In 612 BC, the Babylonians and Medes, tired of being subjugated by the Assyrians, joined forces to attack Nineveh, the capital of Assyria. The chief scribe witnessed the devastation as the invaders approached him up the hill. The library was destroyed in flames, and Nineveh was buried in the sands of time until British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard began excavating the ruins of the once-great metropolis in the 1850s.

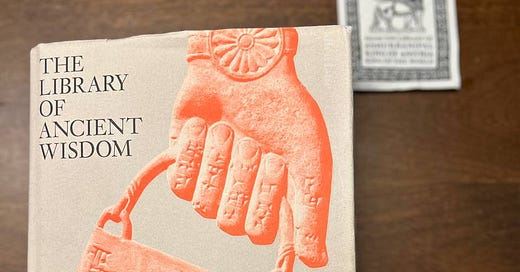

Among his most famous finds was the Library of Ashurbanipal, the subject of Selena Wisnom's engrossing work in her debut book, The Library of Ancient Wisdom: Mesopotamia and the Making of History. His library had over 30,000 tablets, making it the largest in the ancient world before the Library of Alexandria.

Long-time readers of Forgotten Footprints are familiar with the Assyrians and the Library of Ashurbanipal. If you need a refresher, check out the following story.

Unlike the Library of Alexandria, which was lost forever, something remarkable occurred in Nineveh's library. As the fires spread, the clay tablets containing the knowledge were baked, transforming Ashurbanipal's Library into a furnace and preserving them forever. As a result, archaeologists have discovered some original masterpieces as well as fragments of others, allowing us to reconstruct what ancient Assyria valued.

Selena Wisnom's work expertly recreates the world of ancient Mesopotamia for the contemporary reader. She resurrects Ashurbanipal's Library, allowing us to stroll through its halls and witness the genesis of systematic knowledge.

In this review, I’ll discuss why this book stands out as a monumental scholarly work. Yet, it has a profoundly human narrative, where the author makes a strong case for why the library was a significant milestone in the development of how we store and apply knowledge to solve daily problems.

Let us dive in.

Reminder: By choosing a paid membership (just $5 a month or $50 annually), you're helping amplify voices that history books too often overlook. Your support means these stories get the attention they deserve.

You’ll gain access to tons of members-only content👇

Full-length deep dives into untold stories: no paywalls, no cuts.

The entire archive of amazing stories from the Ice Age to the Fall of the Mongol Empire, the hottest archaeological finds, and the appetizing history of food.

Early access to special editions—be the first to dive in.

Join lively discussions in members-only posts and subscriber chats.

The Art of Writing

In a world where we are bombarded with AI-generated content, especially written, I appreciate the author’s efforts in reminding us that writing was an art in ancient Assyria. The mistakes Libbali-sharrat, Ashurbanipal’s queen, made while writing, along with her poor handwriting being the subject of ire among the king’s sisters, tell us how significant writing was in the Assyrian court.

We learn about the origins of Proto-cuneiform and cuneiform from the earliest tables found in Uruk, dating to the fifth millennium BC, to the development of writing in Assyria. The influence of cuneiform was widespread in the Fertile Crescent, as the Hittites and the city-states of the Levant, such as Ugarit, adopted it as their primary script.

One of the things that stood out was the highlighting of how Assyrian scholars believed that the signs and sounds in their writing system had a fundamental connection to the universe.

Wisnom says:

If one sign sounded similar to another, or looked like another, this was not merely coincidence but an insight into nature of reality itself, which was constructed through language. Puns became an important tool for interpreting difficult texts, and a serious object of study.

We typically don’t connect signs, sounds, and puns with the universe, but it is fascinating to see that ancient Assyrian scholars believed writing had a divine purpose.

In my post about Ashurbanipal’s quest for knowledge, I highlighted how the king was encouraged by his father to learn reading and writing from a young age. Wisnom examines the literary career and academic training of the ruler in detail, revealing why the fearsome conqueror valued knowledge above all else.

The author adopts a thematic approach to history. After providing a clear picture of the development of writing in ancient Mesopotamia, she proceeds to explain the various subjects addressed in the library.

Witchcraft, Lamentations, Magic, and Literature

We can group the library’s collection into two types of texts.

The first category was legal and administrative documents. The second category comprised literary works, holy texts, medicinal, mathematical, and mythological works. The author has primarily focused on the second category.

