Curry's Journey to the Land of the Rising Sun

How historical events shaped Japan's national dish

The first time I tried Japanese curry, I was amazed by its unique flavor. It wasn’t like any curry from the Indian subcontinent or Southeast Asia. The dish had a silky smooth finish with a tinge of sweetness, reminiscent of a European stew with potatoes and carrots complementing the meat. However, the flavors were predominantly Asian. I could taste the soy sauce with a prominent mix of cumin, coriander, black pepper, and turmeric.

I had katsu curry. It’s a deep-fried pork cutlet served over rice with a brown sauce, and I’ve had it or seen it on the menus in Japanese restaurants in the US, Canada, India, and Thailand.

Though many people associate Japanese food with sushi, ramen, and tempura, Japanese curry is growing popular worldwide. More Japanese restaurants outside Japan now serve curry.

Curry is an emerging category of Japanese cuisine globally, but has a different appeal in Japan. It arrived in Japan in the late 1800s, and the country has been obsessed with it ever since. In a 2008 survey, 10,000 people labeled curry as Japan’s national dish, and most reported eating it many times a month.

Curry has a unique history in Japan. British rather than Indian or Southeast Asian traders brought it to the land of the rising Sun. Japanese curry resembles a European stew. A roux thickens the sauce, unlike Indian or Southeast Asian curries, which simmer spices with vegetables, meat, tomatoes, coconut milk, or yogurt, enabling the gravy to thicken naturally.

The Japanese palate desired curries, and by the early twentieth century, Indian curries had been introduced, rivaling the popularity of British-style curries.

I was intrigued by Japan’s love for curry.

How did curry become Japan’s national dish?

To understand Japan’s fascination with curry, we must discuss the origins of one of the dish’s key ingredients: curry powder. The spice blend was a European creation born out of the lack of understanding of the finer nuances of Indian cuisine.

Reminder: By choosing a paid membership (just $5 a month or $50 annually), you're helping amplify voices that history books too often overlook. Your support means these stories get the attention they deserve.

You’ll gain access to tons of members-only content👇

Full-length deep dives into untold stories: no paywalls, no cuts.

The entire archive of amazing stories from the Ice Age to the Fall of the Mongol Empire, the hottest archaeological finds, and the appetizing history of food.

Early access to special editions—be the first to dive in.

Join lively discussions in members-only posts and subscriber chats.

The Colonial Origins of Curry Powder

Among Indian cooks, the word curry elicits mixed emotions. Europeans lump together under the term curry many Indian foods that aren’t “curry.” So if you ask Indian chefs to make a “dal curry” or a “butter chicken curry,” they might frown upon you. Some Indian food critics claim that Indian cuisine has no dish called “curry.” But that isn’t true and is a reaction to the lazy branding of diverse Indian dishes under one banner.

Curry is derived from the Tamil word “kari,” which refers to the curry tree (Bergera koenigii) leaves and some gravies produced with them. Other South Indian languages also contain the word “kari.”

A 17th-century Portuguese cookbook describes the first documented recipe for kari in Europe. The British followed the Portuguese in their attempt to dominate the lucrative spice trade, and they quickly fell in love with kari. The Portuguese used caril for kari, whose plural was carie or curee, which eventually became the anglicized “curry.”

Boundaries blurred because neither the Portuguese nor the British cared about the subtleties of Indian food. Europeans labeled any spicy dish from the Indian subcontinent with a sauce as curry, which might explain why the word annoys Indian food critics.

Indian chefs add spices based on the dish being prepared. However, European traders ignored this tradition and began combining coriander, cumin, fenugreek, black pepper, and ginger and marketed it as “curry powder.” Crosse and Blackwell (C&B), an English company, introduced the first instant curry powder in 1784.

The spice mix was promoted as the perfect solution for all Indian-style dishes. All you had to do was add meat, vegetables, water, and salt, and the curry was ready.

