princess’s name is Badr al-Badour, not Jasmine. The book version has dark elements, such as Aladdin kidnapping the princess with the help of his genie and murdering the sorcerer and his brother.

You might be wondering: if the original tale is set in China rather than Agrabah (the fictional city based on Baghdad in Disney’s Aladdin), why does its theme feel distinctly Islamic?

When the story was composed, the idea of China was not the country we know today, but that of a far-off, distant land. At the edges of Imperial China was the Turpan Khanate, in present-day Xinjiang. It was an Islamic monarchy founded in 1487 by the descendants of the erstwhile Chagatai Khanate.

The Turpan Khanate lasted till 1570 when it was conquered by the Yarkent Khanate, which was also an Islamic kingdom. Hence, the idea of an “Islamic Chinese sultanate” may have been based on these Khanates, which flourished near the borders of China and Central Asia between the 15th and 17th centuries.

Both the modern and the original versions of Aladdin have a common theme: a rags-to-riches story with a happy ending. Historians suspect that Galland invented Aladdin and Ali Baba and added them to the book. No Arabic manuscripts of the tales existed before he published the stories. The French orientalist heard about Aladdin’s tale from a Syrian man he met in Paris.

Galland mentions him in his diaries as “Hanna from Aleppo.”

Hanna Diyab: The Real Aladdin

Antun Yusuf Hanna Diyab (aka Hanna Diyab) was born in Aleppo, Syria, in 1688. He was a Maronite Christian who spoke Turkish, French, and Italian and could read Aramaic and Syriac. He was into alchemy and claimed to have raided an ancient tomb.

Unfortunately, he lost his father when he was young. In 1707, he met Paul Lucas, a French naturalist and antique dealer with ties to French nobility. The talented Syrian impressed Lucas, who welcomed him to France. Diyab, an adventurous guy, accepted Lucas’s offer without hesitation.

Lucas and Diyab set out from Aleppo on an incredible journey to Tripoli, Sidon, Beirut, Cyprus, Egypt, Corsica, Livorno, Genoa, and Marseille before arriving in Paris in 1708. At Versailles, they were given a royal reception.

Diyab’s ability to speak multiple languages and charming demeanor impressed the French aristocracy. Lucas recommended him for a position at the Royal Library in Paris.

In March 1709, Diyab met Galland in Paris. With his first volumes of the Arabian Nights, Galland had made a name for himself in Europe and was appointed the Arabic chair at the Collège de France. However, he needed additional content for the Arabian Nights and wanted to print more volumes.

Galland, impressed with Diyab, invited him to tell some stories. The Syrian gladly obliged and started narrating tales based on his childhood memories, including Aladdin, Ali Baba, and others. Galland recorded the accounts in his diary.

This is where we see a cruel twist of fate.

Though Diyab told Galland the story of Aladdin, the latter didn’t give him credit. Hanna Diyab is not mentioned once in Les Mille et Une Nuits. Paul Lucas also said nothing about the Syrian storyteller in his writings. Historians have discovered Diyab thanks to Galland’s diaries.

Things got worse for Diyab in Paris. Remember the position Lucas recommended him for in the Royal Library? Galland also wanted the job, but he felt threatened by Diyab. The gifted young man, fluent in several languages and well-liked in the French court, challenged his ambitions.

Galland took advantage of his political contacts to deport Diyab to Aleppo in 1710. Thus, he eliminated his competition for the coveted job at the Royal Library and reduced the Syrian to a footnote in his diary.

Initially, there were doubts about Diyab’s existence. Historiographers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries believed that Galland invented the Arabian Nights to give them a more “exotic” flavor. Scholars thought that Galland was the original creator of Aladdin.

Lucky for us, Diyab ensured his story wouldn’t fade into oblivion.

After returning home, he and his brother Abdallah started a clothing company. Their business boomed. Diyab became wealthy, married, and had a happy family. In 1763, aged 75, he penned his autobiography, describing his life’s journey, triumphs, and betrayals.

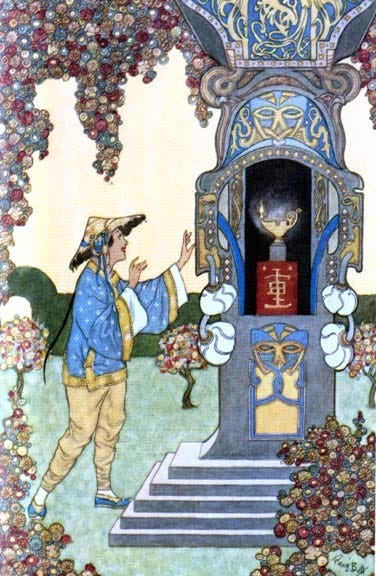

His autobiography revealed striking similarities with Aladdin’s story. Diyab, an ambitious orphan with a thirst for adventure, used Aladdin to create an imaginative version of his life. A poor boy who falls in love with the Sultan’s daughter, powerful genies who grant him his wishes, and an evil sorcerer who wants to destroy him- Diyab wanted Aladdin’s world.

Some scholars believe the magnificent Palace of Versailles and the luxurious life of Paris fueled Diyab’s imagination. His tomb raiding is echoed in Aladdin’s cave diving to get the magical lamp for the sorcerer. The story’s genies and magical themes reflected Diyab’s enthusiasm for alchemy.

His autobiography also reveals how Galland conspired against him and had him deported after using his stories: a sad tale of betrayal.

But, like Aladdin, Diyab’s story has a happy ending.

In 1993, the Vatican Library unearthed an Arabic manuscript titled Sbath 254. The document was Hanna Diyab’s autobiography. It was translated into French in 2015, giving the literary world a fresh take on the Arabian Nights.

Despite the denial of credit, contemporary scholars have determined that Hanna Diyab told multiple Arabian Nights stories published by Galland from March 25th to June 2nd, 1709, including Aladdin. The Syrian adventurer was the rightful author.

Regrettably, Diyab died an unappreciated man. Yet, like Aladdin, he had a happy ending as his memoir ensured the literary world recognized his contribution. His legacy as the author of some of our most treasured fairy tales will endure forever.

References

John Payne, Alaeddin and the Enchanted Lamp and Other Stories, (London 1901)

Irwin, Robert (2003), The Arabian Nights: A Companion

Bottigheimer, Ruth B (2014). East Meets West: Hannā Diyāb and The Thousand and One Nights’, Marvels & Tales.

Horta, Paulo Lemos (2019). Marvellous Thieves: Secret Authors of the Arabian Nights. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wow, I did not know this. Thank you for writing this.

Behind the magic of Aladdin lies a story almost as extraordinary as the tale itself. The genie, the lamp, and the daring hero weren’t born in the pages of ancient manuscripts, but in the mind of Hanna Diyab—a Syrian adventurer whose name Antoine Galland tried to erase. For centuries, the world believed Aladdin came from the Arabian Nights; only in 2015 did we uncover the truth.