A common theme that emerges among all the subjects is the intimate connection between people's lives and the world of the gods. There was no distinction between the divine and the mortal. It was a part of a natural order.

Wisnom says:

Belief was not a choice; the gods were just a part of the world that everyone took for granted. It would be like asking whether we believed in the sun.

Gods played a vital part in people’s lives, and decisions made by rulers were often based on how the supernatural forces would perceive them.

The magic and witchcraft section was quite fascinating, especially the role of women in court politics and how they interacted with exorcists to influence statecraft. Notably, the role of Naqia, Esharhaddon’s mother, in interacting with the oracle of Ishtar of Arbela was intriguing. Eshadhaddon was Ashurbanipal’s father.

In the modern scientific world, we have a negative perception towards magic and extispicy, the practice of divination by examining the entrails of sacrificed animals. However, in ancient Assyria, there was a harmonious coexistence of magicians, diviners, exorcists, and medical professionals, who consulted with each other to assist the king.

The idea of magic was always to get the gods on the side of the petitioner. Elaborate rituals existed to ensure that prayers were taken seriously. Wisnom says magic was a way for the Assyrians to cope with their difficulties, and was society’s way of addressing people’s concerns.

I enjoyed the representation of various subjects such as magic, exorcism, witchcraft, and soothsaying in a non-judgmental manner, while sensitizing the reader to a world where people’s solutions to concerns we have were different.

Of course, no discussion about ancient Mesopotamia is complete without a mention of the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The Epic of Gilgamesh tells the story of Gilgamesh, the legendary king of Uruk. It revolves around his friendship with Enkidu, a part-animal, part-human creation whom the gods send to control Gilgamesh. The story inspired many popular tales and influenced later literary works, such as the Bible and the Iliad. The Epic of Gilgamesh is the first scholarly work to mention the Great Flood, a story later recounted in the Bible.

The author provides a detailed account of Gilgamesh’s life and the evolution of his character. She also focuses on the role of women in the legendary king’s life journey and says that women significantly affected the course of the story.

Would Gilgamesh’s life have turned out the way it did had he not met Enkidu? Yet it was a priestess, Shamhat, who tames and brings him to Uruk. Gilgamesh sets off on a journey to attain immortality, seeking the plant of life, and it is Utnapishtim’s (mentioned as Ut-napishti in the book) wife who advises him to do so. Utnapishtim was the legendary king of Shuruppak, who survived the Great Flood by building a boat, a character similar to Noah.

Women had many rights in ancient Assyria, including the right to divorce, own property, and run businesses despite the society being patriarchal. It is pretty interesting to learn that in literature, too, there were prominent female characters.

Final Thoughts

What distinguishes Wisnom's approach is her ability to combine archeological rigor with narrative flair. She smoothly combines scholarship and a knack for storytelling. A complex and rarely discussed subject is made accessible and relevant.

When she describes the library's contents, which range from astronomical charts to medicinal texts, she recreates the intellectual ecosystem in which the Assyrians lived and how it influenced their lives.

The book primarily focuses on the lives of the Assyrian aristocracy and their relationship with the divine. There is less emphasis on the lives of ordinary people. I would have loved to know more about ancient Mesopotamian daily life, which may have been documented through mundane records and tax receipts.

I would strongly recommend this book for anyone interested in ancient history in general. However, if you, like me, enjoy learning about Mesopotamian cultures, you will adore this book.

This is not a fast-paced page-turner.

Expect an ambling luxury tour of the power corridors of Assyria, as you unwind on a peaceful Sunday afternoon to learn about the Library of Ancient Wisdom.

Do you love exploring the mysteries of lost civilizations and the rich cultures of the ancient world?

Share this story with friends and family, and don’t forget to subscribe to this newsletter for more fascinating insights!

If you enjoyed this story and would love to read more such stories, please upgrade to a paid membership.

WOW, this LIBRARY OF ANCIENT WISDOM goes onto my MUST READ list. Thank you!

For more on this topic covering a wider time and cultural span:

LIBRARIES IN THE ANCIENT WORLD by Lionel Casson (Yale University Press, 2001), paperback

https://www.amazon.com/Libraries-Ancient-World-Lionel-Casson/dp/0300097212/ref=sr_1_1

Would love to read this book .