The product quickly became popular among British colonies worldwide and was a luxury item. The British Navy found curry powder helpful since the spices improved the preservation of their stews, and thanks to their sailors, Japan got its first taste of curry.

Curry Arrives in Japan

According to popular belief, curry was introduced to Japan in the late 1800s by a British sailor who was shipwrecked and rescued by a Japanese fishing boat. Because curry powder was a staple in the Royal Navy, he brought a few tins and taught the Japanese how to use it in a stew.

A more realistic explanation of the curry’s origins is connected with the changes to Japanese eating habits during the Meiji period (1868–1912). Emperor Meiji took over Japan’s administration on January 3, 1868, marking the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the beginning of imperial authority. Historians refer to the event as the Meiji Restoration.

The Meiji era saw a significant shift in people’s diets from the preceding Edo period (1603–1868). Historically, meat consumption in Japan was minimal, and animal slaughter was prohibited.

In 1872, the authorities reported that the emperor ate beef, signaling a shift in public opinion toward meat. The Meiji government’s motto was “enrich the country, strengthen the army,” as they attributed the muscular physiques of the Europeans to their meat intake.

But how can one provide sufficient meat for a growing army?

Enter curry.

Although curry was served in Japanese restaurants by 1877, it first gained popularity in army mess halls. Easy to cook in large batches, curry became the preferred choice for adding meat to the soldiers’ diet.

The Japanese Navy also embraced curry. Before the Meiji Restoration, Japanese sailors were given miso soup, rice, and pickles. Because of the lack of meat, beriberi was prevalent in the navy.

The British Navy served curry with bread, and Japanese chefs followed suit, but instead of bread, they thickened the sauce and served it over rice.

The early versions of Japanese curry differed from the katsu curry I had. Curry recipes were first published in two books in Japan in 1872. Kaigaku Shujin’s Proposed Western Style Menus (seiyō ryōri shinan) had a recipe for making curry with brown frogs, spring onions, and curry powder. Kanagaki Robun’s Connoisseur of Western-Style Cuisine (seiyō ryōri-tsu) features another beef or mutton curry recipe.

But in both recipes, something was missing.

Where were the potatoes and carrots?

