Did Steppe Empires Leave Behind Written Records?

Tracing the origins of scripts in the Eurasian Steppes

History remembers the Steppe nomads as masters of the bow and the saddle but not the pen. What if I told you that this narrative is a myth? From the giant steeles in the Orkhon Valley to the ambitious universalism of Kublai Khan’s Phags-Pa script, the nomadic empires of the Eurasian Steppe didn’t just ride across history—they wrote it.

I noticed something unusual when I first started reading about Eurasian Steppe Empires. The primary historical sources about these powers were almost always from their rival civilizations.

We rarely hear the narrative from the point of view of the Steppe people, which made me wonder if they knew writing and practiced record-keeping. What were their scripts like?

After the Russian Empire captured most of Central Asia in the nineteenth century, Cyrillic, used to write Russian, became the default script in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. The same happened in Mongolia after the Soviet-backed Communist Revolution of 1921. The upheavals resulted in several records of the past being lost.

However, the Russian expansion across the Eurasian Steppes also sparked a curiosity about the region’s ancient empires.

In this newsletter, we’ll discuss the origins of writing in the Steppes and learn how nomads went from adopting scripts to devising a universal writing system. I’ll be covering the scripts of the Xiongnu, the Göktürk, the Uyghurs, and the Mongols. We’ll begin our search for the first Steppe script with a disgruntled courtier from the Han Dynasty in the 2nd century BC.

Before we dive in, here's a quick thank-you: As a subscriber, you can now enjoy a lifetime 15% discount on the annual membership plan—just my way of showing appreciation for your support!

The Hu Script: Origins of Writing in the Steppes

Before we discuss the Hu script, let’s review the political situation of Inner Asia in the second century BC.

The Xiongnu Empire (3rd century BC–1st century AD) was the first empire to rise from the Steppes. It was the ancient world’s largest empire, surpassing Alexander’s Macedonian and the Persian Achaemenid empires.

The Xiongnu, based in the Orkhon Valley of Mongolia, was a confederacy of nomadic peoples living north of China. Linguists believe the Xiongnu elite spoke Turkic and Yinesian languages, but they also had proto-Mongolian and Indo-European speakers in their coalition.

Most of our knowledge of the Xiongnu comes from the monumental work of the Han historian Sima Qian. The Xiongnu were bitter rivals of the Han dynasty, which ruled China. Hence, his accounts of the nomads were far from flattering.

In 200 BC, the Xiongnu, led by Modu Chanyu, destroyed the Han army at the Battle of Baideng. After the defeat, the Chinese offered the Xiongnu silk, wine, money, and princesses to maintain peace. This policy was known as heqin.

During one such entourage to the Xiongnu in 170 BC, the Chinese sent Zhonghang Yue, a eunuch from the Han court. Yue was furious at being “gifted” to the Xiongnu and vowed to be China’s worst enemy.

He taught the Xiongnu several state secrets, including writing and bureaucracy. According to Chinese records, when the Xiongnu received correspondence from the Han, the spiteful Yue advised Jiyu Chanyu (Modu’s son, also known as Laoshang in Chinese records) to use a “bigger wooden board and seal to reply to the Chinese emperor.”

The act was to show the Xiongnu’s superiority.

Like other ancient legends, we must exercise caution in taking Yue’s vengeful counsel at face value. But, the story reveals that the Xiongnu knew how to write. According to Sima Qian, when the Xiongnu took notes, they made slashes on a piece of wood.

The Chinese called this writing style the “Hu” script. “Hu” is a generic term for “barbarians” or nomadic people who lived in the North of China, and Chinese historians perceive them as lacking civilization.

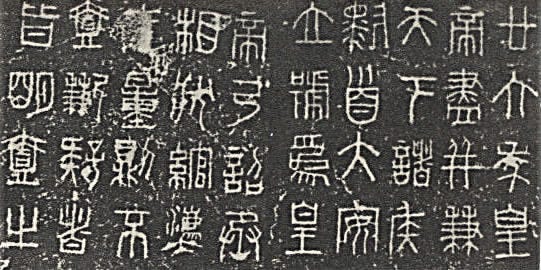

Historian Kenneth Harl offers an alternative theory about the origin of the Hu script. He claims that Modu’s officials created the writing system based on the small seal script enforced across China by its first emperor, Qin Shi Huang.

According to Harl:

Modu Chanyu and his successors could easily find numerous Chinese scribes to keep records on wooden tablets and to write up their demands as directives and laws. Modu Chanyu’s officials devised their own script based on the Chinese ideograms imposed by the emperor Qin Shi Huang. Modu Chanyu’s successors expanded and reformed this bureaucracy, and so they created an imperial institution with its own collective memory. It might well have persisted long after the fall of the Xiongnu Empire, and inspired the later Gök Turk and Mongol kaghans who appreciated the power of writing.

Modu and the Xiongnu set a precedent for the future Steppe empires to keep written records. This challenges the popular perception of a lack of a literary tradition in the Steppes during ancient times. Writing was always valued, and the Xiongnu welcomed ideas of a sophisticated administrative system that involved communication.