A Civil War Veteran Brings the Potato

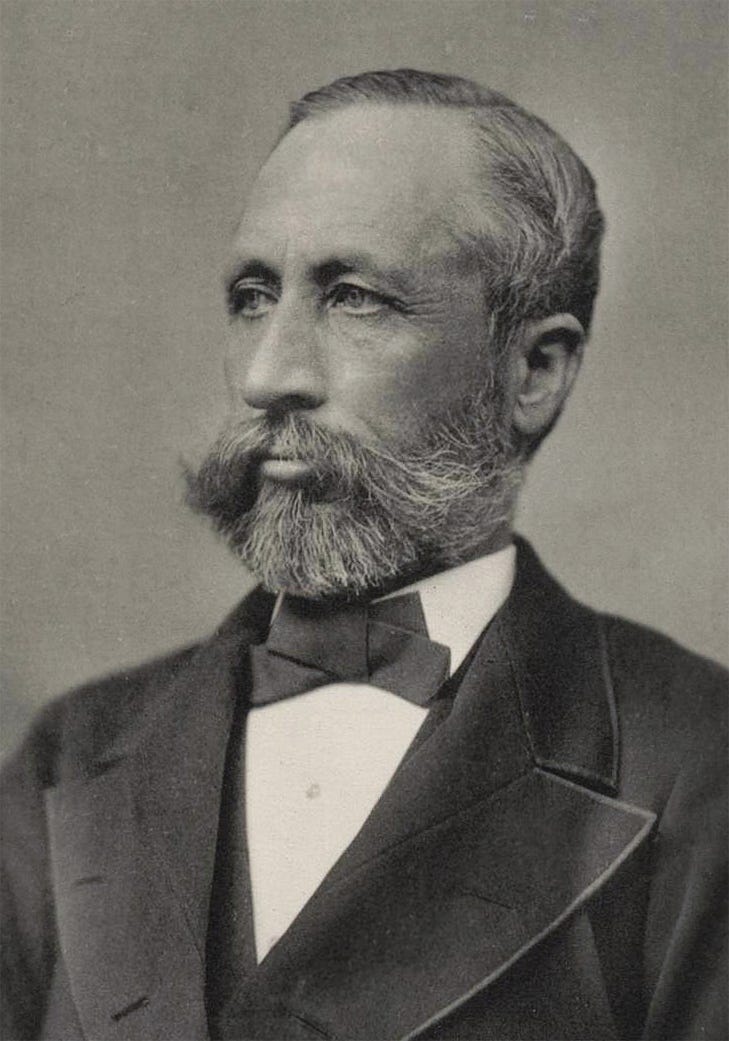

William S. Clark, an American chemist and agriculturist, is credited with introducing potatoes and carrots into Japanese curry. Clark, a Civil War veteran, had lobbied to establish the Massachusetts Agricultural College and later served as its President once it was moved to Amherst.

However, Clark was upset by politics over grant and land allocation, curriculum disputes, and media criticism. A total lack of support from Massachusetts’ farming community, who distrusted Clark’s revolutionary ideas, worsened the situation.

But 7000 miles away, Clark found appreciation for his work. In 1876, the Japanese government hired Clark to set up the Sapporo Agricultural College (now Hokkaido University).

Japanese students embraced his ideas.

One of Calrk’s revolutionary innovations was farming potatoes on a mass scale to counter rice shortages. He advised adding potatoes and carrots to the curry to make it more appealing, and the suggestion was a hit.

Japan’s appetite for curry increased, and people wanted to try different flavors. As the British-style curry gained popularity in Japan, it soon faced competition from Indian curries.