We’ve established that the Xiongnu knew how to write, but do we have proof of the Hu script?

Archaeologists discovered over twenty carved characters of the writing system at a burial site in Noin-Ula near Lake Baikal in Mongolia. These characters are similar to the Old Turkic alphabet, which some linguists believe had roots in the Hu script.

Unfortunately, we have limited information about Hu. The evidence unearthed at Noin-Ula is insufficient to know precisely what the script was and to what extent it was prevalent. From Chinese history, we are fairly confident that the Xiongnu knew how to write, but a lack of surviving records makes it difficult to learn more about the writing system.

Luckily, we don’t need to leave Mongolia to find the oldest undisputed proof of a script developed by the Steppe people.

Old Turkic: The Oldest Preserved Script of the Steppes

In 1889, Nikolai Mikhailovich Yadrintsev, a Russian archaeologist, discovered Chinggis Khan’s capital, Karakorum, in Mongolia.

But one of his other finds is vital for our story.

In Mongolia’s Orkhon Valley, Yadrintsev unearthed two gigantic monoliths containing the earliest undisputed proof of a written language in the Steppes. In 1893, Vasily Vasilievich Radlov, a schoolteacher from Siberia interested in Turkic languages, heard about Nikolai Yadrintsev’s discovery of the Orkhon inscriptions. Radlov published the Orkhon Inscriptions and is remembered as one of the leading figures who started the discipline of Turkology, the scientific study of Turkic languages.

Radlov’s publication caught the eye of Danish linguist Vilhelm Thomsen. In the same year, Thomsen deciphered the Orkhon inscriptions, forever changing our knowledge about writing in nomadic societies. Before Thomsen decoded the Old Turkic script, it was widely believed the Turks and predecessor nomadic powers lacked a written script or depended on other literate people, such as the Chinese and Sogdians, for official communications.

The Orkhon Valley lies 320 kilometers west of Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar. The area was the seat of power of the Göktürks and the Xiongnu. I have covered Göktürks in detail in an earlier story. Please check it out if you’d like to know more about them.

In 732, Göktürk rulers Bilge Khagan and his brother Kul Tigin constructed two colossal monoliths in the region. Bilge Khagan was the fourth ruler of the Second Turkic Khaganate, which arose after the collapse and subjugation of the First Turkic Khaganate by the Tang dynasty of China.

The Turks had a complex relationship with the Chinese Tang dynasty, and the Turkic scribes lamented their loss of freedom in the inscriptions. The Steele asks Turks to shun Chinese luxuries, live in walled cities, and live in felt tents known as gers(Mongolia) or yurt (Russian) on the open Steppes. The dire situation of the Turks is summed up in the inscriptions:

The sons of the nobles became the bondsmen of the Chinese people, their unsullied daughters became its slaves. The Turkic begs gave up their Turkic names, and bearing the Chinese names of Chinese begs they obeyed the Chinese Emperor, and served him during fifty years. For him they waged war in the East towards the sun's rising, as far as Bokli kagan, in the West they made expeditions as far as Taimirkapig; for the Chinese Emperor they conquered kingdoms and power. The whole of the common Turkic people said thus: 'I have been a nation that had its own kingdom; where is now my kingdom? For whom do I win the kingdoms? said they. I have been a people that had its own kagan; where is my kagan? Which kagan is it I serve?'

Though the Orkhon inscriptions are the earliest surviving form of Old Turkic, there’s proof that the script may be older. According to the seventh-century Book of Zhou, which documents the histories of China’s Western Wei and Northern Zhou dynasties, the Turks used a writing system comparable to the Sogdians.

Besides Sogdian, the Brahmi-derived Tocharian script also influenced Old Turkic. Brahmi was the primary script of ancient India, popularized in Central Asia by Buddhist monks. Before the full-fledged use of Old Turkic, Brahmi may have been the Turks' default script.

The Bugut inscription in Mongolia, written during the reign of Taghpar in 582, was in Sogdian and Brahmi. The language of the Brahmi script was once thought to be Sanskrit, but in 2014, linguists concluded it was an early version of Mongolian. Surprisingly, there was no Turkic language in the Bugut inscription. This isn't the only Mongolic Brahmi inscription found.

The Hüis Tolgoi inscription, dated to the early seventh century and possibly commissioned by Niri Khagan, was also in Mongolic Brahmi, demonstrating that the Turks used a written script before establishing their own.

Another theory suggests that Old Turkic had its roots in the Xiongnu’s Hu script. These characters resemble the Old Turkic alphabet, but the links are tenuous at best.

The evidence for the widespread use of the Hu script across the Steppes is limited. We don’t know if it significantly impacted the development of Old Turkic. In contrast, archaeologists have unearthed over 200 inscriptions written in Old Turkic across Eurasia.

The writing system introduced by the Göktürks laid the foundation for Steppe peoples such as Uyghurs, Khitans, Mongols, and Manchus to develop their scripts. The successor states put a greater emphasis on written records for communication, which became integral to empire-building.