Indian Freedom Struggle and the Curry

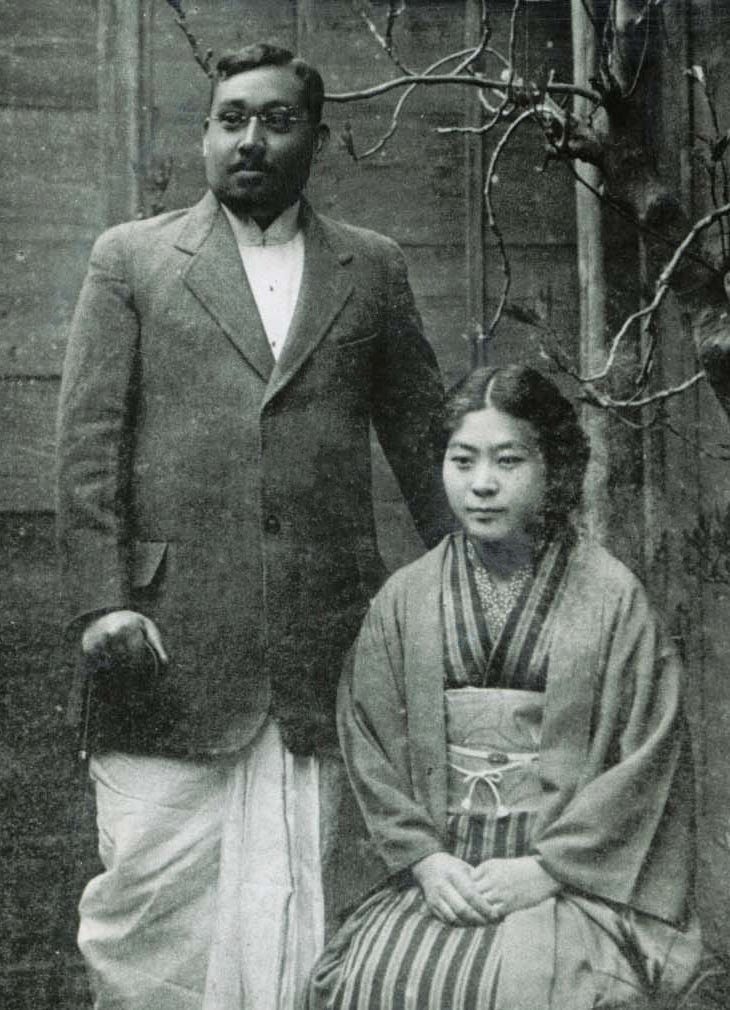

Rashbehari Bose was born in 1886 in the Hooghly district of Bengal, India. He ran away twice in his teens to join the British Indian Army. A “martial race policy” meant that only members of certain ethnic groups could enlist in the British army, which was terrible news for Bose. Bengalis were excluded because they were seen as unfit for combat. The British scorned Bose on both occasions, mocking him for being a Bengali. Infuriated by his rejection, Bose decided to show his military prowess as an adversary of the Empire.

On December 23, 1912, Bose snuck into a crowd gathered in Delhi to see the Viceroy of India, Charles Hardinge’s parade. He tossed a homemade bomb at the elephant on which Hardinge was sitting, wounding him and killing a servant.

Bose evaded arrest and wasn’t even a suspect in the case. He collaborated with the Ghadar Party, an organization of Indian expats in Canada and Britain that sought to abolish British control in India. Bose and the Ghadar Party were engaged in an armed revolution against the Empire. After the British began cracking down on Ghadar leaders, Bose forged his identity and escaped to Japan in 1915.

Japan, a British ally during the First World War, was willing to extradite Bose. However, large sections of Japanese society were sympathetic to India’s freedom struggle. Influential Japanese politician Mitsuru Toyama and a wealthy couple, Aizo and Kotsuko Soma, assisted Bose in avoiding arrest by the British.

For several months, the Somas hid Bose in their bakery, Nakamuraya. He became close to Toshiko, their daughter, who also served as his interpreter. Rashbehari Bose and Toshiko Soma were married in 1918, and the couple had two daughters.

While hiding from the British, Bose introduced the Soma family to Indian chicken curry. The dish impressed them with its distinct character and more robust flavor than a standard Japanese curry.

In 1925, tragedy struck Bose as Toshiko passed away from tuberculosis. But the daredevil revolutionary refused to be bogged down. He suggested that his father-in-law open a cafe. In 1927, the Nakamuraya cafe opened in Tokyo’s Shinjuku neighborhood, serving the chef’s signature “authentic Indian chicken curry.”

For Bose, chicken curry was more than just a meal to sell in Japan. It served as a cultural icon against British imperialism. Takeshi Nakajima writes in his book Bose of Nakamuraya (2009) that establishing the Indian curry style was part of Bose’s anti-colonial revolt. He wanted to reclaim curry from British hands because it was essential to Indian cuisine. Even today, the official tagline for Nakamuraya’s Indian-style curry is ‘The taste of love and revolution.”

Bose’s Indian curry was more expensive than the British-style curry because he sourced his ingredients from India and didn’t use European-style curry powder. People enjoyed the Indian curry so much that they were willing to pay more. Owing to the increased demand for Indian curry, Nakamuraya became one of the first food companies to be listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 1939.

Japan had embraced two distinct curry styles: British and Indian. But a problem had to be solved. The spices used in curries were imported, expensive, and unaffordable for most people.

Popularizing the Curry

Japan began producing curry powder during the Taisho period (1912–26). Minejiro Yamazaki, the founder of S&B Foods, introduced the first curry powder manufactured in Japan in 1923, packaged in its iconic red can. People now had an inexpensive way to make curry at home.

The dish’s iconic reputation was established after WWII with the introduction of the curry roux, which was inspired by chocolate packaging. In 1950, Bell Shokuhin Co., Ltd sold curry roux in chocolate-like blocks. A small roux cube included all the elements required to produce a curry; all you had to do was add water, meat, and vegetables.

The curry roux was a lifesaver for the Japanese people, who struggled to make time for home-cooked meals due to the rise of modern corporate culture. Convenience increased the curry’s popularity.

House Foods launched the “Vermont Curry” in 1963. It contained apples and honey, which added a sweet element to a normally spicy dish. The dish was called Vermont curry in honor of D.C. Jarvis, an American physician from Vermont, who promoted honeygar, a mix of apple cider vinegar and honey believed to have health benefits. Jarvis’s book, Folk Medicine: A Vermont Doctor’s Guide to Good Health, was popular in Japan in the 1960s.

Kids loved Vermont Curry, and curry was now popular among all age groups.

Over the years, different dishes involving curry, such as curry ramen, fried chicken curry, curry bread, curry udon, and my favorite, katsu curry, have become ubiquitous in Japan.

Besides the familiar curry dishes, regional varieties are growing in popularity in Japan. In Hokkaido prefecture, you get the Yezo deer curry (ezoshika karē), while scallop curry (hotate karē) is a specialty of the Aomori prefecture. Aomori and Nagano are also known for apple curry (ringo karē). Using fruits as a main ingredient of curry isn’t limited to apples; Shimane prefecture is famous for its nashi pear curry (nashi karē). Oyster curry (kaki karē) is common in Hiroshima, and Okinawa serves a unique bitter melon curry (gōyā karē).

Local diversities in curry are increasing thanks to innovative chefs and Japan’s embrace of newer varieties of the dish.

The story of curry in Japan is one of embracing fusion and tradition while striving to add a distinct local flavor. The dish reflects various historical events that shaped Japan’s history, such as the Meiji Restoration, contact with the British Navy, the introduction of potato farming, and India’s struggle for independence.

British and Indian-style curries found an audience in Japan as corporations and chefs continued experimenting, introducing new dishes and ways of consuming curry. Karē raisu (curry and rice) evolved to suit the Japanese palate, and local twists on the traditional curry emerged nationwide.

Japanese curry has cemented itself in the UK’s culinary scene, with restaurants serving traditional Japanese curries and grocery stores stocking the curry roux. Other countries are also welcoming Japanese curry.

CoCo Ichibanya and Go! Go! Curry, Japan’s top curry restaurant chain, has expanded operations with outlets in China, the US, Canada, Vietnam, India, South Korea, Indonesia, and Thailand. This is a positive development compared to a decade ago, when I had katsu curry for the first time in Washington, D.C., and only a few restaurants offered it.

Soon, curry could join sushi and ramen as one of the most globally recognized Japanese dishes.

History influences our food. If you enjoyed how past events shaped the Japanese curry, check out other stories from humanity’s culinary past here.

Do you love exploring the mysteries of lost civilizations and the rich cultures of the ancient world?

Share this story with friends and family, and don’t forget to subscribe to this newsletter for more fascinating insights!

If you enjoyed this story and would love to read more such write-ups, please upgrade to a paid membership.

References

Japanese Curry: How a British Navy staple inspired one of Japan’s most beloved dishes, Public History Amsterdam.

Rash Behari Bose: A ‘Revolutionary Chef,’ Peepul Tree Stories

The Real Story of Curry, Food and Wine.

William S. Clark: Legend in Japan, Nearly Forgotten in Massachusetts, Historical Digression.

Connigham Lizzie (2005), Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, Oxford University Press.T

Growing up in Delhi, the only curry I knew was egg currry-- which isn't really an Indian dish but probably Anglo-Indian.

In fact, I got confused when I went aboard (Brazil) and people asked me about curry.

Fascinating! I love learning about how foods assimilate and travel. My mom’s family were very culturally British Americans so she would always make this dish, Captains Chicken, which was like a tomato stew with chicken and currants and curry spice. I don’t know the history but I’ve always figured it has its roots in British colonial India, in a way probably similar to Japanese curry