Old Uyghur: A Foundational Script

Just a decade after the Orkhon Inscriptions were composed, the Second Turkic Khaganate and the rule of the Göktürks ended.

In 744, a civil war broke out between the Göktürk and one of their vassals, the Uyghurs Qutlugh Bilge Kol. Qutlugh led an alliance of disgruntled rebels and attacked Otuken, defeating and beheading the last Göktürk Khagan, Ozmish.

With the collapse of the Göktürks, a new Turkic Khaganate, the Uyghur Khaganate, emerged.

Following the conquest of Otuken, the Uyghurs constructed Ordu-Baliq, their new city, atop the foundations of the former Göktürk metropolis.

The Uyghurs built upon the legacy of the Göktürks, making Ordu-Baliq a flourishing city of international commerce. Writing was vital for the Uyghurs, who continued using the Old Turkic script their predecessors invented.

However, within a century of ascending to power in the Orkhon Valley, the Kyrgyz defeated the Uyghurs, and their capital was sacked. A group of Uyghurs settled in Xinjiang and adopted the Sogdian Brahmi alphabet to devise the Old Uyghur script.

Centuries later, the Uyghur script became a prototype for the Mongol and Manchu scripts.

Phags-Pa: The Universal Script

Before Chinggis Khan’s rise in 1206, the Mongols didn’t have a writing system. After conquering the Uyghurs, the Great Khan instructed his new subjects to devise a script for the Mongols. Tata-tonga, a Uyghur scribe, introduced writing to the Mongols and adapted the Old Uyghur alphabet to form the Mongolian script.

The Uyghur script, written vertically like Chinese, is alphabetic and accurately represents the sounds of most Steppe languages. Thus, Mongolian can be conveniently expressed in Uyghur.

In 1260, Chinggis’ grandson Kublai became the Great Khan. His army had many Chinese soldiers, and several Chinese officials joined his service.

This created a communication problem.

Kublai knew he couldn’t use the Mongolian script to write Chinese because China had a 3,000-year-old writing tradition. Using the Chinese script to write Mongolian was also tricky, and Kublai’s officials had to rely on translations.

The Khan was facing a bureaucratic nightmare. How do you manage personnel who speak and write many languages without getting taken for a ride?

In 1267, Kublai met Phags-pa, a Buddhist Tibetan monk, and conveyed his vision. He asked the monk to create a new script to write any language used in the Mongol Empire.

Phags-pa was proficient in Sanskrit, Tibetan, Chinese, Mongolian, and Uyghur. After two years, he devised a script with sixty signs, most of which were consonants, vowels, and a few syllables. This new writing system was named after the monk, and we call it the Phags-pa script. The script is read vertically, like Uyghur. The letters comprise straight lines and right angles. Hence, Mongolians call it the “square script.”

Kublai Khan established schools to teach the Phags-pa script. However, the Mongols soon discovered that altering bureaucracy was more difficult than demolishing walled cities.

Despite Kublai Khan’s efforts to establish an academy for studying and promoting the Phags-pa script, his officials obstructed its implementation. As is often the case with bureaucrats facing inconvenient orders, they feigned compliance but took no real action.

The resistance was not because of the script’s shortcomings but rather the inherent nature of humans. Mastering a new script, regardless of its simplicity, is daunting. Traditional writing systems are challenging to replace.

Convincing Chinese officials to abandon their millennia-old writing system was as futile as trying to move a mountain with your bare hands.

This story taught us that record keeping existed in the Steppes as far back as the second century BC. Since the days of the Xiongnu empire, the ruling elite of the Steppes appreciated writing and understood how crucial it was for their empires.

The Göktürks initially adopted scripts of Sogdians and Tocharians but soon created the Old Turkic alphabet, which paved the way for later Steppe scripts.

Before Chinggis Khan’s rise, the Steppes had several writing systems. The Mongols adopted the Uyghur script. The Mongolian script sufficed to express Steppe languages, but communication became difficult when Chinese officials joined the Mongol Empire.

Kublai Khan envisioned a universal script that could write any language, and Phags-pa, a Tibetan monk, devised it. The Phags-pa script failed to catch on because of bureaucratic inertia, but it signified that the people of the Steppes had come a long way from adopting scripts to creating a universal writing system.

Do you enjoy tales from lost civilizations and cultures from the ancient world and the Middle Ages?

Share this story with your friends and family and subscribe to this newsletter.

References

Ross, E. Denison; Vilhelm Thomsen (1930). “The Orkhon Inscriptions: Being a Translation of Professor Vilhelm Thomsen’s Final Danish Rendering.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London.

Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic peoples.

Watson, Burton (1993), Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian, Columbia University Press

History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol II, UNESCO Publishing.

History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol III, UNESCO Publishing.

John Man (2014) Mongol Empire: Genghis Khan, his heirs and the founding of modern China.

Harl, Kenneth W. ( 2023). Empires of the Steppes: A History of the Nomadic Tribes Who Shaped Civilization.

My special interest is central asian history because it’s rich and not easily accessible to English speakers. Thank you for the enlightening article!

Absolutely fascinating! Thank you for this.